The Pacific is in vogue. After years of attracting little but scholarly attention, the Pacific Theater of the Second World War has captured the popular imagination in a string of books, feature films and an Emmy-award winning television series, aptly called “The Pacific” and written in part by University of Texas and Plan II graduate Robert Schenkkan. Now comes best-selling author Laura Hillenbrand with a new best seller, Unbroken: A World War II Story of Survival, Resilience, and Redemption.

Unbroken tells the story of Olympic runner Louis Zamperini’s ordeal as a Japanese prisoner of war. Captured in 1943 when his B-24, The Green Hornet, crashed in the South Pacific, Zamperini spent a then-record 47 days on a battered rubber raft in storm-tossed, shark-infested waters with two comrades, only to be plucked from the edge of extinction by a Japanese patrol boat and sent to the infamous Omori POW camp on an artificial island in Tokyo Bay. Starved, beaten, and denied medical attention, Zamperini became the target of a sadistic guard nicknamed “The Bird.” The Bird was no tropical nestling but a vulture feeding off the pain of his helpless captives.

Miraculously, Zamperini survived. After months of recuperation, he returned to the embrace of his Italian-American family, married a debutante and, like many veterans, kept his story to himself. He devoted his days to regaining the athletic form that once made him a running prodigy but failed to win it back and spiraled into a well of depression and alcoholism. The saving grace of his faith, ignited by a fledgling evangelist named Billy Graham, sent him on a mission to spread the good news of the Christian Gospel and save others, among them young souls at risk of delinquency. That task suited Zamperini who had been something of a bad boy himself before the discipline of the track turned him from a would-be criminal into an Olympic competitor. Robust even in old age, draped in accolades, he rode skateboards, flew planes, carried an Olympic torch, and told of his ordeal in the Pacific to those in search of inspiration. In time, a reborn Zamperini returned to Japan and forgave his captors.

Hillenbrand has written a riveting tale of a terrible episode from a time when 132,000 Allied POWs, Americans but also British, Australian, Canadian and others, suffered unspeakable misery at the hands of the Japanese. More than one in four of them died. Their collective story has been told before, most notably in Gavan Daws’s Prisoners of the Japanese: POWs in World War II in the Pacific and Michael and Elizabeth Norman’s Tears of Darkness: The Story of the Bataan Death March and Its Aftermath. Instead, Hillenbrand gives us a single life depicted with verve and complexity.

In Hillenbrand’s deft hands, Louis Zamperini is all too human and so are some of his captors. The Japanese emerge not as a single type, cut only from the predictable cloth of the sadist Bird, but as men who behave in ways that complicate and at times contradict the cliché. To be sure, most are merciless, but a few are respectful and one even compassionate. Frequent digressions—on the development of the Norden bombsight, the Japanese code of Bushido, the psychology of prison guards, the fate of former Pacific POWs (who lost an average of 61 pounds and later died at a rate four times faster than other men their age)—put historical meat on Zamperini’s bones. The bulk of Hillenbrand’s prodigious research in the salient secondary sources and some key archival ones rests on hours of interviews with Zamperini and others. The outcome is a popular history with weight and mass.

What is missing for historians is the larger context of the story and the historiographical framework within which Zamperini’s experience unfolds. What does his story or the story of any Pacific POW mean beyond being a narrative of “survival, resilience, and redemption”? How much do Zamperini’s experiences reflect change and continuity over time for cultures and captives in other wars? For Japan in this war? For the United States? To answer those and other historically minded questions, readers can turn to the growing body of literature that is shifting our attention from the war in Europe to the war in Asia and the Pacific (listed below in the recommended reading). To criticize Hillenbrand for these omissions is to pick apart a book she did not intend to write. She chose to tell a different tale and does so masterfully. Historians might learn a thing or two about storytelling from reading it.

The Pacific is very much in vogue as what some have called “The Greatest Generation” passes from our midst, and Asia and the Pacific Rim grow in contemporary importance. Such a vogue serves as a welcome corrective to the Eurocentric view of the Second World War too often seen in the West. With the best-selling Unbroken, Laura Hillenbrand brings a small but important part of the Pacific War to a popular audience in the fascinating story of a man who rose to Olympic heights, fell beneath the contempt of his captors, and found his purpose in a life both human and heroic. More power to her, for any book that spreads the good news of history written as well as Hillenbrand’s is good news indeed.

Related Reading:

Saburo Ienaga, The Pacific War, 1931-1945 (English translation, 1978)

John Dower, War Without Mercy: Race and Power in the Pacific War (1987)

Gavan Daws, Prisoners of the Japanese: POWs in World War II in the Pacific (1996)

Michael Norman and Elizabeth M. Norman, Tears of Darkness: The Story of the Bataan Death March and Its Aftermath (2009)

Related Viewing:

Flags of Our Fathers (d. Clint Eastwood, 2006)

Letters from Iwo Jima (d. Clint Eastwood, 2006)

City of Life and Death (d. Lu Chuan, 2009)

The Pacific (d. Tim Van Patten et al., 2010)

by

by

New ideas flourished and the emergence of Arab nationalism is often attributed to this time and place.

New ideas flourished and the emergence of Arab nationalism is often attributed to this time and place.

Rejecting the oft-repeated assertion that U.S. foreign policymakers were ignorant or inattentive to the realities of power in the Soviet Union and the complexities of Third World nationalism, Leffler argues that cold warriors on both sides of the iron curtain were in fact keenly aware of the liabilities inherent in the zero-sum approach to international politics. Benefiting from access to multiple archives and a clear command of the secondary historical literature, Leffler has crafted a persuasive and thoroughly documented analysis that recasts the Cold War as not simply a political, economic, or military confrontation, but a battle “for the soul of mankind.” In doing so, he has transcended the scholarly debate over whether economic, structural, or ideological factors were more influential in determining the course of Cold War history.

Rejecting the oft-repeated assertion that U.S. foreign policymakers were ignorant or inattentive to the realities of power in the Soviet Union and the complexities of Third World nationalism, Leffler argues that cold warriors on both sides of the iron curtain were in fact keenly aware of the liabilities inherent in the zero-sum approach to international politics. Benefiting from access to multiple archives and a clear command of the secondary historical literature, Leffler has crafted a persuasive and thoroughly documented analysis that recasts the Cold War as not simply a political, economic, or military confrontation, but a battle “for the soul of mankind.” In doing so, he has transcended the scholarly debate over whether economic, structural, or ideological factors were more influential in determining the course of Cold War history.

by

by

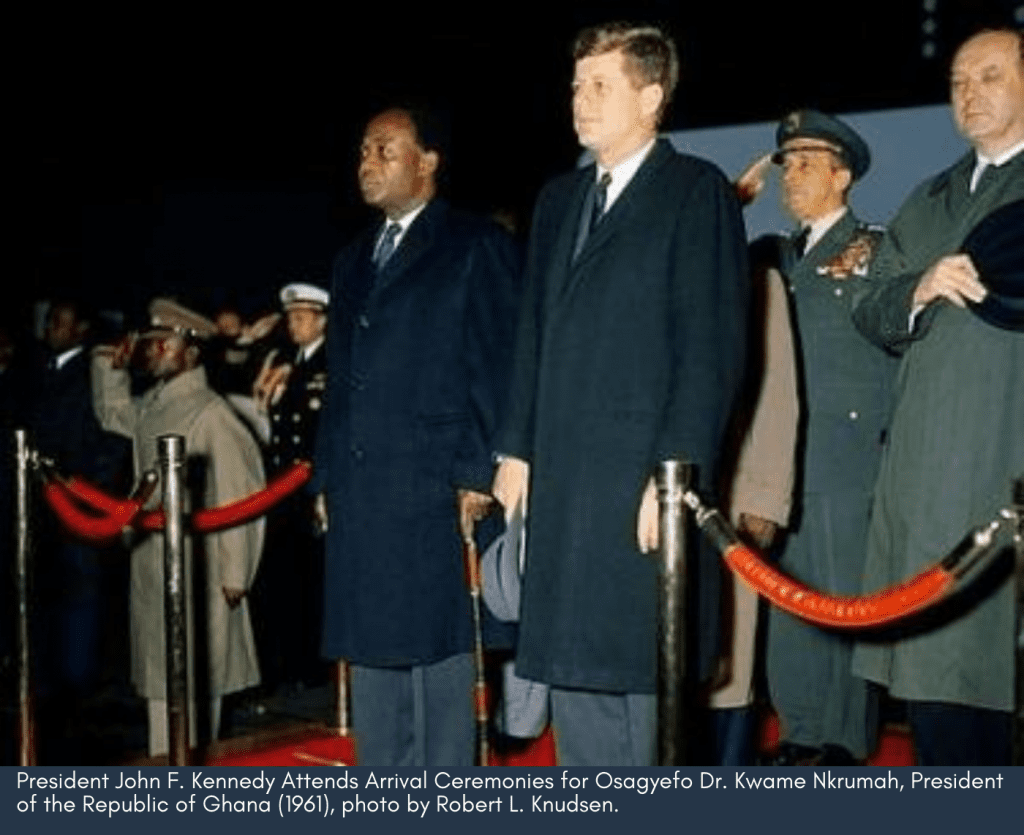

His references to Gandhi and the fall of the Berlin Wall evoked powerful images for most Americans, but Obama’s allusion to the small West African nation of Ghana may be less familiar. Yet in 1957, Ghana’s peaceful transition to independence heralded the end of European colonialism and served as an inspiration to oppressed peoples throughout the world. Kevin Gaines’ American Africans in Ghana recovers the symbolic role that the young nation played in the African American freedom struggle, and the reasons why it stirred

His references to Gandhi and the fall of the Berlin Wall evoked powerful images for most Americans, but Obama’s allusion to the small West African nation of Ghana may be less familiar. Yet in 1957, Ghana’s peaceful transition to independence heralded the end of European colonialism and served as an inspiration to oppressed peoples throughout the world. Kevin Gaines’ American Africans in Ghana recovers the symbolic role that the young nation played in the African American freedom struggle, and the reasons why it stirred