Fifteen years ago, Alexander Street Press, in conjunction with the Center for the Historical Study of Women and Gender at the State University of New York, Binghamton, launched Women and Social Movements in the United States, 1600 – 2000, an online database edited by historians Kathryn Kish Sklar and Thomas Dublin. What began as a classroom project designed by Sklar to give undergraduate students the opportunity to collect, edit, analyze – and get excited about – historical documents, went live in December 1997 after being developed into a full-blown documentary database by Sklar and Dublin.

Newly enfranchised women registering to vote, Seattle c.1910 (Wikimedia commons)

Newly enfranchised women registering to vote, Seattle c.1910 (Wikimedia commons)

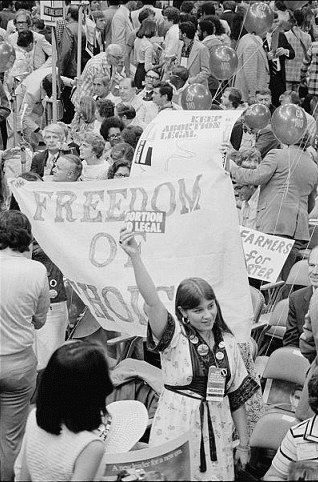

The “Documentary Projects,” in particular, will interest Not Even Past readers. Scholars pose a historical question, write an introduction with background information, and offer up a set of documents. In How Did African American Women Shape the Civil Rights Movement and What Challenges Did They Face?, created by Gail S. Murray, a December 1963 letter from Septima Clark to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. conveys Clark’s critique of members of the Southern Christian Leadership Council, King’s organization, for being more interested in the “glamor” of direct action movements (involving civil disobedience and news headlines), than the day-to-day work of voter education that she believes will bring lasting change to the region. And in Judith N. McArthur’s How Did Texas Women Win Partial Suffrage in a One-Party Southern State in 1918?, correspondence offers evidence of how a group of savvy Texas suffragists negotiated the specific historical context of World War I, Prohibition, and the election of Governor Hobby to procure the vote in advance of the federal 19th Amendment, at least for American-born white women.

I love this database. It allows me to introduce students to primary sources, and allows them to get their feet wet in historical research and encourage them to come up with their own interpretations of documents. In the “Scholar’s Edition” (available through university libraries by subscription), the primary sources are organized by movement, so one can explore controversies related to such topics as the birth control movement, women’s suffrage, anti-lynching campaigns, and union organizing by immigrant women. The “Scholar’s Editon” site also includes a full run of issues of The Ladder: A Lesbian Review (1956-1972) and papers of the civil liberties exponent Elizabeth Glendower Evans, who championed the cause of Sacco and Vanzetti.

WASM has grown exponentially since 1997, adding thousands of new documents a year and growing such features as a book review section, outlines for classroom projects based on the documents, and a monthly online journal that combines standard fare of academic journals with new documentary projects and full-text documents. As has been true with most projects documenting women’s history, Sklar and Dublin’s venture has resembled a social movement in itself; they sought out scholars, wrote emails and hosted conference luncheons not only to publicize the site but to convince scholars of women and social movements to place on line a set of documents they have used in their research. They now have new horizons. Alexander Street Press has just launched Women and Social Movements – International.

WASM has grown exponentially since 1997, adding thousands of new documents a year and growing such features as a book review section, outlines for classroom projects based on the documents, and a monthly online journal that combines standard fare of academic journals with new documentary projects and full-text documents. As has been true with most projects documenting women’s history, Sklar and Dublin’s venture has resembled a social movement in itself; they sought out scholars, wrote emails and hosted conference luncheons not only to publicize the site but to convince scholars of women and social movements to place on line a set of documents they have used in their research. They now have new horizons. Alexander Street Press has just launched Women and Social Movements – International.

Photo credits:

Warren K. Leffler, “Crowds surrounding the Reflecting Pool, during the 1963 March on Washington,” 28 August, 1963

U.S. News and World Report via The Library of Congress

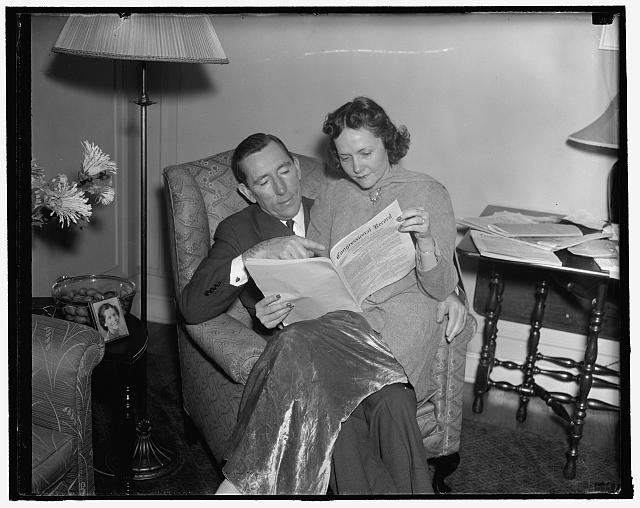

Harris & Ewing, “No rest for a weary filibuster. Washington, D.C., Jan. 27. Senator Claude A. Pepper, Democrat of Florida who spoke for 11 hours during the current filibuster against the Anti-lynching bill, points out to pretty Mrs. Pepper the interesting sections of his long winded talk as he printed in the Congressional Record,” Washington, DC, 27 January 1938

Harris & Ewing via The Library of Congress

Tips on How to Navigate the Women and Social Movements Website

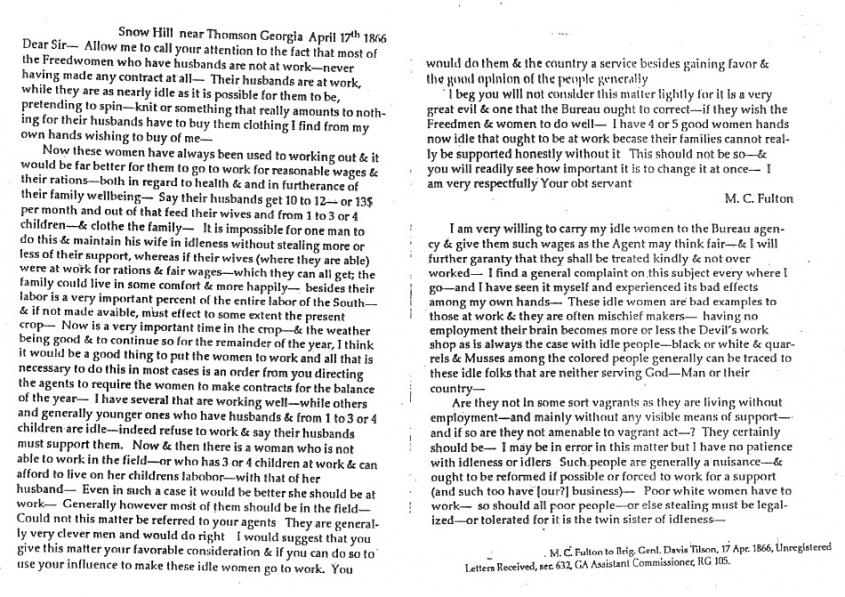

The “Articles for Immoral Use” were devices and potions for contraception or abortion. Commonly called the

The “Articles for Immoral Use” were devices and potions for contraception or abortion. Commonly called the