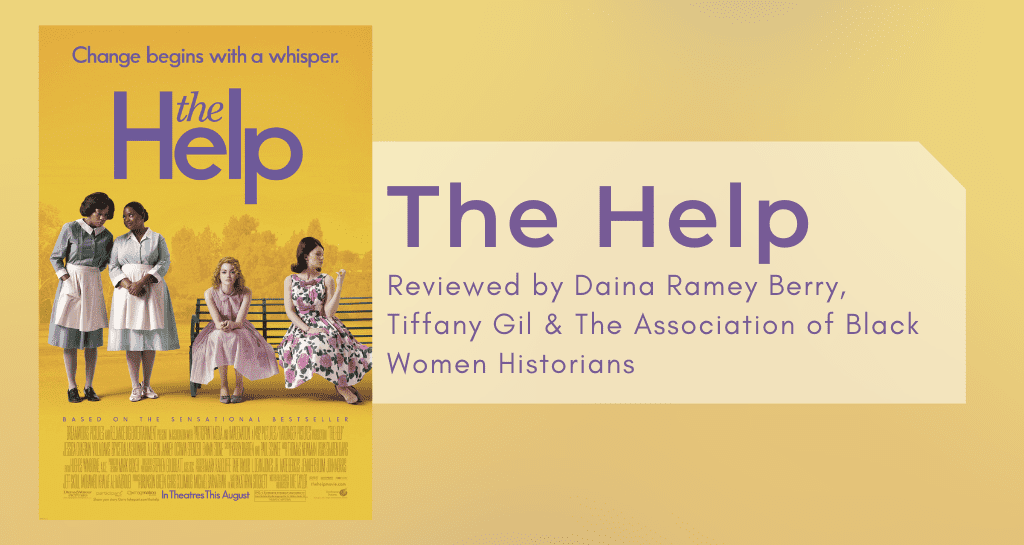

By Daina Ramey Berry, Tiffany Gill, and the Association of Black Women Historians

Historical films and books always distort the historical record for dramatic purposes. Sometimes that doesn’t matter and sometimes it does. The Help, a best-selling book and now a film playing nationwide, elicited this statement from the Association of Black Women Historians.

On behalf of the Association of Black Women Historians (ABWH), this statement provides historical context to address widespread stereotyping presented in both the film and novel version of The Help. The book has sold over three million copies, and heavy promotion of the movie will ensure its success at the box office. Despite efforts to market the book and the film as a progressive story of triumph over racial injustice, The Help distorts, ignores, and trivializes the experiences of black domestic workers. We are specifically concerned about the representations of black life and the lack of attention given to sexual harassment and civil rights activism.

During the 1960s, the era covered in The Help, legal segregation and economic inequalities limited black women’s employment opportunities. Up to 90 per cent of working black women in the South labored as domestic servants in white homes. The Help’s representation of these women is a disappointing resurrection of Mammy—a mythical stereotype of black women who were compelled, either by slavery or segregation, to serve white families. Portrayed as asexual, loyal, and contented caretakers of whites, the caricature of Mammy allowed mainstream America to ignore the systemic racism that bound black women to back-breaking, low paying jobs where employers routinely exploited them. The popularity of this most recent iteration is troubling because it reveals a contemporary nostalgia for the days when a black woman could only hope to clean the White House rather than reside in it.

Both versions of The Help also misrepresent African American speech and culture. Set in the South, the appropriate regional accent gives way to a child-like, over-exaggerated “black” dialect. In the film, for example, the primary character, Aibileen, reassures a young white child that, “You is smat, you is kind, you is important.” In the book, black women refer to the Lord as the “Law,” an irreverent depiction of black vernacular. For centuries, black women and men have drawn strength from their community institutions. The black family, in particular provided support and the validation of personhood necessary to stand against adversity. We do not recognize the black community described in The Help where most of the black male characters are depicted as drunkards, abusive, or absent. Such distorted images are misleading and do not represent the historical realities of black masculinity and manhood.

Furthermore, African American domestic workers often suffered sexual harassment as well as physical and verbal abuse in the homes of white employers. For example, a recently discovered letter written by Civil Rights activist Rosa Parks indicates that she, like many black domestic workers, lived under the threat and sometimes reality of sexual assault. The film, on the other hand, makes light of black women’s fears and vulnerabilities turning them into moments of comic relief.

Similarly, the film is woefully silent on the rich and vibrant history of black Civil Rights activists in Mississippi. Granted, the assassination of Medgar Evers, the first Mississippi based field secretary of the NAACP, gets some attention. However, Evers’ assassination sends Jackson’s black community frantically scurrying into the streets in utter chaos and disorganized confusion—a far cry from the courage demonstrated by the black men and women who continued his fight. Portraying the most dangerous racists in 1960s Mississippi as a group of attractive, well dressed, society women, while ignoring the reign of terror perpetuated by the Ku Klux Klan and the White Citizens Council, limits racial injustice to individual acts of meanness.

We respect the stellar performances of the African American actresses in this film. Indeed, this statement is in no way a criticism of their talent. It is, however, an attempt to provide context for this popular rendition of black life in the Jim Crow South. In the end, The Help is not a story about the millions of hardworking and dignified black women who labored in white homes to support their families and communities. Rather, it is the coming-of-age story of a white protagonist, who uses myths about the lives of black women to make sense of her own. The Association of Black Women Historians finds it unacceptable for either this book or this film to strip black women’s lives of historical accuracy for the sake of entertainment.

Ida E. Jones, National Director of ABWH and Assistant Curator at Howard University.

Daina Ramey Berry, Tiffany M. Gill, and Kali Nicole Gross, Lifetime Members of ABWH and Associate Professors at the University of Texas at Austin.

Janice Sumler-Edmond, Lifetime Member of ABWH, Professor at Huston-Tillotson University.

Any questions, comments, or interview requests can be sent to:

ABWHTheHelp@gmail.com

Suggested Reading:

Fiction:

Like one of the Family: Conversations from A Domestic’s Life by Alice Childress

The Book of the Night Women by Marlon James

Blanche on the Lam by Barbara Neeley

The Street by Ann Petry

A Million Nightingales by Susan Straight

Non-Fiction:

Out of the House of Bondage: The Transformation of the Plantation Household by Thavolia Glymph

To Joy My Freedom: Southern Black Women’s Lives and Labors by Tera Hunter

Labor of Love Labor of Sorrow: Black Women, Work, and the Family, from Slavery to the Present by Jacqueline Jones

Living In, Living Out: African American Domestics and the Great Migration by Elizabeth Clark-Lewis

Coming of Age in Mississippi by Anne Moody

Related articles on Not Even Past:

Tiffany Gill on African American women and beauty shop politics

Daina Ramey Berry on former slave narratives

Matt Tribbe on Raymond Arsenault’s Freedom Riders

Photo Credits:

“Beaumont, Texas. Mrs Elsie McMullen, a laundry truck driver returning home from work. A maid takes care of her children during the day.” Library of Congress

“Washington, D.C. Negro maid inthe home of a government worker.” Library of Congress

By

By

By

By

A few years ago, after discussing the origins and consequences of the

A few years ago, after discussing the origins and consequences of the