In 1873, the US Congress passed an “Act for the Suppression of Trade in, and Circulation of, Obscene Literature and Articles for Immoral Use.”  The “Articles for Immoral Use” were devices and potions for contraception or abortion. Commonly called the Comstock Law after Anthony Comstock, one of the founders of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice and a major proponent of the legislation, by 1900, over twenty states including Connecticut had state “Comstock Laws” that made the distribution of birth control illegal. It was decades before birth control was fully decriminalized. When, in 1965, Justice William O. Douglas wrote the majority decision in Griswold v. Connecticut, he identified a “right of privacy” implicit in the Fourth Amendment that guaranteed the right of couples to receive birth control information, devices, or prescriptions from physicians. After subsequent decisions extended this right to non-married people, a woman’s right to prevent pregnancy seemed secure. Since birth control is in the news again, a look at one of the best histories of the birth control movement in the U.S. is timely.

The “Articles for Immoral Use” were devices and potions for contraception or abortion. Commonly called the Comstock Law after Anthony Comstock, one of the founders of the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice and a major proponent of the legislation, by 1900, over twenty states including Connecticut had state “Comstock Laws” that made the distribution of birth control illegal. It was decades before birth control was fully decriminalized. When, in 1965, Justice William O. Douglas wrote the majority decision in Griswold v. Connecticut, he identified a “right of privacy” implicit in the Fourth Amendment that guaranteed the right of couples to receive birth control information, devices, or prescriptions from physicians. After subsequent decisions extended this right to non-married people, a woman’s right to prevent pregnancy seemed secure. Since birth control is in the news again, a look at one of the best histories of the birth control movement in the U.S. is timely.

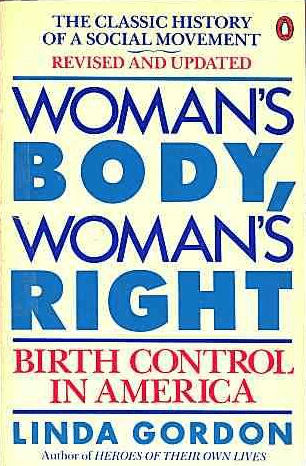

Linda Gordon, the Florence Kelley Professor of History at New York University, published Woman’s Body, Woman’s Right: Birth Control in America in 1976. In 2002, she published a revised and updated version of that book under a new title: The Moral Property of Women: A History of Birth Control Politics in America. Gordon’s analysis of the history of birth control politics is not an uncritical tale of the heroic triumph of birth control advocates. Her central argument is that crusades for reproductive rights must be evaluated in their particular political context: “Reproduction control brings into play not only the gender system but also the race and class system, the structure of medicine and prescription drug development and reproduction, the welfare system, the education system, foreign aid, and the question of gay rights and minors’ rights.” Gordon’s account is a multi-dimensional exploration.

She begins with a discussion of Victorian sexual ideology and the work of late-nineteenth century birth control entrepreneurs. She then traces a complex history of birth control movements to demonstrate that “neo-Malthusianism, voluntary motherhood, Planned Parenthood, race suicide, birth control, population control, control over one’s own body,… were not merely different slogans for the same thing but helped construct different activities, purposes, and meanings.” The campaign for legal access to birth control included individuals and organizations with diverse and often contradictory goals.

Gordon explains that early twentieth-century “birth controllers” were radical reformers—feminists, socialists, and liberals—who hoped to aid the working class in their struggle with capitalism by helping women limit family size. Birth control pioneer Margaret Sanger initially found support for birth control among socialists and sex radicals but by 1915, she abandoned socialist organizing and focused on the single issue of birth control. Gordon analyzes the work of Sanger’s first birth control clinic in New York City, her creation of the American Birth Control League, her civil disobedience, her strategic cultivation of moneyed and influential allies, her attraction to eugenic arguments for birth control, her effective consolidation of once-rival organizations in 1938 into the Birth Control Federation of America, and that organization’s emergence as the Planned Parenthood Federation of America (PPFA) in 1942. But Sanger’s work is not the only narrative that Gordon provides. Gordon’s account of the birth control movement includes nuanced discussions of how the medical profession, the New Deal, the Roman Catholic Church, and the social conservatism of the 1940s and 1950s influenced birth control politics. For example, the PPFA and the medicalization of birth control brought needed attention to women’s health. At the same time, in its first two decades, the PPFA projected a defense of traditional marriage and, too often, “isolate[d] sexual and reproductive problems from women’s overall subordination.”

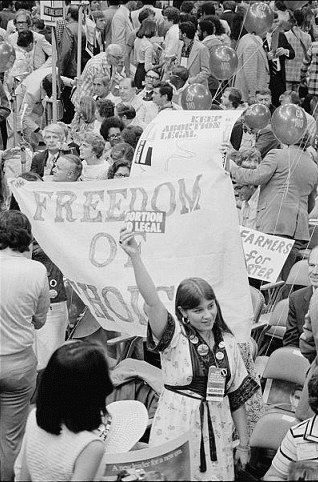

Gordon’s treatment of birth control politics and the larger issue of reproductive rights in the last half of the twentieth century lacks the comprehensive and critical attention that she provides for the late 19th century through the early 1960s. She briefly traces the abortion rights movement and the rise of antiabortion activism. She concludes this chapter presciently when she writes that “No one issue dramatizes the basic cultural/political fissures in the United States at this time more than abortion does—although there is competition from gay rights, gun control, and religion in the schools.”

Gordon writes about the Women’s Health Movement and notes that it positively influenced gynecological practice. She also writes about problems with the first generation of oral contraceptives, the notorious Dalkon Shield IUD, the salutary changes among “population control” advocates, and the scandal of sterilization abuse among women of color. Gordon suspects a racial subtext to the 1980s alarm about the rising rate of teenage pregnancies; and she makes the commonsense observation that while the U.S. has a higher teenage pregnancy rate than twenty-seven other industrialized countries, it is also the case that U.S. teenagers are less likely to use contraception that those in comparable countries.

She notes, but does not investigate, the conflicts between women’s rights activists. Mainstream, white and middle-class feminists were slow to recognize the particular concerns of women of color—concerns about forced sterilization, the availability of pre-natal care, and the persistent racism that motivated some birth control activists. In addition, Black Nationalists condemned birth control as a genocidal plot. Black women who hoped for a larger understanding of reproductive rights as well as access to birth control and abortion struggled both within their communities and with white women’s organizations. Gordon’s comprehensive and astute analysis of the first many decades of birth control advocacy encourage the reader to want more of the same about the last several decades. Still, Gordon’s book remains a superb examination of birth control politics.

Photo credit:

Unknown photographer, “Ms. Margaret Sanger,”

Bains News Service via The Library of Congress

Warren K. Leffler, “Demonstration protesting anti-abortion candidate Ellen McCormack at the Democratic National Convention, New York City,” 14 July 1976

Photographer’s own via The Library of Congress

You may also like:

Harvard University Professor of History Jill Lepore’s article on Planned Parenthood in a November 2011 issue of The New Yorker.

Like Smith,

Like Smith,