by Douglas Cushing

Francesca Consagra, curator of In the Company of Cats and Dogs at the Blanton Museum of Art, has observed that felines and canines in art are rarely mere props. More than decoration, their presence serves a meaningful purpose. These creatures may represent human endeavors, moralities, values, and behaviors. Alternately, their image may signify the lives and conditions of individual animals themselves, or entire categories of such animals, existing in domestic relationships with humans, as suppliers of labor, or even as a sources of food. Animals in art offer novel and useful ways to understand historical trends and events. Within this exhibition, an excellent example of how cats provide charged and multifaceted meanings in a work of art, is a hand-colored, soft-ground etching by James Gillray entitled The Injured Count, S. __ (c. 1786).

James Gillray, The Injured Count S. ____, (c. 1786). Hand-colored soft-ground etching. Blanton Museum of Art (used with permission).

The print depicts the buxom Countess of Strathmore, Mary Eleanor Bowes, blithely suckling two greedy cats as she drinks wine or liquor with a pockmarked companion. A child at her side bawls, “I wish I was a cat / my mama would love me then.” Despite its curious scenario, the print reflects the tendency towards pet keeping that emerged in Enlightenment England. It also points to the Western historical-symbolic relationship between femininity and felinity, the status of women in late eighteenth-century England, and the machinations of power that played out in arenas of class and gender.

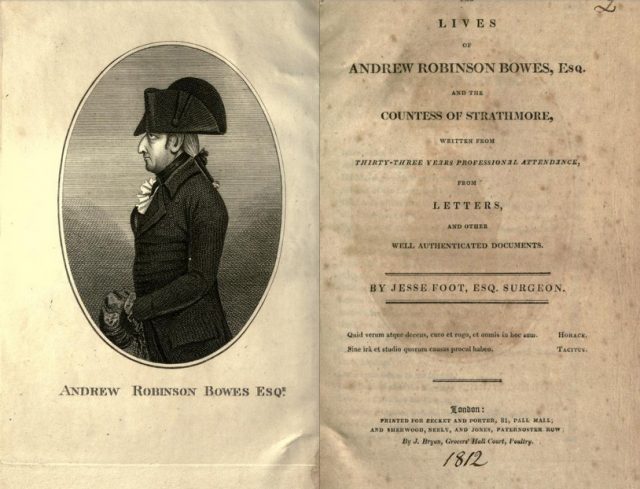

Gillray was a satirist working in a field that frequently burlesqued Georgian women, especially prominent ones.. The last four decades of the eighteenth century, when he was at work, are frequently thought to be the high point of English satirical printmaking. Here, the artist—something of a hired gun in the day—was likely fulfilling a commission that joined a series of attacks leveled against the countess. At the far left margin of the print, Gillray depicts her forsaken husband, Andrew Robinson Stoney, surveying a map of the countess’s estate. Stoney later changed his surname to Bowes, fulfilling the wishes of his wife’s father as expressed in his will. This name change traded the military associations with his family name for the more politically and socially recognized Bowes name, ultimately helping him to gain a position as M.P. for Newcastle. Stoney, however, was actually a fortune seeker, who, coveting the Countess’s wealth and social advantage, had tricked her into marriage. Widowed by John Lyon, the Earl of Strathmore, the lady’s dowager status gave her the right to own property—something denied to married women. This included the sizable inheritance she had brought into the marriage, which attracted Stoney. Staging a duel against a libelous newspaper editor in defense of the countess’s honor, Stoney emerged wounded. Under the pretense of a dying wish, he asked the countess’s hand in marriage. She agreed, and once married, Stoney recovered miraculously.Unbeknownst to him, however, her fortune had been deeded into the care of trustees. Stoney soon began to abuse his new wife physically and mentally. In time, the countess sought a divorce. She won preliminarily in an ecclesiastical court, but Stoney conspired to kidnap her and keep her hidden. Stoney also employed mendacious newspaper stories and satirical prints in an attempt to sway public opinion against the countess. When she eventually escaped and continued proceedings, the utter reprehensibility of Stoney’s actions secured a divorce.

The cats in this print likely represent the countess’s actual pets, Angelica and Jacintha. Tellingly, Stoney had lamented in a courtship letter that he was not one of her cats, musing, “. . . were I Proteus, I would instantly transform myself, to be happy that I was stroked and caressed like them, by you.” Gillray twisted Stoney’s sentiment in order to depict Mary Ellen Bowes as a bad mother who preferred her cats to her children. In truth, both Stoney and her previous husband’s family had cruelly separated her children from her at length. In addition to the accusation of being a poor mother, the presence of the licentious footman, beckoning her to bed, suggests that she is an adulterous wife. Infidelity was one of the reasons argued for divorce in eighteenth-century England, though marriage was generally held to be inviolable. The best that most people wishing a divorce could expect from the ecclesiastical courts of the day was a legal separation allowing a couple to live independent lives without dissolving the marriage itself. Full annulments were rarely granted to men, and almost never to women. Occasionally, after the ecclesiastical courts refused to dissolve certain marriages, special dispensations from Parliament (in the form of acts) permitted individual-case divorces. Such legislation was usually aimed at safeguarding fortunes from “bad” women and illegitimate children.

The lives of Andrew Robinson Bowes, Esq. and the Countess of Strathmore, written from thirty-three years professional attendance, from letters, and other well authenticated documents. By Jesse Foot Published 1810 for Becket and Porter, and Sherwood, Neely, and Jones, by J. Bryan in London. Available from Open Library

As symbols, cats reiterate these social constructions of femininity that is motherly if it is good, and morally negligent—wanton, desiring, willful, chaotic, and vicious—if it is ill. Cats often connoted immoral femininity, following a tradition that emerged from the concatenation of felines, Satan, and witchcraft from at least by the early thirteenth century until the Enlightenment in the eighteenth century. Above the countess in the print, Gillray places a painting of Messalina, one of antiquity’s most scandalous women, so as to reinforce the negative characterization of the countess. .

Gillray’s anthropomorphized cats also stand for what they are—pets. By the eighteenth century, the former luxury of keeping pets was practiced at all levels of society. And by the middle of the following century, cats would easily eclipse dogs as favorite pets in London. In this regard, the countess’s cats reflect the real tendencies of keeping pets and the growing popularity of felines in Georgian England.

Yet, in Gillray’s Injured Count, S., both woman and cat represent ideas of illicit femininity. A woman’s proper role in the day, enforced by a male-governed society, was foremost as a wife and mother, and in the late eighteenth century, breastfeeding was a sign of a good mother. Gillray’s 1796 The Fashionable Mamma,—or—the Convenience of Modern Dress lampoons an aristocratic woman, who, dressed in a skimpy, high-fashion gown, dispassionately suckles her child while her coach, visible through a window, waits to shuttle her away. A painting above her head entitled “Maternal Love” offers a foil, depicting a peasant woman who lovingly nurses her child in a natural landscape. The distinction between the dispassionate aristocratic mother, authentic natural mother, and the countess unnaturally suckling her cats, speaks volumes.

Listen to Francesca Consagra discuss the exhibit and the roles of cats and dogs in history on a podcast episode of 15 Minute History.

Read more about pets, marriage, and satirical prints in early modern England:

Anna Clark, Scandal: The Sexual Politics of the British Constitution (2004)

Adrian Franklin, Animals and Modern Cultures: A Sociology of Human-Animal Relations in Modernity (1999)

Richard Godfrey, James Gillray: The Art of Caricature (2001)

Draper Hill, The Satirical Etchings of James Gillray (1976)

Linda Hults, The Witch as Muse: Art, Gender, and Power in Early Modern Europe (2005)

Cindy McCreedy, The Satirical Gaze: Prints of Women in Late Eighteenth-Century England (2004)

Wendy Moore, Wedlock (2009)

Oliver Ross McGregor, Divorce in England, A Centenary Study, (1957)

Walter Stephens, Demon Lovers: Witchcraft, Sex, and the Crisis of Belief (2002)

Douglas Cushing earned his BFA at the Rhode Island School of Design and his MA in art history at the University of Texas at Austin. His master’s thesis, written under the supervision of Linda Dalrymple Henderson, examines Marcel Duchamp’s relationship with the writings of the Comte de Lautréamont. Douglas is currently a PhD student in art history at the University of Texas at Austin and the Andrew W. Mellon Fellow in Prints and Drawings, and European Paintings at the Blanton Museum of Art.