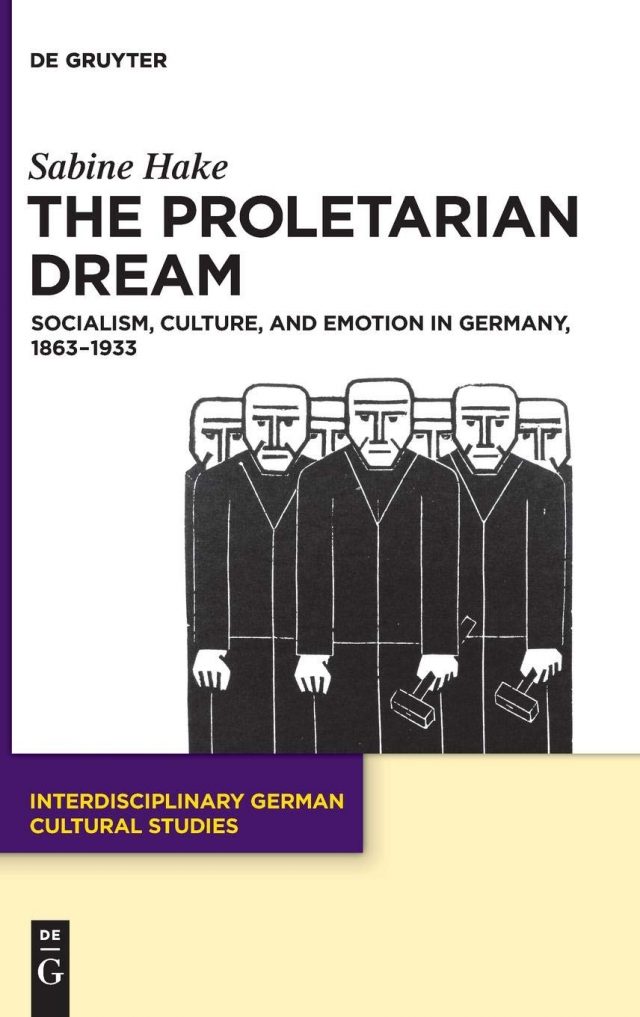

By Sabine Hake

The “proletariat,” imagined to be the most radical, organized, and active segment of the working class, never existed as more than a utopian concept, but it had a profound effect on German society from the founding of Social Democracy in 1863 to the end of the Weimar Republic in 1933. Over the course of seventy years, the idea of a proletariat, often simply equated with the working class, inspired countless treatises, essays, novels, songs, plays, dances, paintings, photographs, and films. All of these works shared the vision of a classless society, conveyed the importance of class unity and solidarity, and, in very concrete ways, contributed to the making of class consciousness. Some of the figures are familiar to scholars of German culture and politics, including Ferdinand Lassalle, Karl Kautsky, Franz Wilhelm Seiwert, Wilhelm Reich, John Heartfield, and Bertolt Brecht. However, the vast majority are unknown working-class poets, artists, musicians, and intellectuals. Today largely forgotten, dismissed, or ignored, these men (and they were mostly men) insisted on the workers’ right to be heard, seen, and recognized. At the time, their contributions gave rise to a rich and diverse culture of political emotions, attachments, commitments, and identifications. Today, these works offer privileged access to the social imaginaries that formed during a crucial period in the history of mass political mobilization. In particular, they reveal what it meant—and even more important, how it felt—to claim the name “proletarian” with pride, hope, and conviction.

Some of the figures are familiar to scholars of German culture and politics, including Ferdinand Lassalle, Karl Kautsky, Franz Wilhelm Seiwert, Wilhelm Reich, John Heartfield, and Bertolt Brecht. However, the vast majority are unknown working-class poets, artists, musicians, and intellectuals. Today largely forgotten, dismissed, or ignored, these men (and they were mostly men) insisted on the workers’ right to be heard, seen, and recognized. At the time, their contributions gave rise to a rich and diverse culture of political emotions, attachments, commitments, and identifications. Today, these works offer privileged access to the social imaginaries that formed during a crucial period in the history of mass political mobilization. In particular, they reveal what it meant—and even more important, how it felt—to claim the name “proletarian” with pride, hope, and conviction.

The workers’ demands for representation were part of larger political struggles associated with the worker’s movement and the working class, the Social Democratic Party of Germany (the SPD) and the German Communist Party (KPD). Given its formative emotional qualities, however, the proletarian imaginary cannot be dismissed as a mere function of party politics or political ideology. In ways not yet fully recognized, attachment to the figure of the proletarian became the basis of a vibrant alternative public sphere and a thriving socialist culture industry. Moreover, the countless stories and images of pride, hope, fear, rage, joy, and resentment made the worker a compelling figure in larger debates about modern class society and mass politics and contributed to the workers’ remarkable availability to socialist, nationalist, and populist appropriations. Marxist thought may have provided important concepts and theories but the enormous archive of emotions produced in the name of the proletariat forces us today to move beyond ideology critique—and to recognize the power of political emotions and of emotions in politics beyond traditional left-right distinctions.

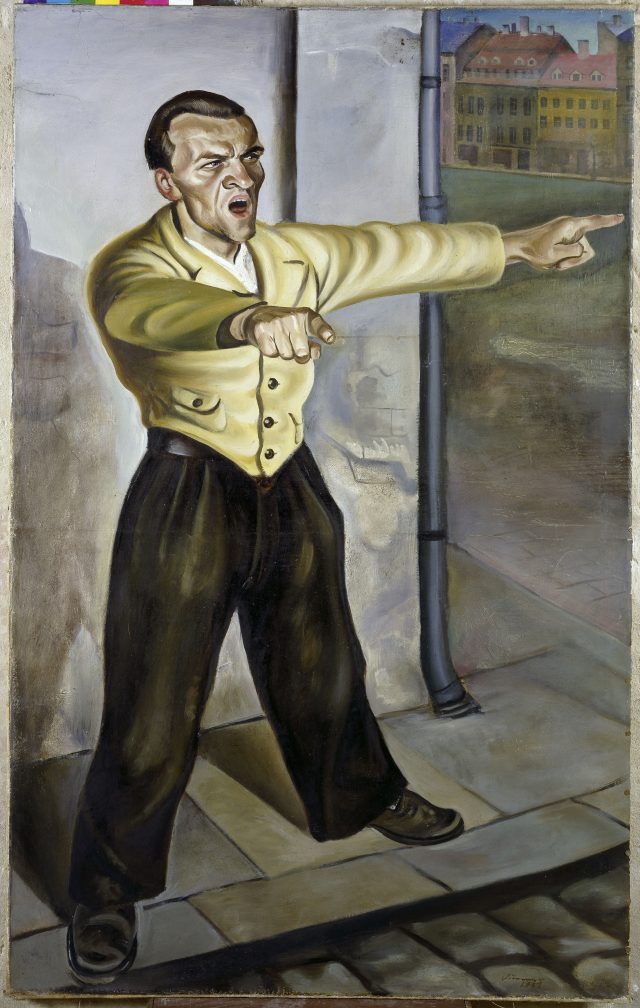

To give a sense of the scope of this “proletarian” cultural output, let’s take a few examples. The ubiquitous workers’ song books offered compelling models, from the Workers’ Marseillaise to the Communist International, for singing, feeling, and thinking in unison as workers. The Lutheran pastor Paul Göhre edited workers’ life writings with a view toward facilitating cross-class understanding that made workers’ emotions legible to bourgeois readers. Socialist party leaders, like August Bebel spoke about socialism as an emotional experience by describing his attachment to socialism in surprisingly sentimental terms, while Karl Kautsky railed against the dangers of emotional socialism. Kinderfreunde groups, started during the 1920s, organized summer tent cities where working-class children already practiced living in a classless society, in part to help them overcome feelings of inferiority. Communists modeled proper physical and, by extension, political stances, in the Rotes Sprachrohr troupe (Red Megaphone), which used a hard, rigid way of speaking, standing, and moving to equate class struggle with militant masculinity. And communist groups became involved in the sex reform movement and other radical initiatives through the work of Wilhelm Reich, who saw proletarian revolution and full genital health as mutually supportive goals.

Curt Querner, The Agitator (1930). An example of the habitus of militant masculinity favored by the German Communist Party (oil on canvas, Nationalgalerie Berlin. Copyright 2017 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst Bonn).

Aesthetic elements of these works were critical in the making of political emotions. For instance, a strong affinity between melodrama and the proletarian imaginary were represented by the aestheticization of suffering. Personified by the proletarian Prometheus, melodrama prepared the workers for the real hardships of class struggle. Socialist writers of working-class versions of the classic coming of age story, or bildungsroman, made character identification the most powerful vehicle for Bildung in the standard sense of education and in the Marxist sense of class formation. And in the work of the photo-montagist, John Heartfield, modernist techniques could give rise to distinctly proletarian structures of life and create an incubator for revolutionary action by making the violence inherent in montage.

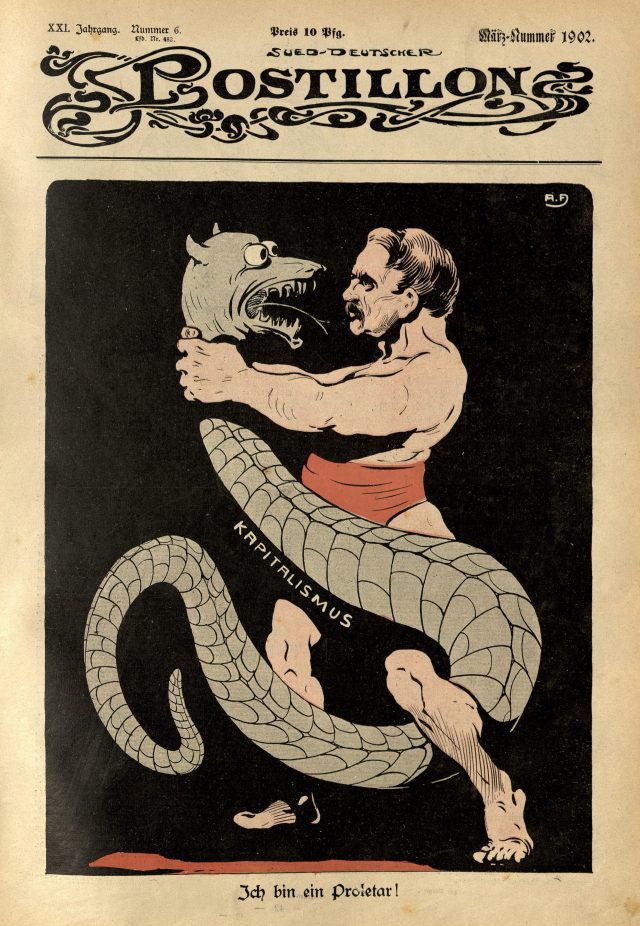

Cover of the journal Süddeutsche Postillon (21:6 1902), with the ideal-typical worker fighting the dragon of capitalism. (Ich bin ein Proletar!/ I Am a Proletarian!,” (With permission of Deutsches Historisches Museum, Berlin.)

While German Studies continues to neglect questions of class, a phenomenon worthy of further commentary (given the German contribution to Marxism and communism), The Proletarian Dream provides the first comprehensive overview of German working-class culture. Is is also is the first account of the culture of socialism that insists on freeing the culture of the workers’ movement from the fetters of ideology critique and recognizing its close connection to popular culture, mass culture, and the culture industry.

As a scholarly subject, the proletariat today may be considered outdated, irrelevant, and slightly peculiar. For me, its alleged obsolescence only confirms what Alexander Kluge once said about his reasons for writing about the proletariat—namely, that it is important not to “allow words to become obsolete before there is a change in the objects they denote.”

Sabine, Hake, The Proletarian Dream—Socialism, Culture, and Emotion in Germany, 1863-1933 (2017).

Several recent monographs in other disciplines address very similar questions in different contexts. The changing meanings of the proletarian in nationalist, regionalist, and anti-colonial movements are particularly obvious in Latin America and Southeast Asia and confirm the centrality of culture, including folk and popular culture, in generating political emotions and forging proletarian identifications:

John Lear’s 2017 book, Picturing the Proletariat, Artists and Labor in Revolutionary Mexico, 1908-1940 , highlights the ways radicalized workers in Mexico drew on indigenous traditions (e.g., Posada’s use of folk traditions in political printmaking) and internationalist iconographies (e.g., the proletarian Prometheus in the German socialist press) to support the struggles of workers in agriculture and industry.

Samuel Perry’s 2014 book, Recasting Red Culture in Proletarian Japan: Childhood, Korea, and the Historical Avant-garde, reconstructs the proletarian moment through the communist appropriation of Japanese woodblock techniques, the didactic goals of proletarian children’s literature, and the political avant-garde’s complicated relationship to their country’s imperialist practices.

Sunyoung Park’s 2015 book, The Proletarian Wave: Literature and Leftist Culture in Colonial Korea, 1910-1945 offers the corresponding Korean perspective, which includes close attention to the conditions of socialist revolution in rural societies and the unique contribution of socialist women writers.

Photo credit: Agitprop performance by the Red Megaphone Troupe (Grupa Rotes Sprachrohr).