By Mark Sheaves

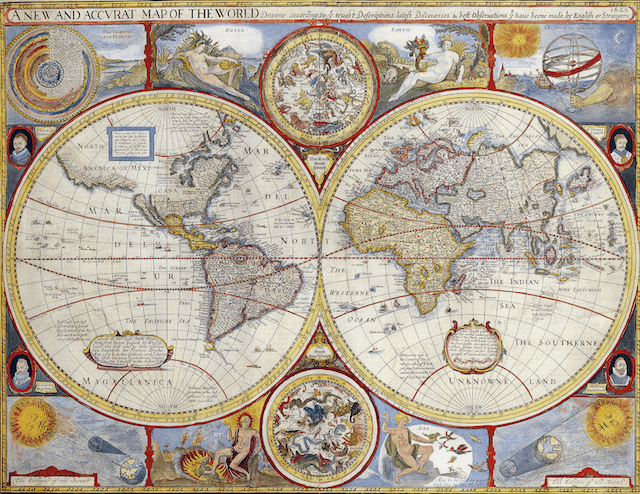

Between 1560 and 1660, English and Scottish merchants, ministers, travellers, and statesmen traversed the globe in search of adventure and economic opportunities. Frustrated by England’s weak economy, religious and political turmoil, and social conflict, these entrepreneurial individuals settled all over the world. But how did they integrate into those diverse societies?

In The Web of Empire, Alison Games argues that these private adventurers cultivated an ability to “go native” by adapting to local cultures. This cosmopolitan sensibility, Games contends, developed in the early sixteenth century as English merchants navigated the religiously divided and violent world of the Mediterranean. British people of all persuasions shared this ability to both read and mimic the customs they found in Madagascar, Japan, Tangier and elsewhere. Tracing their movements through published travel accounts, diplomatic reports, letters, and business papers, Games illustrates how they wove a web across the globe, facilitating the circulation of ideas, products, and people.

The English cosmopolitans examined by Games show how the mercantile activities of a coterie of adventurous individuals and the knowledge they disseminated formed the foundation for the first global English Empire based on trade. These individuals’ experiences explain how England developed as a major global power by 1660 despite the weakness of the English state throughout the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. The English Empire first emerged through a mixture of pragmatic interactions and forms of governance, and without state support.

Games also shows that this network of English people brought global knowledge back to the metropole, opening the horizons of the governing classes to the economic opportunities available in the world and fueling the imperial ambitions of the English monarchy. The rise of state interest in overseas expansion shifted English activity from a focus on private trade to an empire based on settlement from the 1650s onwards. Settlements in Ireland and then Virginia demonstrate that, with the rise of the state interests, an attitude of domination and coercion towards native people supplanted the cosmopolitanism of the earlier autonomous travelers.

Alison Games, The Web of Empire: English Cosmopolitans in an Age of Expansion, 1560-1660, (Oxford: OUP, 2008)

You may also like:

Mark Sheaves recommends Harry Kelsey’s Sir John Hawkins: Queen Elizabeth’s Slave Trader (2003)

Ernesto Mercado Montero discusses Ordinary Lives in the Early Caribbean: Religion, Colonial Competition, and the Politics of Profit, by Kristen Block (2012)

Mark Sheaves reviews Francisco de Miranda: A Transatlantic Life in the Age of Revolution 1750-1816, by Karen Racine (2002)

Bradley Dixon, Facing North From Inca Country: Entanglement, Hybridity, and Rewriting Atlantic History

Ben Breen recommends Explorations in Connected History: from the Tagus to the Ganges (Oxford University Press, 2004), by Sanjay Subrahmanyam

Christopher Heaney reviews Poetics of Piracy: Emulating Spain in English Literature (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013) by Barbara Fuchs

Jorge Esguerra-Cañizares discusses his book Puritan Conquistadors: Iberianizing the Atlantic, 1550-170 (Stanford University Press, 2006) on Not Even Past.

Renata Keller discusses Empires of the Atlantic World: Britain and Spain in the Americas, 1492-1830 (Yale University Press, 2007) by J.H. Elliott