In 1893 Aleko Konstantinov, one of Bulgaria’s most well known literary figures, traveled to the Chicago World’s Fair. Once in Chicago, Aleko—as he is remembered by Bulgarians—observed this now-famous spectacle along with the peculiarities of the “New World” itself. The Chicago fair was a formidable vision of prosperity and progress, by far the largest of all nineteenth-century fairs, with 27 million visitors and display space three times the 1889 fair in Paris. Aleko was mesmerized by the stately neo-classical pavilions that made up the fair’s so-called “White City” but was also drawn to the Midway Plaisance. The Midway was more about entertainment than trade and industry. It featured the world’s first ferris wheel, but also a whole world of exotic or “savage” sites, sounds, and flavors. In his recently translated travelogue entitled To Chicago and Back (Do Chikago i Nazad, first published 1894) Aleko details his complex impressions of the world, including his home country Bulgaria, on display. But it was the New World itself, on and off the fairgrounds, that most dazzled and disturbed Aleko.

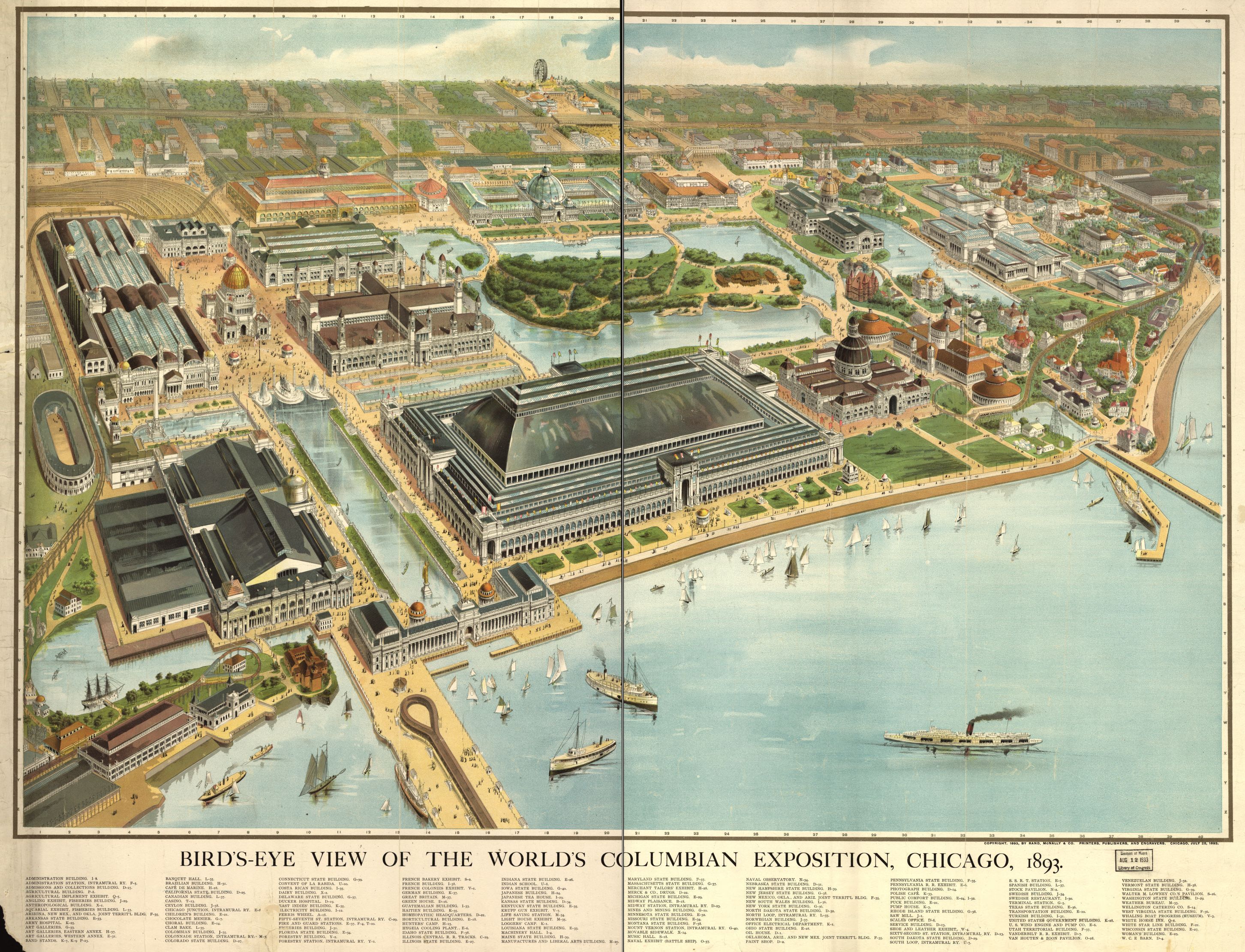

Bird’s eye view of the World’s Columbian Exposition, Chicago, 1893 (via Library of Congress)

Historians have spilled plenty of ink on the world’s fair phenomenon—namely how nations and empires projected and encoded power at these elaborate exhibitions. But the reading of fairs, especially by “non-Western” visitors has been much harder to unearth, with few such records left behind. Aleko’s reading of the fair’s sights, sounds, and smells then is a rare artifact. He was, after all, a Bulgarian from the outermost edge of Europe, a region that had been under direct Ottoman rule for five centuries and had only become autonomous in 1878. By all accounts, the fair’s extravagant displays of American wealth and might stunned Aleko, who was also impressed by the range of other, as well as Japanese, exhibits. Bulgaria’s tiny pavilion, in contrast, was a clear embarrassment. As Aleko noted with his characteristic irony, the Bulgarian pavilion tucked away in a “dark alley” next to the Ottoman pavilion was pathetic by all measures, except possibly in comparison with the Greek pavilion with its mere “sack of olives.” As Aleko snidely quipped of Bulgaria’s southern neighbor, “Why couldn’t they keep quiet, and mind their own poverty?” Aleko was even more annoyed by Bulgaria’s paltry kiosk labeled “Bulgarian Curiosities” on the Midway. As he ruminated with deadpan irony (and Eurocentric denigration), Americans will surely mistake Bulgarians for a “South American tribe” given the handicrafts on display, in spite of the Turkish-Moorish style of the kiosk.

Aleko Konstantinov (via Wikimedia)

Aleko’s concerns about appearing poor, “Oriental” or “savage” was also tempered by a growing sense of unease in the face of American “progress.” His long trip was punctuated by bouts of disillusionment as he wearied of the pace of American life, “the mad motion, of the railways, ships, and trams…and those worried faces…those silent lips, already unable to smile. So cold!…But when will we live?” But the climax of his disenchantment comes when he visits the Chicago slaughterhouses—a popular tourist destination for fairgoers at the time. The stench of pig death is so putrid and overpowering that Aleko almost throws up several times and nearly loses consciousness on his slaughterhouse tour. He chokes on the “murderous stench” until he finally yells “I’m dying!” His revulsion is physical as well as moral and he ruminates, “What has brought us to this place?” Turn of the century Chicago was the epicenter of modern meat production, with its massive stockyards, slaughterhouses, and meatpacking industry. But Chicago’s most important offsite display of “progress” then did not always have the desired effect; that is to impress the world with American might. On the contrary, it was the sight and smell of industrialized meat production and the mass slaughter of animals that sent Aleko reeling, questioning modern progress.

Chicago World’s Fair 1893 (via DPLA)

He was not the only one, of course, to look askance on the costs of progress and on the ills of the slaughterhouse in particular. A global vegetarian movement was on the rise in this period, in part fueled by ethical considerations raised by modern slaughterhouses such as those on display in Chicago. Interestingly the first Vegetarian Federal Union had an exhibit at the Chicago fair, and the 3rd International Vegetarian Congress was held in Chicago that year. Aleko was not a vegetarian and his visit to the Chicago slaughterhouse did not make him into one. He indulged with pleasure in a kebab at the restaurant in the “Turkish Village” on the Midway, served up by Americans in fezzes. But the experience did create a long shadow over his impressions of the glories of the fair and the New World. His readers can continue to walk in his steps, and imagine this lone Bulgarian’s journey to the future.

![]()

You might also like:

Whisper Tapes: Kate Millett in Iran by Negar Mottahedeh (2019)

Purchasing Whiteness: Race and Status in Colonial Latin America

US Survey Course: American Capitalism at home and abroad

![]()