My favorite director made a movie about my PhD dissertation topic 70 years before I wrote about it. The problem was that I didn’t find out about it until I was several years into my alt-ac career. Discovering the movie was the catalyst I needed to write a book I never thought I’d write.

OK, the movie isn’t exactly about my dissertation topic, American-backed land reform in occupied Japan, but it has some striking overlaps. The first film Akira Kurosawa made under the American censorship regime that existed during the postwar occupation of Japan was No Regrets for Our Youth (Waga seishun ni kuinashi). In the film, legendary actress Setsuko Hara changes from liberal bourgeoisie to radical rural activist. How her character plans to elevate farmers’ standards of living is left vague – the Americans would not unveil the transformative land redistribution program that I wrote about for another year – but the language she uses when envisioning a bright postwar future is that of General Douglas MacArthur and his staff of reformers. Their goal, and that of Hara’s character, was to “liberate” Japanese society by replacing “feudal” mores with “democratic” ones, and to do it before local communist reformers could try their own brand of remodeling. At a time when over half of the Japanese workforce was in agriculture, transferring the ownership of farmland from landlords to tenants was an essential part of the program, and one that the American occupation authorities pursued with real enthusiasm.

I’d known about Kurosawa for most of my life. As a teenage cinephile I fell in love with his 4-hour epic Seven Samurai (Shichinin no samurai), which I first saw on a two-tape VHS release from Blockbuster. The passion for movies I developed back then intensified during graduate school, when I found myself in dire need of a hobby, an escape, and a creative outlet. History had always been my main hobby, but now that it was for all intents and purposes my job, it was more burden than pleasure. Movies, unrelated to my dissertation topic, provided the distraction. I watched an average of two a day, mostly arthouse classics. I started writing about what I was watching and eventually found an outlet that paid me a bit and sent me to several of Austin’s film festivals with a press pass.

It was easy to justify spending more time on movies than on my dissertation, and I did, but somehow I finished the latter and then put academia mostly behind me. I stayed on campus, but in a staff role, and with my access to the libraries I sourced hard-to-find, impossible-to-stream movies through interlibrary loan. With a bias toward Japanese film, an affinity stemming from the three years I spent living in northeastern Japan, I’d now seen most of the major works of Kurosawa, Yasujirо̄ Ozu, and Masaki Kobayashi – three directors long held in high regard among international movie buffs. I also got married, to a woman I met in line for a movie at South by Southwest. Kathryn has a history degree as well, and our first conversation involved WWII submarine movies.

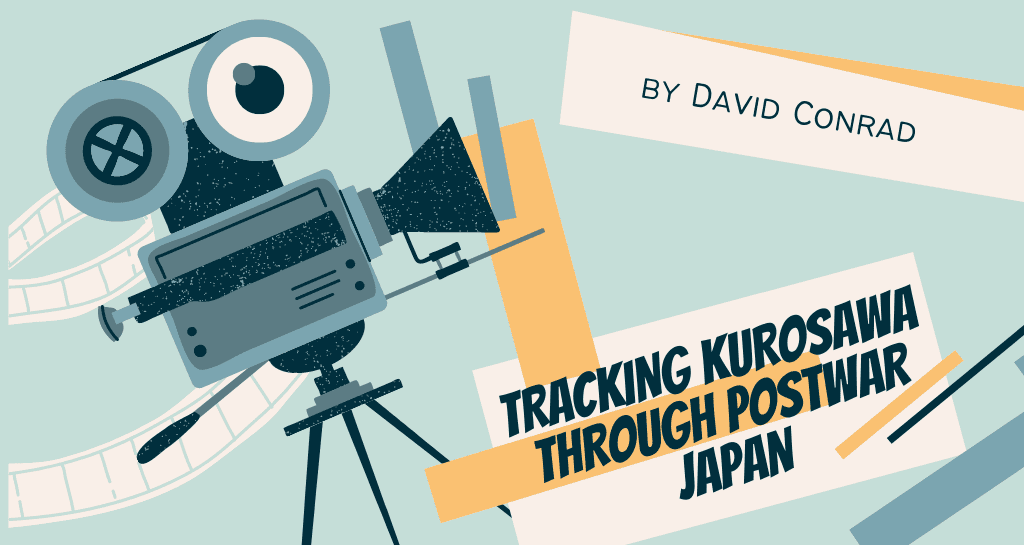

1946’s No Regrets for Our Youth was one of the last Kurosawa titles I encountered, but it put me right back in that dissertation headspace – in a good way. It was a perfect crossover of the topic I’d spent years writing about and the medium I’d dived into to avoid doing that very writing. Thinking that you could surely find similar overlaps between Kurosawa’s other movies and the historical moments in which they took shape, I asked Kathryn if I should do a YouTube series on the topic. With her background in film production, she gave me good advice: “You should write a book instead.” If we’d known about the looming onset of the COVID-19 pandemic or the much more joyous arrival of our two children that would occur during the writing, it might have seemed like an even more daring suggestion! But I took her advice and the result is my new book, Akira Kurosawa and Modern Japan.

Kurosawa’s solo directorial career spanned exactly 50 years, from 1943 to 1993. These were, by historical coincidence, five of the most turbulent and transformative decades in Japan’s history, and Kurosawa’s work reflects the dynamism of the era in both intentional and unintentional ways.

The first part of the book examines the movies a young Kurosawa made during the war while under the power of an ultranationalist censorship regime. Part Two traces his maturation during the seven-year American occupation, whose censorship Kurosawa later described as comparatively light but that he sometimes railed against in the moment. Part Three finds subtle connections between Japan’s era of high-speed growth – its “economic miracle” – and Kurosawa’s big-budget epics that won international film awards and put the director on the world map. These were the movies that directors like Sergio Leone, George Lucas, and Steven Spielberg would remake, adapt, and homage for years to come. Part Four follows Japan’s expanding role in the international community in the form of tourism campaigns, cultural exports and “soft power,” and engagement with issues of global concern like the environment and nuclear power. In all eras, changing ideas about issues such as sex and sexuality, social welfare, and world affairs gave shape to Japan’s experiences and to the stories Kurosawa told.

My key primary sources were the movies themselves. Each of Kurosawa’s 30 official films receives its own chapter. The most famous of them have been written about many times, but never quite like this. The 1985 samurai epic Ran, an adaptation of King Lear, is usually analyzed in terms of its themes of loyalty and revenge, and critics emphasize its striking production design. In this book it is a springboard to discuss disability rights, 1980s feminism, contemporary urban theater, the visibility of queer people, and elder care. Kurosawa’s 1958 medieval action-comedy The Hidden Fortress (Kakushi toride no san akunin), famous as an inspiration for Star Wars, provided me an opportunity to write about the birth of neighborhood preservation committees, Japan’s national parks and protected national treasures, the significance of the gold standard, and the expansion of rail and rail advertising in the economic boom years.

In some cases I have departed from longstanding convention by offering my own translations and transliterations of titles, as in the case of Kurosawa’s 1955 film, made in response to a US hydrogen bomb test that claimed one Japanese life and triggered a food safety panic. Beyond Kurosawa’s filmography, I make reference to several dozen other relevant movies, some famous and some quite obscure. A full list of them is available at https://letterboxd.com/davidconrad/list/movies-mentioned-in-akira-kurosawa-and-modern/.

Books and articles from scholars working in the fields of history, economics, religion, public policy, medicine, design, literature, entertainment, food, and other topics helped me fill out the study. I already had a good grasp of the scholarship on the earlier periods covered in the book, but I knew little about more recent decades apart from what I’d learned and observed during my time in Japan. Firsthand experienced helped me know what questions to ask of the literature.

On many occasions I was thrilled to find even stronger overlaps than I expected between on-screen content and off-screen context. For example, Dersu Uzala, the film Kurosawa made in 1975, is the true story of a turn-of-the-century explorer who mapped the Russian Far East for the Tsar. Kurosawa spent a year shooting in Siberia during the mid-70s Cold War thaw that eased tensions between the USSR and the Western bloc, of which Japan was an important if ambivalent part. In the movie, an indigenous woodsman helps keep the St. Petersburg man alive in the harsh elements of the taiga. The same year that movie came out, a Japanese documentary called The Man Who Skied Down Everest hit theaters around the world and even won an Oscar. By coincidence, it also tells a story of adventure in the Asian hinterland and the relationship between indigenous peoples and the sojourners from the so-called first world who rely on them. The first Japanese team to summit Mt. Everest documented their 1970 climb and the nearly-fatal titular stunt of one of their members, but they also captured the ice collapse that killed 6 of their Sherpa porters. Prior to the accident, the team had screened Seven Samurai for the Sherpas on a small TV at 15,000 feet. Such seemingly-accidental resonances between Kurosawa’s stories and current events dot the pages of the book.

Yet Kurosawa’s interests and temperament sometimes put him at odds with his colleagues and countrymen. Nowhere is this more clearly on display than in Part Three of the book, which discusses Japan’s famed postwar economic miracle. As incomes more than doubled and high-end consumer goods like TVs, refrigerators, and cars became commonplace, filmmakers like Ozu (see 1959’s Ohayо̄) and Ichikawa Kon (see 1962’s Watashi wa nisai) had their characters desire and acquire the comforts and conveniences of midcentury life. In Kurosawa movies from this era, on the other hand, such creature comforts tend to creep in at the edges of the story, or in the case of his period pieces are wholly absent. Kurosawa was prone to jeremiads and was something of a cinematic Cassandra, but as his movies grew more ambitious and more costly, the reality of Japan’s postwar transformation is evident even in their often-bleak visions of past and present.

Akira Kurosawa and Modern Japan is a work of history rather than film criticism, and that informed the choice of images. There are 60 images in the book, none of them movie stills. The oldest is an 18th-century illustration that pertains to Kurosawa’s final film, and there are also rare images from the Meiji and Taishо̄ periods that predate Kurosawa’s career. The most recent image is from an event in 2019, over 20 years after Kurosawa’s death. Towards the middle of the book is a striking snapshot of a 1970s protest that I licensed from the photographer. I’m excited for a wider audience to see it, and many other images, for the first time.

The book is written for a general audience, especially people who love Japanese media and want to know more about the historical reality that underpins it. Writing it thrust me back into the academic process in a way that I wasn’t looking for but thoroughly enjoyed. I hadn’t envisioned writing this book, but now I am looking forward to the second and third books, whatever they may be.

David A. Conrad received his Ph.D. from UT Austin in 2016 and now works in the Office of Graduate Studies where he tries to make grad students’ lives easier. During his spare time he reads and writes history, binge-watches Criterion Channel movies, and raises two small children.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.