From the editors: This article first appeared in QT Voices, which is the online magazine of the LGBTQ Studies Program at The University of Texas at Austin. For the original article see here.

Student government is an essential part of student activism. It’s one of the most direct lines that students have to university administration. In fact, the University of Texas student government says right in their mission statement that it “was established in 1902 to serve as the official voice of the student body at The University of Texas at Austin.”

Yet, in 1902, the student body looked drastically different than it does today. UT’s past includes the “Gay Purges” of the 1940s, and excluding Black students and faculty until 1956. As Dr. Ted Gordon’s Racial Geography Tour makes clear, the architecture of the University of Texas itself is a testament to these and other exclusions. This past makes the election of Toni Luckett in 1990, UT’s first Black, Lesbian, student-body president, not only historic, but groundbreaking.

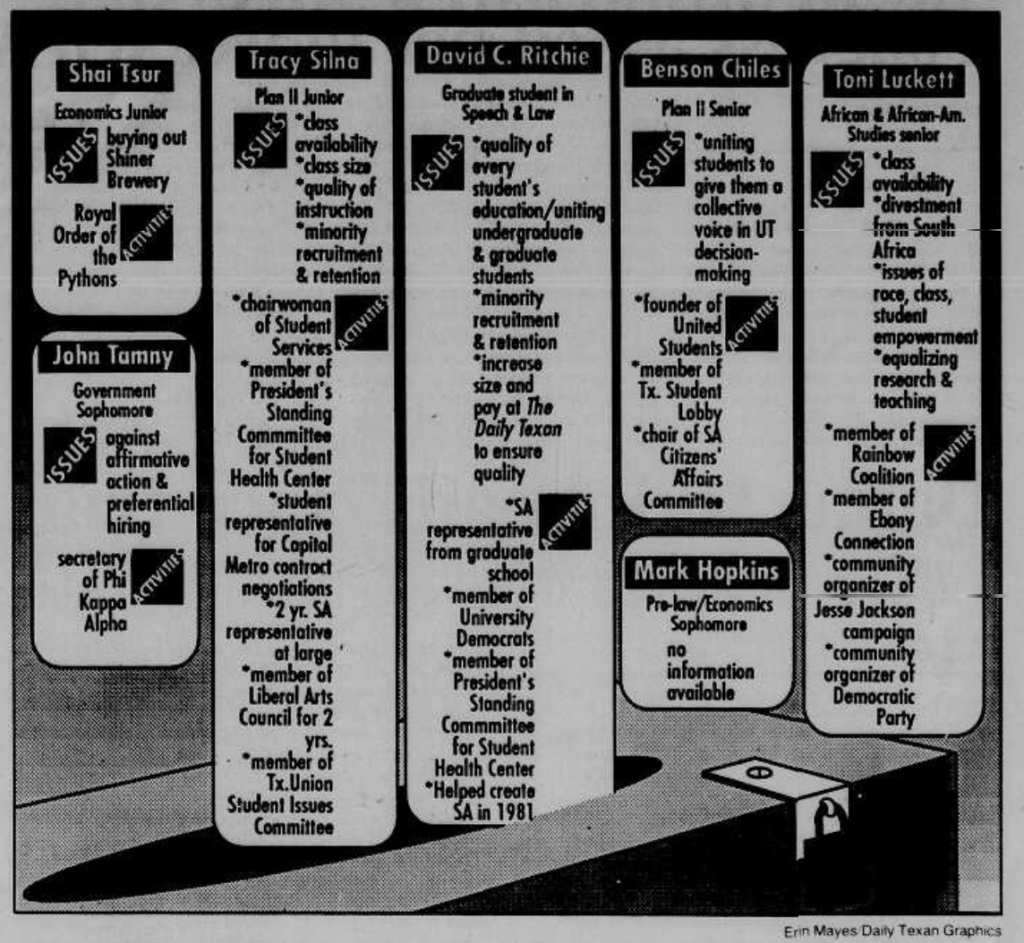

The first time Luckett’s name appears in the Daily Texan is January 23, 1990. A photo pictures Luckett, front and center, fist raised, marching alongside other pro-choice activists at a rally that marked the anniversary of Roe v Wade. The caption identifies her as “Toni Luckett, an Afro-American studies major.” She is not “soon-to-be-President Luckett”, not “leader.” Yet among the eight people running for president, Luckett’s platform looked different from the beginning. Among her primary concerns were “class availability,” “divestment from South Africa,” “issues of race, class, student empowerment,” and “equalizing research & teaching.” None of these were tremendously radical, and according to the Texan, her points aligned quite well with the general concerns of the student body. What set her apart were her qualifications, her methods, and of course, her identities. While many students had experience in student government and majors in government, law, or economics, Luckett had a different set of skills. She is the only African and African-American Studies major represented, and her activities included the Rainbow Coalition and Ebony Connection. She was also listed as a community organizer for Jesse Jackson and the Democratic Party. Her platform focused on gathering student support and pressuring the administration. She wanted to work outside the confines of the established avenues for student input. When she is jointly endorsed by the Daily Texan (along with David Ritchie), the writer has to stipulate that Luckett did not seek their endorsement as “she wanted a populist campaign, not influenced by existing institutions.” The article says “conventions don’t bind Luckett” and “Luckett has the fire to take the SA a step beyond the institution it is and make it into a true student coalition.”

In many ways, the article was absolutely correct. After a runoff between Luckett and Plan II major, Tracy Silna, Luckett won the election. She took 56% of the vote, with an election turnout that was far better than the general race. When compared with Silna, the Texan asked: “Does the Student Association need modifying and improvement from one who has worked within its channels or radical reform from one who has worked outside them?”

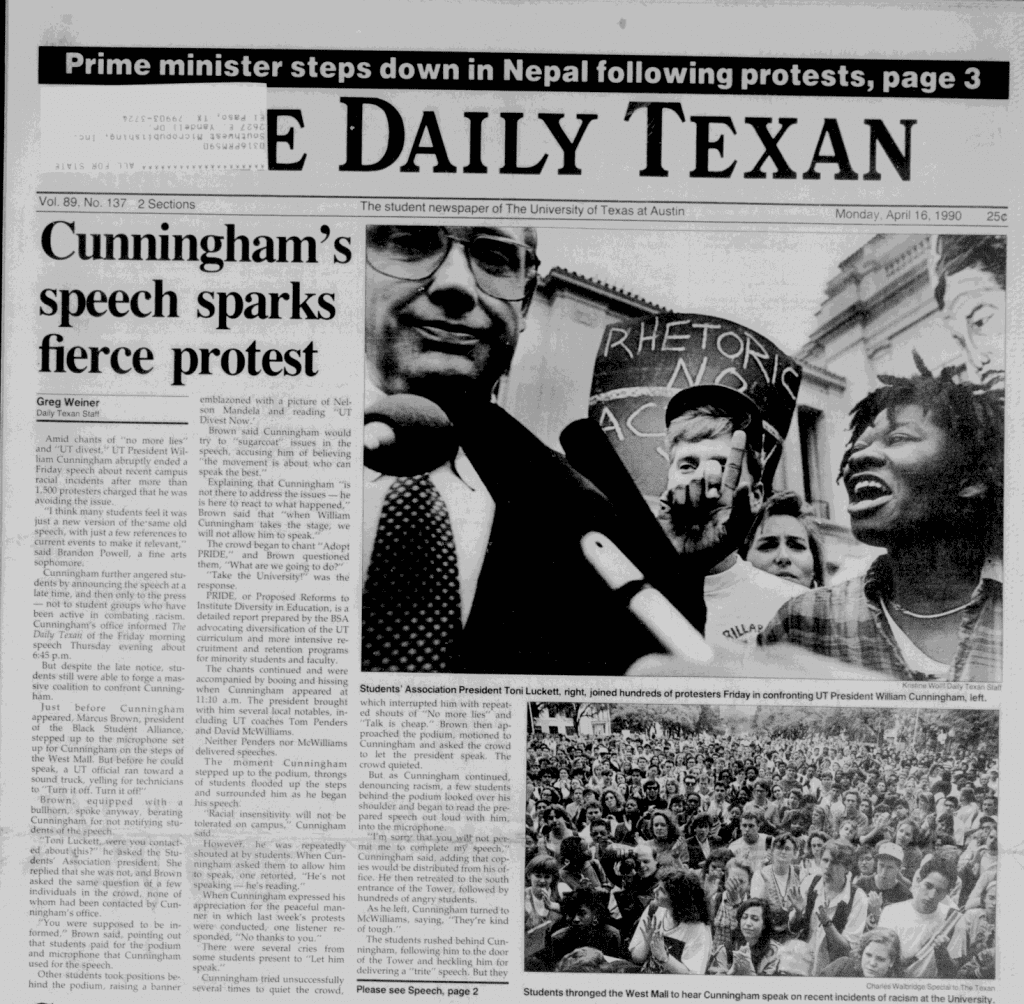

The students chose. Over the next year Luckett’s name frequented the Daily Texan. She remained at the forefront of representing students. Whether it was boycotting with law students to protest the lack of diversity in the profession, marching with students in response to incidents of racial injustice, or going through the day-to-day meetings, appointments, and planning required of the president, Luckett was there. Perhaps most notably, Luckett, along with the Black Student Alliance president, Marcus Brown, flooded the steps with hundreds of other students during what was set to be one of UT President Cunningham’s “trite” speeches. Eventually frustrated by the interruptions, Cunningham left to return to the tower, where students followed only to be met with locked doors and UTPD. Despite this they gave speeches outside the tower and rallied together. Luckett said, “he’s locked the doors on us to our tower.”

Our tower. This line brought me to a similar expression in another one of Luckett’s other speeches. At a march, Luckett pointed at the tower, drawing hisses from her fellow students. In response, Luckett asserts, “we don’t have to boo it—we just have to take it.”

I don’t want to suggest that Luckett’s presidency was a seamless time of transformation. In looking through the archives, I found article upon article discrediting the experiences of minority students, claiming Luckett and Brown are “crying for handouts,” calling them a “merry band of idiots.” One article claimed exhaustion at the idea of discussing racism: the writer is “so sick and tired of hearing about this racial issue that I could puke.” These sentiments, these blatant expressions of hate, prejudice, and ignorance, are only a portion of that which was published. Incidents of racial prejudice and homophobia persisted throughout Luckett’s time as Student Association president, especially in fraternities through West Campus annual parties such as Roundup. Yet as we fight for a more inclusive university even today, we have to applaud and recognize Luckett for paving the way for future students. She saw the then 88-year old institution of student government, one that had only served students who looked like her for less than half of that time, and chose not to boo it, but to take it.

Banner image courtesy of Enrique Jiménez

Brynna Boyd (she/her) is a third-year undergraduate student pursuing majors in Communication & Leadership, African & African Diaspora Studies, as well as Plan II Honors with a Minor in Educational Psychology. She is president of the Black Honors Student Association, a peer mentor, and a member of Texas Novas spirit group. Her research interests include the experiences of historically underrepresented students in relation to cultural taxation, overall wellbeing, and academic success. As a Mellon Mays fellow, she plans to explore these issues and how they are influenced or perhaps amplified by national movements, through analyzing the communication structures of student organizations and university entities. She intends to continue devoting her time and research toward educational equity.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.