The French entrepreneur Francois LaBorde was born April 16, 1867 in Arudy, France. He arrived at Rio Grande City, Texas by steamboat up the Rio Grande in 1878. Soon after settling there, he met Eva Marks, the daughter of a French immigrant father and a mother who was born in Mexico but raised in Texas. The French connection must have been part of their initial attraction. They married on March 2, 1896 and their first daughter, Blanche, was born a year later. Francois fostered his love for French architecture in the LaBorde House, the opulent hotel he built and filled with exquisite European fixtures. His hotel still operates, and is one of the most elegant hotels in south Texas.

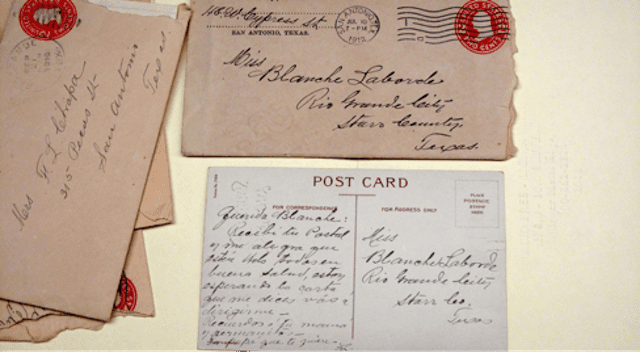

In the course of my research on the LaBorde House, I came across a hidden gem. Deep within the Chapa Family papers housed at The University of Texas at San Antonio, one box filled with an assortment of archival items, including legal documents, personal correspondence and photographs offer a glimpse into the LaBorde family. Among these items are four handwritten letters, exchanged between François LaBorde and his daughter Blanche. These letters reveal intimate details about their lavish lives and the unconditional love they had for each other.

Francois LaBorde died at the age of 50, of a possible suicide. Blanche was only twenty years old when tragedy struck their family, but she was fortunate to know how much her father loved her. These letters are a portal into their close father-daughter relationship as well as many social customs of the period. They reveal a warm-hearted man who is only remembered in history as the visionary of a grandiose hotel. Here’s a quick peek at the LaBordes’ exceptional life.

From: 118 W. Cypress St.

To: Miss Blanche LaBorde

Rio Grande City, Starr County Texas

July 10, 1912

My Dearest Blanche,

I received your postcard and I am glad that you all are doing well and in good health. I am still waiting for that letter you said you will send me. Greetings to your mom and little sister.

Dad who loves you, F.L.*

Fifteen-year-old Blanche, the oldest daughter of Francois LaBorde received this post card from her father with a scribble on the front image that reads “Be Happy.” The letters were written in perfect Spanish by her dashing father, a French merchant who had immigrated to Rio Grande City, Starr County Texas, around thirty years earlier. The LaBordes were an atypical family in South Texas thanks to their wealth and social status, but were, like many other families, representative of the region’s common intermarriage and multiculturalism.

LaBorde had a keen eye for business and he quickly integrated himself to the community. Around 1890, he opened a general merchandise store in Rio Grande City and also maintained a strong economic connection to his homeland. He knew the popularity of leather gloves in the European market and made a successful business of shipping primary materials (tanned goods) to French glove makers. His family also had a strong connection with San Antonio. In fact, his wife and their five children spent most of their time at 118 W. Cypress St., their San Antonio home, while LaBorde lived in a palatial Parisian style home he built for the family in 1899 in Starr County. LaBorde’s businesses kept him busy in Rio Grande City, but the family traveled back and forth between the two homes.

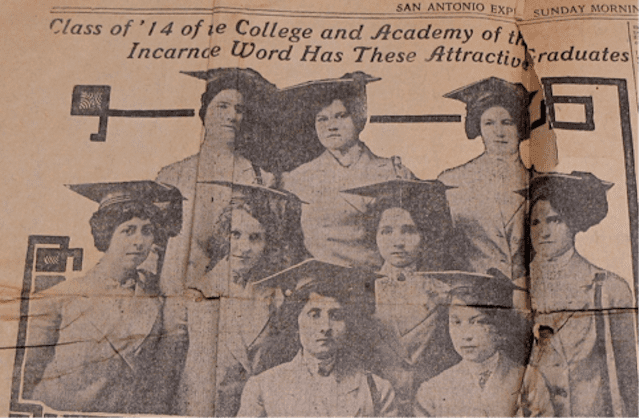

Blanche attended the College and Academy of the Incarnate Word in San Antonio run by the Sisters of Charity. “No pains are spared by the Sisters to mold the character of the young ladies,” explained the college’s handbook. Blanche and her classmates were instilled with “the great guiding principles of honor, rectitude, and piety.” In 1914, Blanche graduated, and from what the letters reveal, she moved to the family home in Rio Grande City soon after.

In December 1914, eighteen-year old Blanche was staying in their Rio Grande City home, while her father was in San Antonio. The letters exchanged between the two, reveal health problems as the likely reason why he was staying with his wife and other children away from Rio Grande City. His anguish over his business matters comes through as he makes requests to Blanche to deal with some urgent business. As usual, Francois wrote his letters entirely in Spanish.

From: F. LaBorde 118 W. Cypress St. San Antonio TX

To: Miss Blanche LaBorde, Rio Grande Starr County, TX

San Antonio, Dec. 10, 1914

My Dearest Daughter,

We have received all of your nice letters, and just now the last one, where you complain that I have not replied? But I am doing it now, letting you know that I am glad that you are doing well, but it upsets me to read that you are losing weight so fast, you tell me you weigh less and that is not right. Take care of yourself, so that upon your return, you are just as healthy as when you left.

I hope you have a nice, fun time there, and that when it is no longer convenient for you to be there, you come up. Tonight I will write you a long letter. You know that I have your Christmas present ready, and as soon as you arrive I will give it to you.

Would you do me a favor and tell Tina that I am doing well, that I no longer have health issues. Your father, who loves you, wishes you stay healthy.

LaBorde

P.S. I am sleeping really comfortable during my nap (siesta) there is no more telephone noise to bother me. L.

Another letter however, also includes her mother’s script, which reveals that as a Texan, she was much more comfortable communicating in a mix of both English and Spanish.

From: F. LaBorde 118 W. Cypress St. San Antonio TX

To; Miss Blanche LaBorde, Rio Grande Starr County, TX

San Antonio, Dec 16, 1914

Miss Blanche LaBorde,

Rio Grande Texas

[Scribbled in Spanglish on top margin]:

The baby went by to see the portraits of Chiffonier and said aunty is sure pretty here, her feelings are hurt because Caterina told her last night that her aunty had said that she didn’t love her. She did not come outside all day, poor baby. Last night we went to see the window displays. It is really cold, but we are all wrapped up, greetings to everyone. Mamma

My dearest daughter,

I received your sweet letter of last Friday and we were so glad to read that you are doing well healthwise and that you had fun at the last Saturday’s dance. Let me know how soon you will come back, since you can come back as soon as you wish.

Please find out how much I have to pay for the county taxes and when I have to pay them. Also, ask Mr. Monroe when Don Jose M. Longoria will pay me what he owes me.

Without further ado, lots of greetings to all of you, and “good luck,”

Your father who loves you,

LaBorde

[Scribbled postscript by Eva in Spanish:]:

And I did not write because I do not have enough room, but it is already 9, and I am just having breakfast, the boys are off to school, your dad is getting up and I think the express is coming. Kisses to everyone.

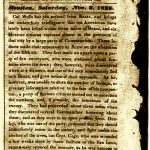

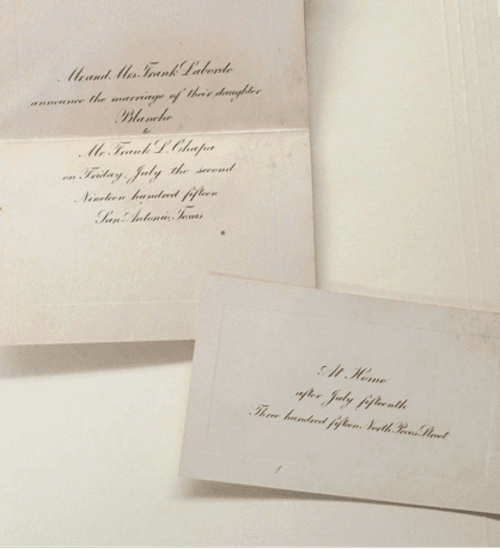

Things changed for the LaBorde family after Blanche’s graduation. Although there is a one-year gap in correspondence, it can be assumed that sometime in that year (or perhaps earlier) Blanche met her dashing soul mate. On Friday, July 2, 1915, nineteen-year-old Blanche eloped with Frank Chapa, a descendant of the Canary Islanders who settled San Antonio, where he was born and raised. They informed her parents via telegram and the news baffled them. The telegram written in broken English reads,

Blanche LaBorde

In care of Frank Chapa,

Your telegram received very sorry the way you do it. Mother and Father suffering from the shock but god help you be happy. Your loving mother and father.

LaBorde

It is likely that Eva wrote the telegram, since Francois typically communicated in Spanish. Or perhaps out of anger and shock, he managed to piece together this succinct message in English. The frustration over this rash decision could not have lasted long, since the LaBorde’s officially announced their daughter’s marriage soon after.

Second Card reads: At home after July Fifteenth Three hundred fifteen North Pecos Street.

It is important to note that in this official wedding announcement, Francois refers to himself as Frank. He was a man who adapted his name to every occasion. In the 1910 census of Starr County, he is listed as Francisco, his business cards had the name Francois, his daughter’s wedding announcement, Frank, and people in the community of Rio Grande City knew him as “Don Pancho” (the typical Spanish nickname for Francisco). His social and business ties forced him to interact with the Spanish, English, and French speaking worlds so often, that he was comfortable transforming his personality as he saw fit. He wrote his letters to Blanche in Spanish but all of his children spoke French. In fact, Rio Grande City neighbors remembered hearing the family speak French often. In a 1982 interview, LaBorde’s youngest daughter Ernestine (only 7 years old when her father died), said she remembered her father as “a warm vital man of good spirits with a stylish mustache, a bon vivant who enjoyed luxury and travel. I always addressed him in French, the minute he walked in the house, I would say: ‘Je vous aime beaucoup’ and he loved it.” LaBorde was most comfortable communicating in either French or Spanish, his son-in-law, Frank Chapa, recalled that he spoke little English.

A letter written a year after their elopement reveals that whatever pain was caused by Blanche and Frank’s sudden marriage became a thing of the past for the family.

My Dearest Daughter Blanche,

I have received your lovely letters, one with the date of the 17th and the other last Sunday and I thank you for your affection, and I am glad that you are all in good health.

The business matters that brought me down here seem to be ok, but I will soon find out.

I am working on drafting plans and budgets for the hotel. Constantino was here studying them, but we have to see the architect for certifications. There is great possibility that it will be approved.

Take good care of your mother, give my best regards to her and your little siblings and Frank and all of the Chapa family in general.

Your dad who loves you, F. LaBorde

The hotel that Francois is referring to in this letter is actually the additions made to his family’s home to create the LaBorde House. He transformed the palatial home of the LaBorde family into an exquisite hotel that still stands today. The celebration of his accomplishment was unfortunately short lived. A few months after the official opening of the hotel, on the morning of August 11, 1917, Francois was found dead. The official death certificate reveals the cause of death was a gunshot wound in the head. It is still a mystery to this day, weather it was an accident, a business feud gone horribly wrong, or a suicide.

What is a fact is that these letters reveal the immense love LaBorde had for his daughter. One can only imagine the void left in Blanche’s life when her father died and the incredible loss and heartache over the sudden end to their correspondence.

Just as Francois was a visionary in his business endeavors, Blanche also proved to have had a keen eye for choosing a husband. They were married for 45 years and had two girls, Marie Ernestine and Beatrice. In 1960, Blanche died of pneumonia but Frank lived to be 90 years old, until his death in 1985. The name Blanche lived on in the LaBorde family. Blanche’s younger brother Leonard, named his daughter after her in 1927. The memory of Francois LaBorde also lives on in Rio Grande City. His majestic French-style hotel still draws visitors to the area thanks to his exquisite taste and French heritage, which reminds tourists and locals alike of the conglomeration of cultures that met along the Rio Grande.

*The letters were written in Spanish and are Lizeth Elizondo’s translation. All of the letters and images are from: Francisco A. Chapa Family Papers, MS 405, University of Texas at San Antonio Libraries Special Collections.

You may also like in Texas History:

Confederados: The Texans of Brazil

“The Battle of Bandera Pass and the Making of Lone Star Legend”

A Texas Ranger and the Letter of the Law

“The Die is Cast”: Early Texans Face the Comanches

Standard Oil writes a “history” of the old south

Stephen F. Austin visits a New Orleans bookstore

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.