The Descendants, directed by Alexander Payne, opens with a voice-over by protagonist Matt King (played by George Clooney), a wealthy Oahu lawyer, about how everyone assumes that Hawaii is a paradise. We quickly learn, however, that there is trouble in paradise. Matt’s wife, Elizabeth, is in a coma from a boat-racing accident, and Matt, who describes himself as the “back-up parent,” has become the sole care-giver for his two troubled daughters, Scottie and Alex. Elizabeth’s accident comes just as Matt is preparing to sell 25,000 acres of land on Kauai contained in a family trust, for which he is the sole trustee. The trust is due to expire in seven years and the many cousins in the King family have agreed to sell the land to a real estate developer.

The land is a legacy from Matt’s great-grandmother, a Hawaiian princess and direct descendent of Kamehameha, who married Edward King, the descendant of American missionaries. Although the family is fictional, the story has historical echoes. The real-life marriage of Princess Bernice Pauahi Bishop, a great-granddaughter of Kamehameha I who owned vast amounts of land, and Charles Reed Bishop, an American businessman, may have provided the inspiration for the King family. The family history is interwoven into the main plot of the film, the dynamics and drama of a family that has somehow grown apart and struggling to deal with their mother’s accident.

During a visit with Elizabeth’s doctor, Matt discovers that Elizabeth is in a persistive vegetative state, and that her living will dictates that she must be taken off life support. The doctor advises Matt to give family and friends time to say goodbye before Elizabeth dies. Matt takes Scottie to bring Alex home from the Hawaii Pacific Institute. When he tells Alex that her mother is going to die, she reveals that Elizabeth has been having an affair with another man. Matt’s reactions to all this news include an emotional trip to Kauai, where he and his daughters also visit the family land and reminisce about past camping trips. The pristine beauty of the King land is contrasted with shots of development on Kauai, particularly resorts and golf courses, the fate that awaits the trust land. In the end, Matt has a change of heart and refuses, as the sole trustee, to sell the land. Explaining himself to his angry cousins, Matt declares, “We didn’t do anything to own this land, it was entrusted to us,” and if they sell it, “something we were supposed to protect is gone.”

The process of coming to terms with the death of his wife forces Matt to confront what is owed to the dying, the dead, and to those who remain behind. It is perhaps Matt’s failure to prevent his wife’s death that makes him cling to his role as steward of the land and the family’s Hawaiian legacy. In an odd parallel, Matt acts as the steward of both Elizabeth’s death and the King land – as he lets one go, he appreciates the importance of the other all the more. As Elizabeth’s death brings him closer to his children, it also brings him back in touch with his past and the importance of preserving his family’s legacy for future generations.

It is slightly disappointing that the film never really engages with the history of Hawaii and never really links the two plots very well. The King family is, as Matt puts it, “haole as shit,” (haole is the derogatory term for white immigrants); sending their children to Punahou School and living lives of privilege and ease. The Punahou School was one of two elite schools founded by American missionaries in the islands, and was initially a school for the children of the missionaries. The other was the Chiefs’ Children’s School, a school for the children of high-ranking Hawaiians, which the last five Hawaiian monarchs attended. Punahou, as Sarah Vowel notes, became known as the “haole rich kid school,” labeled by President Obama, an alumnus, as an “incubator for island elites.” That the King family attended Punahou clearly marks them as island elites, participating in a haole educational tradition that stretches back over a century and a half.

Because the King land, moreover, comes from the marriage of a fictional Hawaiian princess and American businessman, the film does not have to address the relationship between land ownership and the role American missionaries and their descendants played in paving the way for American annexation of the islands, and why so much of Hawaii ended up in the hands of American settlers and their descendants. Traditionally, Hawaii’s land was divided according to a hierarchical system of reciprocity. As historian J. Khaulani Kauanui notes, chiefs divided up land amongst lesser chiefs, who allocated land to stewards, who administered the access to land of the commoners, who worked the land, sending tribute back up the ladder, ending with the king himself. In 1848, however, shortly after the creation of a constitutional monarchy, King Kamehameha III was persuaded to divide up the land not belonging to the Crown into individual plots, to be claimed by Hawaii’s commoners, an act known as the Mahele. As with the Dawes Act, the Mahele was hailed as step that would lead to Hawaiians becoming independent yeoman farmers, owners of their own plots of self-sustaining land. What happened in reality, also in striking similarity to the legacy of the Dawes Act, is that land once held communally and for the common good was concentrated in predominantly white hands, leaving the native population with a fraction of their former lands.

The backdrop to the Mahele was the precipitant drop in Hawaii’s native population since the late 18th century, due mainly to diseases introduced by European and American sailors and missionaries. The declining native population (the 1890 census listed just over 30,000 native Hawaiians, a drop of over 90% of the estimated population at the end of the 18th century), as well as the failure to educate Hawaiians about the new land policies and the difficulty of filing claims for land, meant that only a small fraction of the land put up for sale went to Hawaiian commoners. This was compounded by an 1850 law allowing the government to sell unclaimed land to anyone, foreigners included, and an 1874 law privatizing mortgage foreclosures, all of which led to, by 1890, haoles controlling ninety percent of Hawaiian land.

At the same time, the booming demand for foodstuffs created by the Gold Rush in California and Oregon, and the growing market for Hawaiian sugar in the northern United States after the Civil War cut off the supply from Louisiana, led American planters, many of them grandchildren of the original missionaries, to come to the islands, to expand their operations and buy up as much land as they could to grow their valuable crops. The introduction of a constitutional monarchy in which haoles eventually made up the entirety of the judiciary and much of the government, moreover, legally reinforced American notions of private ownership. These changes created a perfect storm for American planters to overthrow the monarchy. As their wealth and influence grew, the interests of the planters were set on a collision course with the interests of the Hawaiian monarchy and Hawaiian national sovereignty. And when America began casting about for an overseas empire in the waning years of the 19th century, there the islands were, already settled by a substantial American population (or at least the descendants of Americans), which had overthrown the Hawaiian monarchy and was eager to be annexed by the United States. Hawaii was a move-in ready Pacific colony, prepared by the labors of American missionaries and their descendants, the American planters, for annexation.

Ultimately though, while “The Descendants” is a Hawaiian story, it is not a film about Hawaii or Hawaiian history. And it is not historical fiction, though the fictionalized history of the King family plays a strong supporting role. It is a film about everyday human tragedy, and the ways we cope with loss, grief, anger, betrayal, and the fact that nothing we love stays the same forever; that families fall apart and come back together, that land is subdivided and over-developed, that traditions are lost, and that we have to do our best to adapt and draw our own conclusions about what is owed to both the past and the future.

For more on Hawaiian history, we recommend:

J. Khaulani Kauanui, Hawaiian Blood: Colonialism and the Politics of Sovereignty and Indigeneity (Durham: Duke University Press, 2008).

Sarah Vowel, Unfamiliar Fishes (New York: Riverhead Books, 2011).

Photo credits:

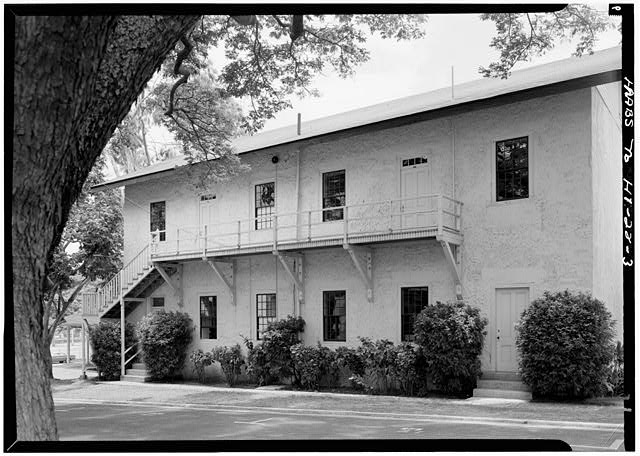

“EAST (REAR) ELEVATION – Punahou School, School Hall, 1601 Punahou Street, Honolulu, Honolulu County, HI.”

Courtesy of The Library of Congress

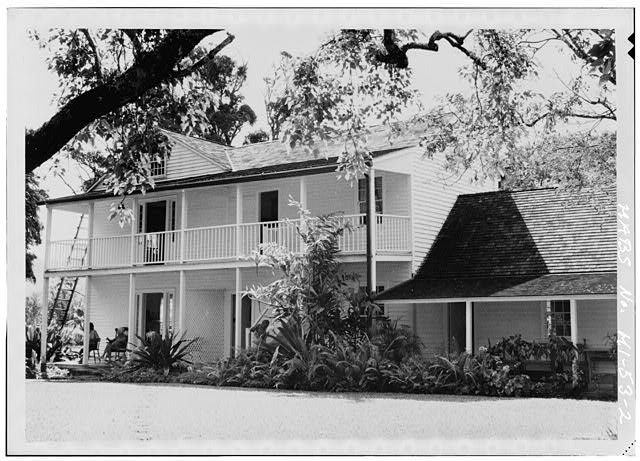

“FRONT ELEVATION, ANGLE VIEW – Waioli Mission House, Kauai Belt Highway, Hanalei, Kauai County, HI.”

Courtesy of The Library of Congress

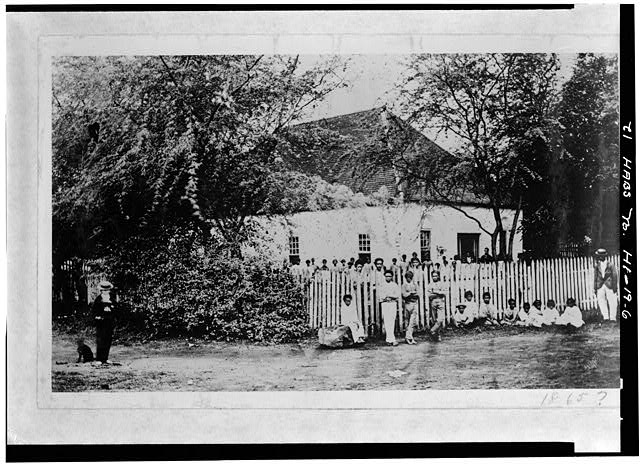

“GENERAL VIEW, ca 1865 (From original photograph in Hawaii State Archives. Photocopy made for HABS in 1966). – Adobe Schoolhouse, Kawaiahao Street at Mission Lane, Honolulu, Honolulu County, HI.”

Courtesy of The Library of Congress