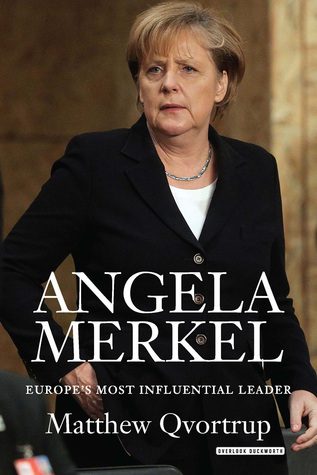

With a sly smile, Vladimir Putin, President of Russia, lets his black Labrador Koni off the leash and it immediately begins to approach German Chancellor, Angela Merkel. Merkel, who was bitten by a dog in 1995, attempts to hide her visible discomfort, lips pursed and legs tightly crossed. Putin, well aware of the effect he created in the German Chancellor, appears smug and amused. The first Putin-Merkel visit in 2006 got off to a rough start. As one of many revealing anecdotes in Angela Merkel: Europe’s Most Influential Leader, political scientist and professor Matthew Qvortrup seeks to introduce an American audience to the woman fondly known in Germany as “Mutti.” Qvortrup’s work remains one of the few English language biographies of “the new leader of the free world.” Serving as the Chancellor of Germany since 2005, Merkel represents the Christian Democratic Union (CDU), the major center-left party in Germany. On September 24, 2017, Merkel won a remarkable fourth term in office, heading off a nationalist surge to maintain control of the German Bundestag, the legislative body at the federal level in Germany. Merkel’s success begs the question: how did a woman, born in relative obscurity in East Germany to a Lutheran pastor rise to become the protégée of Helmut Kohl and arguably the most powerful woman in Europe? Qvortrup, relying on original sources and archives never made available in English, in combination with his powerful storytelling abilities, creates a compelling narrative of Merkel’s rise.

With a sly smile, Vladimir Putin, President of Russia, lets his black Labrador Koni off the leash and it immediately begins to approach German Chancellor, Angela Merkel. Merkel, who was bitten by a dog in 1995, attempts to hide her visible discomfort, lips pursed and legs tightly crossed. Putin, well aware of the effect he created in the German Chancellor, appears smug and amused. The first Putin-Merkel visit in 2006 got off to a rough start. As one of many revealing anecdotes in Angela Merkel: Europe’s Most Influential Leader, political scientist and professor Matthew Qvortrup seeks to introduce an American audience to the woman fondly known in Germany as “Mutti.” Qvortrup’s work remains one of the few English language biographies of “the new leader of the free world.” Serving as the Chancellor of Germany since 2005, Merkel represents the Christian Democratic Union (CDU), the major center-left party in Germany. On September 24, 2017, Merkel won a remarkable fourth term in office, heading off a nationalist surge to maintain control of the German Bundestag, the legislative body at the federal level in Germany. Merkel’s success begs the question: how did a woman, born in relative obscurity in East Germany to a Lutheran pastor rise to become the protégée of Helmut Kohl and arguably the most powerful woman in Europe? Qvortrup, relying on original sources and archives never made available in English, in combination with his powerful storytelling abilities, creates a compelling narrative of Merkel’s rise.

The first half of Angela Merkel details both the solidification of Merkel’s power in the CDU, but also the solidification of Merkel’s “brand.” As she herself would admit, Merkel relies far more on substance and consistency than flashy speeches and charm. Political pundits in Germany and abroad often criticize Merkel as “boring.” She prefers to exude calm, rationality, prudence, and unflappability. For much of her early life, says Qvortrup, Merkel “was not consumed by a passion for dissent,” instead nurturing a deep love of the sciences, eventually achieving a doctorate in quantum chemistry. Qvortrup attributes Merkel’s political awakening to the collapse of the Soviet Union and the process of German reunification. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, Merkel became involved in the new democracy movement through the Demokratischer Aufbruch (DA), which would eventually merge with the East German CDU. Merkel rapidly rose through the ranks, eventually receiving an appointment by Kohl himself as federal Minister for Women and Young People. Merkel’s early years coming up in the ranks of the CDU solidified in her mind the important of grassroots organization, effective team members, and loyalty to the party hierarchy. While Merkel discovered her commitment and passion on issues of capitalist oriented economic development and reunification, Merkel also revealed a political pragmatism many of her colleagues did not initially suspect. According to Qvortrup, Merkel proved perfectly willing to let other members of the party fail if it advanced her own progress. Early on in her career in November 1991, Merkel declined requests to speak out in favor of the Prime Minister of the German Democratic Republic (DDR), Lothar de Maizière, after calculating that his fall opened the door for her career advancement.

Angela Merkel at a Christian Democratic Union (CDU) campaign event in 2013 (via Wikimedia Commons)

The second half of Qvortrup’s work really picks up speed as Merkel, after consolidating power in the CDU, gains control of the chancellorship. Here, Qvortrup launches into the crux of his argument: Merkel’s success, he believes, rests in her unique ability to recognize others’ perceptions of her, and then either reinforce or upend them as needed. This, in combination with her pragmatism, willingness to compromise on the international stage, and promotion of modernization and globalization at home, made Merkel not only popular, but effective. Her sole guiding principle, it seems, is the preservation of European unity with Germany’s preeminent position in it. In Qvortrup’s calculations, Merkel’s handling of almost every major political crisis, from the Eurozone crisis to Russian aggression in Ukraine, reflected her ability to calmly and rationally assess the situation. Her interactions with Putin are perhaps the most famous and powerful example of her rationality. According to Qvortrup, Merkel manipulated Putin’s expectations of her as a matronly, unassuming woman in order to drive concessions out of him, and put herself in his situation. As an East German, Merkel possessed a unique ability to recognize the Russian geopolitical uncertainty. Furthermore, Qvortrup hints at the clear gender politics of much of Merkel’s reign: she not only remains above the fray in the masculine political games of Europe’s male leaders, but she also manipulates their expectations of her.

Merkel arrives at the Supporting Syria and the Region conference, London, 2016 (via Flickr)

Qvortrup ends with his most interesting discovery of all: Merkel’s support for refugees represents a stark departure from her usual approach to politics. Merkel, traditionally governed almost entirely by pragmatism and a commitment to a united Europe, finally “discovered an issue that was more important than her own career.” Here, Qvortrup comes full circle to the young girl who grew up in a divided nation, finally finding an issue on which she is willing to expend her political capital and stake her own reputation. Angela Merkel offers an insightful, enjoyable read to those seeking to understand the woman Qvortrup describes as part Mother Courage, part Machiavelli.

Also by Augusta Dell’Omo on Not Even Past:

History Calling: LBJ and Thurgood Marshall on the Telephone

Review of Trauma and Recovery by Judith Herman

You may also like:

Joseph Parrott reviews Churchill: A Biography by Roy Jenkins

Jeremi Suri on his new book The Impossible Presidency

Great Books in Women’s History: Europe