Ōura Kei’s name is not widely known outside Japan, but she was one of Nagasaki’s most famous residents. One of the Japan’s first exporters of green tea, Ōura has become known as one of her home city’s three “heroic women” (女傑, joketsu), who are celebrated for their exploits during Nagasaki’s treaty port period, which spanned from 1858 to 1899. (Another of Nagasaki’s heroic women, physician Kusumoto Ine, has already been profiled in Not Even Past.)

Despite Ōura’s prominence as a historical figure, the documentary record she left behind is sparse, limited to information about some of her business activities and one particularly infamous fraud case. Because of this, research around Ōura’s life has primarily focused on her role in the tea trade and her struggles as a merchant and a woman in a system that was stacked against her. However, while conducting archival research in Nagasaki, I discovered something new: two international marriage petitions from 1883 that list her as a go-between for the marriages of young Japanese girls and older Chinese men. These petitions show that trade, and the social networks it produced, extended far beyond the import and export of physical goods. Taken into consideration with what we already know about Ōura Kei’s life, these petitions also reveal the way that unequal power dynamics were often an inextricable part of life in treaty port Nagasaki. As a successful merchant, Ōura Kei was deeply embedded in the transnational communities of the city, and she was both subject to and an enabler of the hierarchies they were built on.

Making (or Stealing) a Fortune in Treaty Port Nagasaki

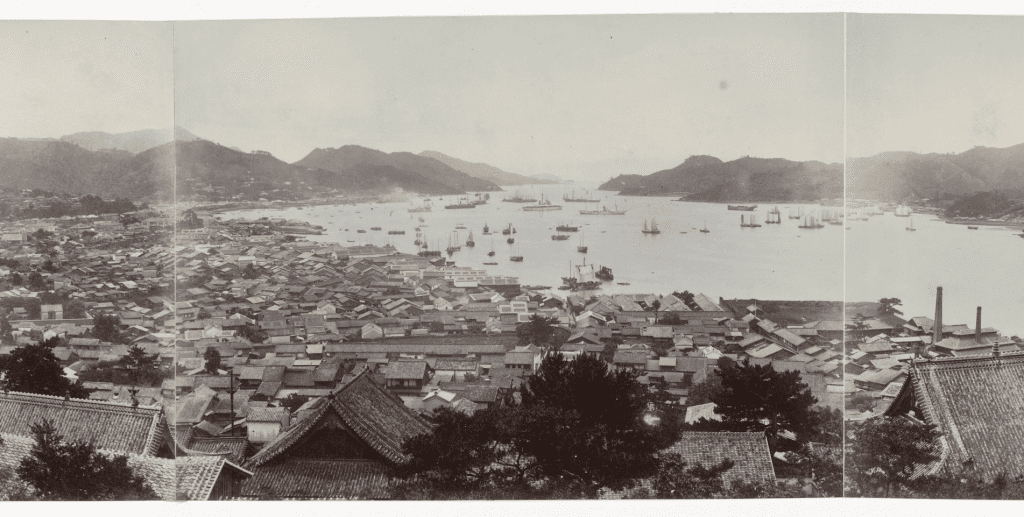

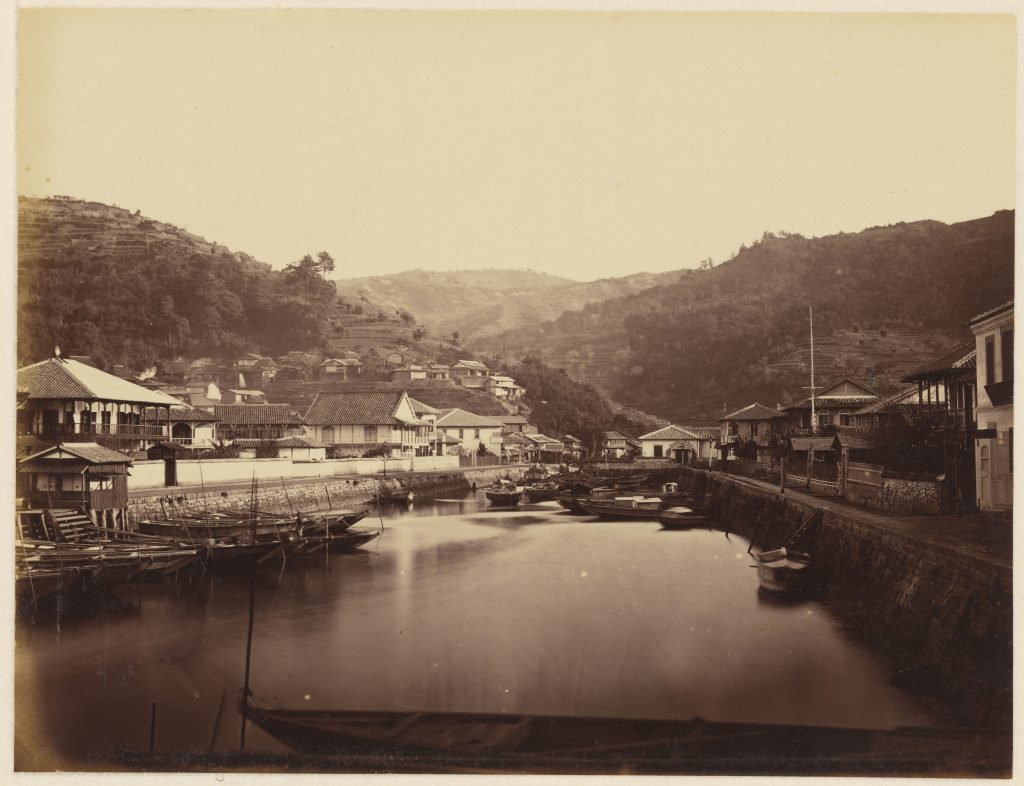

Nagasaki was one of dozens of treaty ports in East Asia opened in the second half of the nineteenth century. The first treaty ports were the result of the unequal treaties signed between the Qing and British empires after the end of the first Opium War in 1842, which defended the right of British merchants to import opium into China under the banner of free trade. Those treaties became a model for diplomatic relations between American and European treaty powers on the one hand and East Asian governments on the other for most of the rest of the nineteenth century. In the case of Japan, the unequal treaties signed in the 1850s ensured that European and American residents of Japanese treaty ports were not subject to Japanese law, could rent property indefinitely within a designated foreign settlement, and were free to engage in trade (often tariff-free) with anyone that they wanted.

These rights were protected not just by consular representation but also by the threat of gunboats and violent reprisals. Nagasaki had been an international entrepot for centuries before becoming a treaty port. In the seventeenth century, Japanese authorities retained almost total authority over European residents like the Dutch. The situation was reversed in the nineteenth century.

Elites who, in various factions and under different governments, remained in power locally and nationally throughout the early decades of the treaty port period. The clash of older domestic and new international hierarchies within Nagasaki created a dynamic environment for both opportunity and exploitation.

Ōura Kei was already thirty and the head of her merchant family when Nagasaki became a treaty port in 1858. Due to a rash of personal and professional losses, the Ōura family business was on the brink of bankruptcy, and the timing of the treaties could not have been better. The new treaty provisions meant that any merchant family, not just those designated by the ruling Tokugawa shogunate, could engage in international trade. Ōura took immediate advantage of this new freedom, abandoning her family’s old trade in rapeseed oil and venturing out into the surrounding countryside for samples of tea that she could sell to foreign merchants. Her enterprising work paid off when William Alt, one of the first English merchants to arrive in the treaty port, placed an order for 10,000 kin of tea (almost 1,300 pounds). Ōura and her employees, with no pre-existing agreements with local tea farmers, had to scramble to fulfill the order, buying a few pounds here and there across multiple farms from many different villages.[1] Ōura built on that first success to become one of the richest traders in Nagasaki, rebuilding her family home in the heart of the trading district into a beautiful compound renowned for its gardens.[2]

The international trading boom that fueled Ōura’s fortune did not last—at least not in Nagasaki. In the early 1870s, after the Tokugawa shogunate was overthrown by Japan’s new Meiji government, the most lucrative international trade moved to the more centrally located treaty ports of Yokohama and Kobe, endangering the prospects of all merchants left behind in Nagasaki. In this moment of economic vulnerability, Ōura was caught up in a serious fraud case. Tōyama Ichiya, a samurai from Kumamoto prefecture, using forged documents, convinced her to stand as surety for a 3,000 ryō advance he negotiated with the English trading company Alt & Company in exchange for a delivery of Kumamoto-grown tobacco.[3] 3,000 ryō was a significant sum, somewhere in the range of $60,000 today.

Instead of securing the tobacco, Tōyama used the advance to pay back previous debts with another foreign merchant house and then ran away. Ōura and Henry Hunt, Alt & Company’s Nagasaki representative, spent months trying to chase him down. Ōura in particular was relentless, demanding the attention not only of Kumamoto officials but also the head of Tōyama’s clan, prompting at least one samurai to scold her for behaving “well outside appropriate boundaries.”[4] Despite this critique, it is clear from the surviving documentation on the Tōyama Incident that Ōura was consistently taken seriously as a merchant by both foreign firms and Japanese officials, and there is little evidence of gendered discrimination. She was referred to in the surviving documents exclusively as “the merchant Ōura Kei (商人大浦敬, shōnin Ōura Kei),” when it was much more common at the time in official documentation to refer to women in any social position with the character for women (女, onna) first, followed by their occupation or name.

In fact, in Japanese-language documents, Ōura is the only person to gender herself, and she does so strategically. In a letter to Nagasaki prefectural authorities, asking them to investigate, she claimed that it was “with the shallow intellect of a woman (joshi no asai chi,女子之浅智)” that she had put her seal on the contract with Tōyama. Since the documents surrounding the case in fact reveal the opposite, that it took considerable effort for Tōyama to dupe her, this was likely an attempt to get Nagasaki officials to treat her sympathetically and hopefully absolve her guilt.[5]

Ultimately, Tōyama could not provide the promised tobacco or return the advance, and Alt & Company finally brought the matter to court. In this official setting, Ōura Kei was at a disadvantage not as a woman but as a merchant, without special legal protection or well-placed advocates. The foreign trading firms caught up in the case could not be held responsible under Japanese law for receiving illicit, stolen money, and the English consul acted as an aggressive advocate for Alt & Company throughout the investigation and trial, urging the Nagasaki government repeatedly for a fast settlement rather than a just one.[6] The samurai involved (with the exception of Tōyama Ichiya) were protected by their status in Japanese society and at times actively aided by their peers in the Nagasaki and Kumamoto prefectural governments. For example, low-ranking samurai and translator Shinagawa Fujijūrō, a creditor of Tōyama’s who helped broker the deal with Alt & Company and was later paid with the same advance, avoided criminal charges completely after returning his share of the stolen money. Tanaka Kinbei, a merchant whose son’s seal Tōyama had used to create a forged document without his knowledge, was sentenced to sixty days in jail.

Without the privileges of the samurai status, Ōura Kei was at a disadvantage under both treaty-enforced and domestic power hierarchies, and there was no one in power to advocate for her. In the end, she was cleared of all wrongdoing, but she was still held liable for around half of the advance that Nagasaki officials could not otherwise recover. Given the sums involved, this was a significant loss in an already economically fraught time.

Even after this verdict, Ōura is often seen as a defiant figure in Nagasaki history, battling prejudice to succeed in the face of significant discrimination. Her name on newly discovered marriage petitions adds a wrinkle to this perception, however, as they reveal Ōura not only as a victim, but also as an enabler of unequal power relations.

Both a Merchant and a Marriage Broker

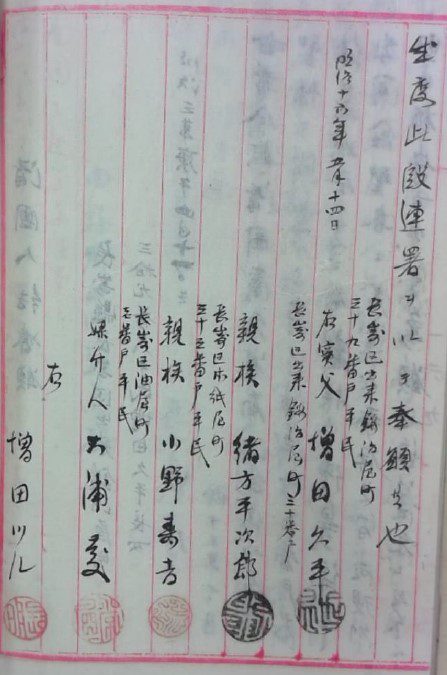

Despite what Puccini’s Madame Butterfly would have you believe, we don’t know much about the ways in which international marriages were arranged in Nagasaki during the treaty port period. Official international marriages, which only became legal in 1873, required the head of household—the woman’s father or brother—to petition the Japanese government for permission. Even after it was made legal, official marriages represented only a small fraction of the international intimate relationships within the treaty port, most of which were informal and transactional relationships that were easy to dissolve. The surviving marriage petitions, collected in the Register of Contracts with Foreigners (内外人契約の部, Naigaijin keiyaku no bu) provide historians with important demographic data for understanding international marriage, but they do little to explain how the interested parties were introduced, what their previous histories were, or what happened to them after the petition was submitted.

Ōura Kei’s involvement in at least two marriages therefore provides important clues as to the nature of go-betweens and how they functioned in Nagasaki. Go-betweens—or the official acknowledgment of them in government records—were never very common. Only about 40% of marriage petitions from 1873-1886 listed a go-between, and their inclusion in petitions all but died out by the 1890s. Most go-betweens, like Ōura, were only registered on one or two marriage petitions, which indicates that they were not professional go-betweens, but instead connected foreign residents and Japanese women through pre-existing personal or professional networks. This is reinforced by the strong geographic tie between a go-between and the Japanese household requesting permission. Japanese women who married foreign men came from all parts of the city, and go-betweens almost always registered an address from the same neighborhood as the prospective wife. As a merchant, Ōura Kei was deeply embedded in the international trading market of Nagasaki, and that is likely the network she used when connecting the parties for these marriages. We don’t have enough evidence to say that all go-betweens in Nagasaki were somehow involved in mercantile activities, but there were few things that bridged inter-communal networks more effectively than trade in a treaty port.

The specifics of the marriages that Ōura arranged highlight the inequities that were inherent to even interpersonal intimate relationships within the treaty port. The two girls registered in the 1883 marriage petitions, Masuda Tsuru and Koyanagi Tomi, were only fourteen years old at the time of their marriage, and one of the prospective Chinese husbands was at least forty.[7] The girls were well below the average age of marriage in Japan at the time, and almost seven years younger than the median age of other women who petitioned to marry foreigners in Nagasaki (21.5 years old).[8]

Younger marriage for women was more common in the Qing Empire, where a demographic crisis made it difficult for large numbers of men to find wives, but extreme age differences between spouses were not inherently more normalized. There is no question that these two marriages were legal—there was no civil code yet, and when it was passed it only required women under 25 to have the permission of their household head to marry. Women at the time were considered legal dependents of their household head, be it their father, brother, or husband, so this large age gap would have only enhanced already existing social and legal power imbalances between these girls and their eventual husbands.

We do not know what happened to these girls, but their marriages would have had immediate consequences for their nationality and their ability to move freely in the city. All Japanese women who married foreign men lost their claim to Japanese nationality and were removed from their natal household register. This aspect of Meiji international marriage law was based on the French legal code and was a common provision internationally. Masuda and Koyanagi legally became Chinese subjects while still living in their hometown. Because Nagasaki was a treaty port, that meant that they were not allowed to live in the Japanese part of the city, and they had to live in the foreign settlement even when their husbands were away.[9] It is also unclear how long they would have stayed in Nagasaki. While Chinese residents were far more likely to settle semi-permanently in Nagasaki than European or American residents, the Sino-Japanese War in 1894, just over a decade after the marriage, caused a mass migration of Chinese residents back to China. Masuda and Koyanagi, now twenty-four, would likely have followed their husbands if they had not already left, moving out of the range of the support of their natal familial networks and the sphere of Japanese consular protection. Once gone, it was often difficult for families to maintain contact, especially after the death of the husband.[10]

Ōura Kei spent most of her adult life navigating social networks and official systems that were shaped by opposing and unequal power dynamics. During the Toyama Incident, as a Japanese merchant pitted against treaty-protected foreign merchants and domestic elite, she was at a disadvantage on multiple fronts. When she helped arrange Masuda Tsuru and Koyanagi Tomi’s marriages, however, she was a wealthy and influential local figure at the center of an extensive trading network. In this position of relative power, she facilitated deeply unbalanced marriages of two young girls to men three times their age.

These newly discovered marriage petitions serve as a reminder that in treaty port Nagasaki, where opportunity and exploitation went hand in hand, there was no easy distinction to be made between powerful and powerless, oppressor and oppressed, advantaged and disadvantaged. Ōura Kei was not a villain, and she was not a hero; she was an ambitious, driven woman who fought for everything she had and did not hesitate to use the power that she had earned. Her life and its complications helps us understand that inequality was not the exception in treaty port Nagasaki, it was embedded into almost every aspect of everyday life.

Archival Sources:

Nagasaki Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Naigaijin Keiyaku no Bu (1873-1895), ID 14 364-3 to 14 567-2. Nagasaki Museum of History and Culture.

Nagasaki Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Tōyama Ichiya ikken Meiij gonen dō rokunen, ID 14 338 12. Nagasaki Museum of History and Culture.

Published Sources:

Honma, Yasuko. Ōura Kei joden nōto. Nagasaki-shi: Honma Yasuko, 1990.

Kawaguchi, Yoko. Butterfly’s Sisters: The Geisha in Western Culture. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010.

Koga, Jūjirō, Maruyama yūjo to tō kōmōjin. Nagasaki, Nagasaki Bunkensha, 1968.

Lundh, Christer, and Satomi Kurosu. Similarity in Difference: Marriage in Europe and Asia, 1700-1900. The MIT Press Eurasian Population and Family History Series. Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press, 2014.

Shigefuji, Takeo. Nagasaki kyoryūchi bōeki jidai no kenkyū. Tōkyō: Sakai Shoten, 1961.

[1]. Ōura Kei, Seicha no bu Meiji 17nen, ID 17 224-2-2, Nagasaki Museum of History and Culture.

[2]. For more information about Ōura’s early life, see Honma Yasuko, Ōura Kei joden nōto (Nagasaki-shi: Honma Yasuko, 1990).

[3]. The company the advance came from, Alt & Co, was founded by the same William Alt who bought Ōura’s first shipment of tea, but he sold the business and left Japan in 1871.

[4]. Nagasaki Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Tōyama Ichiya ikken Meiij gonen dō rokunen, ID 14 338 12, Nagasaki Museum of History and Culture. A printed copy of some documents can also be found in Shigefuji Takeo, Nagasaki kyoryūchi bōeki jidai no kenkyū (Tōkyō: Sakai Shoten, 1961).

[5]. Ōura Kei reprinted in Shigefuji, p. 233.

[6]. On June 11th, 1872, ten months before the final verdict was given, the English Consul Marcus Flowers wrote, “I understand Mrs. Ora Kei has sufficient means, and as it was solely and entirely upon her guarantee that the money was advanced upon this contract, I must beg you will kindly press her for immediate payment.” Nagasaki Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Eikoku Ōrutoshōkai yori, ID14-219-6, Nagasaki Museum of History and Culture.

[7]. Item 9 and 21 in Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Naigaijin keiyaku no bu, 1883, ID 14 467-2, Nagasaki Museum of History and Culture.

[8]. Nagasaki data is drawn from the marriage petitions found in the Naigaijin keiyaku no bu. For more information on Meiji marriage demographics, see Carl Mosk, “Nuptiality in Meiji Japan,” Journal of Social History 13(3) (Spring, 1980), p. 479.

[9]. There was a “health” clause by the late 1880s that any foreigner could use to stay temporarily outside of the foreign settlement. On at least one occasion, the British consul invoked this right on a Japanese woman’s behalf when her original petition to live with her family while her husband was abroad was denied. British Consulate, December 16, 1889, Raikan, Nagasaki Museum of History and Culture.

[10]. One father whose daughter left for China with her husband mentions trying to contact his daughter fourteen times without response. “My wife, Sada’s mother, is filled with melancholy morning and night and cannot eat or sleep,” he wrote. Item no. 7 in Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Naigaijin keiyaku no bu, 1880, ID 14 453-2, Nagasaki Museum of History and Culture.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.