By Jesse Ritner

Passing Red Hill, we turned onto Colorado Route 133. Ahead of us towered Mount Sopris, an almost 13,000 foot volcano. 133 shoots towards the Elk Mountain Range, a row of peaks frequently topping 12,000 feet, but Sopris still looks immense in comparison. Casting its shadow over the quaint town of Carbondale, it sits alone, topped with scree and rock glacier, strikingly grey in a valley dominated by reddish cliffs, aspens, fir, and spruce. For those in the Roaring Fork Valley, hiking Sopris is a right of passage. It is steep, exposed, and offers sweeping views. But we were not driving to Sopris, we were heading around it.

The Roaring Fork Valley is one of the most popular tourist spots in the country. At its northern end (down valley) sits Glenwood Springs, an old resort town which has sprawled out from its century old hotel and bathhouse. On the southern end lies the exclusive town of Aspen (up valley), where million dollar houses and multi-million dollar mansions nestle themselves into the small box canyon at the base of the world famous ski resort. For its part, Carbondale and its dormant volcano lie roughly between the two.

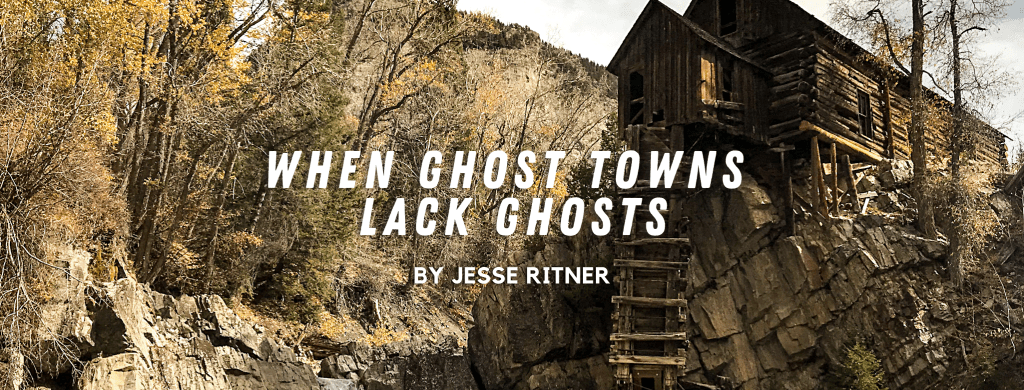

Carbondale is in the widest part of the Roaring Fork Valley, but behind Sopris lies a narrow stretch of road which runs alongside the perfectly clear Crystal River. So far unscathed by the wildfires which have blistered the state in recent years, Route 133 leads to a number of small mining towns. Hidden in the narrow valleys of the Rocky Mountains, these old towns and ghost towns litter the national forests which cover much of Colorado State. They once sat on the ends of a maze-like rail system that brought their wares from the scraggly valleys, out to larger valleys, like the Roaring Fork, and back east towards Denver, where their precious metals were distributed to distant parts of what is now the continental 48. But with time, these trainlines disappeared.

Today what remains behind Sopris is a winding road, taking up the little remaining space between the Crystal River and the tall mountains it weaves through. Carbondale, Redstone, and the town of Marble, which sit alongside the river, are all places to see as much as they are places to live, and all are named for the materials they mined.

We were going to a now uninhabited town. Marble is 28 miles down 133. In a tiny valley, with a population of around 100 people, the small houses feel isolated and alone. The town lays on a large deposit of sparkling white marble utilized in monuments throughout the country. (The most famous of these are the Lincoln Memorial in Washington D.C. and the Tombs of the Unknown in the National Cemetery in Arlington, Virginia.) Marble was reborn in the late twentieth-century with summer tourism, sculpting symposiums, and as a hub for backcountry skiing. We drove through the little town, were we saw shiny white statues strewn around, and small art galleries selling the unique sculptures made by local artists. Marble is small, but it is also full. Life continues and adapts, and the town, in its peculiar way, seems to thrive. But the small town of Crystal, only five miles past Marble, suffered a different fate. Crystal, like many other sites in Colorado, is now known as a ghost town.

Crystal is famous for the Crystal Mill (also known as the Lost Horse Mill and the Sheep Mountain Powerhouse). Photos and paintings of the building dot the Roaring Fork Valley, adorning the walls of exclusive restaurants and unaffordable art galleries in Aspen. But its location is a bit more mysterious. Most people who visit the resort never make their way to the town, preferring the closer locations of Independence and Ashcroft, which each sit a short fifteen minute drive from downtown.

For those seeking ghosts, the decision makes sense. In Ashcroft and Independence the Aspen Historical Society has spent decades carefully preserving ruins. The towns feature wooden footprints, and semi-rebuilt houses and hotels, all of which are carefully crafted and preserved to appear as if they are still in a state of disrepair. These towns are meant to educate the general public, and they reflect this goal in their signage. Little plaques share facts about the often shockingly large size of these boomtowns at their peak, the multiple newspapers each housed, and the impressive amount of wages spent on alcohol. The plaques also feature other forms of information. They explain the environmental impacts of mining and ranching, the current attempts to revive lost or disappearing species, and what can best be described as fun-facts about Ute Indians.

There is no mention of violence in this selective retellings. While the informational readings at times allude to drunken brawls and crowded jailhouses, Indigenous removal, collapsed mines, and racial violence all seem to pass unnoticed. The ghost towns lack agency and they lack historical actors. It is as though the entire towns were imagined in the passive voice, sitting quietly as national and global changes exerted their will on the rotted wood, rusted metal, and the ghosts of people who presumably wander their streets at night. Of course, that is the purpose of a ghost town. They serve as passive observers of the present, from a past we cannot completely know.

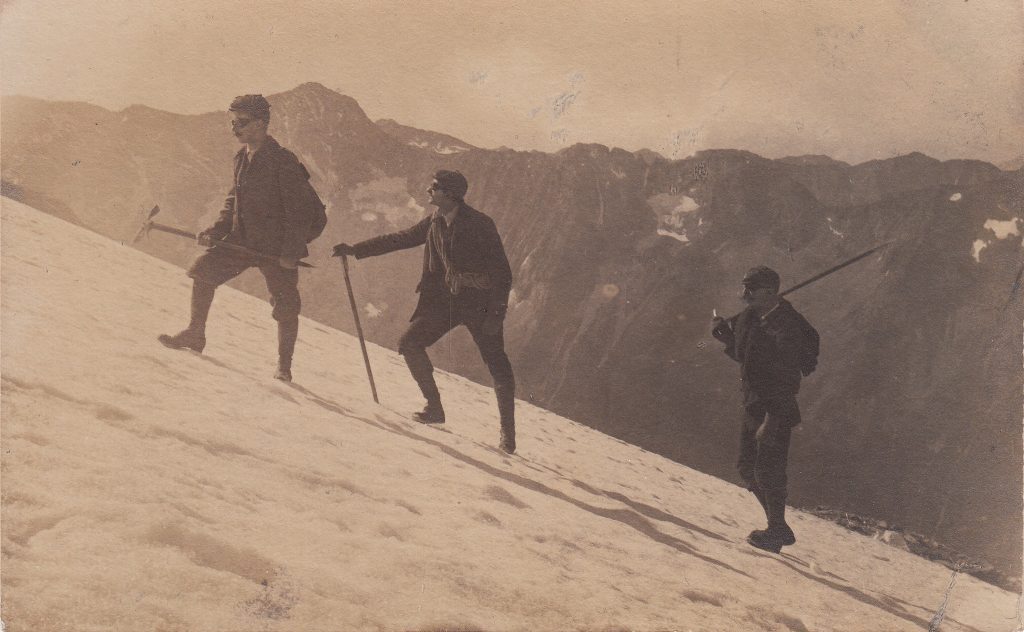

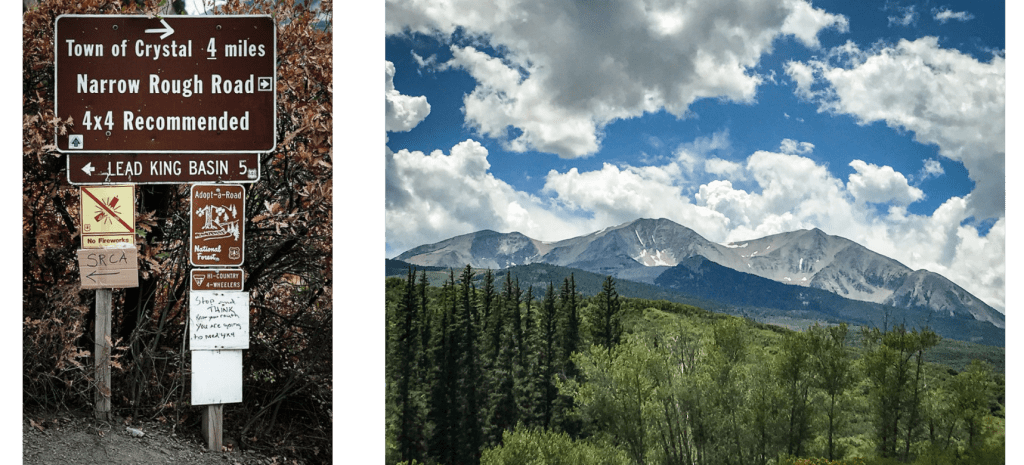

We had already visited Ashcroft and Independence, but our trip to Crystal was different. First and foremost, it is difficult to drive to Crystal. With an ATV or a high clearance vehicle you can slowly make your way up the rocky dirt road which begins on the edge Marble. But my Subaru Crosstreck was not up to the challenge. So, we parked, and we walked. The first mile or so ascends almost 1,000 feet, but the views are worth it. For those of us who crave the narrow valleys and steep accents of the Rocky Mountains, the views of aspens and the soft rapids of the crystal river, today as they did one-hundred-and-fifty years ago, offer stunning views. That settler-colonists moved into this remote part of the country felt increasingly reasonable as we made our way down the bumpy and winding road. After about three hours of hiking, the road made its final curve to the left, and as we came around the bend the mill emerged in front of us, only about fifty yards away.

Although it is a ghost town, Crystal was never truly abandoned. Several people still live there every summer, preserving some buildings and giving the town life. It was first settled in the 1860s almost 20 years before the White River War removed the Ute from the Region. And in 1880, following the war, it was finally legally incorporated. Like many others, Crystal sat near rich deposits of silver, lead, and zinc. But it was always small. At its height it only boasted 500 people, making it much smaller than Ashcroft and Independence, which each housed over a 1,000 people. The town was always difficult to access. In fact, it was so remote that without Norwegian snowshoes (skis) it was almost impossible to reach in the winter, when deep snows covered the roads to Marble and Crested Butte.

Notably, the town of Crystal feels different than Independence or Ashcroft. And much of that feeling comes from the mill. The mill perches precariously on a low bluff overlooking the Crystal River. From the way it sits, the wooden building appears to be a strong wind away from toppling down into the water below. But it also broadcasts a type of strength. Unlike Ashcroft and Independence, with their well-preserved deterioration, the mill is strong, built on thick timber, and clearly built to last. Which, of course, it has done. Where Independence and Ashcroft are largely in ruins, the wooden mill and the town preserved behind it are relatively unscathed. The mill is an entity in and of itself. It has no need for the town. With its horizontal turbine, which once drove air compressors for machinery at the nearby mines, the mill struck us unlike anything else we had seen.

The mill, and the town of Crystal which sits just around the bend, are unique, in that they are privately owned. The result is a town without any signage. Neither plaques or boards claim to know the history or present the truth. Instead, the mill just sits, posing for onlookers like us who gawked at this quietly celebrated gem. While Ashcroft and Independence haunt, Crystal and the mill invited us in. Rather than imagining past people wandering the street – it only has one street these days – we saw beautiful log cabins which stood proud, strong, and ready to be lived in.

It is almost a truism in historic preservation that the best way to preserve a building is to use it. While buildings wear and tear, frequent use allows people to see the deterioration, and to fix it and adapt to it. These buildings are cyborgs. The old parts are replaced with new ones, and the materials are occasionally discarded for newer – “better” – technologies. In this way, they are not much different than people in a sci-fi flick, where eyes are metal and arms turn magically into weapons. But these buildings are full of life. They are not simply observers. These buildings live, they breath, and as a result, the town feels alive, free from the ghost that haunt nearby towns.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.