Since its creation in 2010, Not Even Past has published a wide range of resources connected to Black History written by faculty and graduate students at UT and beyond. To mark Black History Month, we have collected them into one compilation page organized around 11 topics. These articles showcase groundbreaking research, but they are also intended as a concrete resource for teachers and students. This is an evolving compilation that is continually updated.

This list was originally compiled by Alina Scott and Gabrielle Esparza. It was subsequently added to by Atar David.

Topics

- Economy of Slavery

- Slavery & the Family

- Urban Slavery

- Key Figures

- Medicine & Healthcare

- Civil Rights & Black Power

- On #BlackLivesMatter

- Gender & Sexuality

- Diasporic Blackness

- Primary Sources

- Reviews

Economy of Slavery

- “White Women and the Economy of Slavery” by Stephanie Jones-Rogers

White slave-owning women were not the only ones to insist on their profound economic investments in the institution of slavery; the enslaved people they owned and white members of southern communities did too. The testimony of formerly enslaved people and other narrative sources, legal documents, and financial records dramatically reshape current understandings of white women’s economic relationships to slavery, situating those relationships firmly at the center of nineteenth-century America’s most significant and devastating system of economic exchange. These sources reveal that white parents raised their daughters with particular expectations related to owning slaves and taught them how to be effective slave masters. These lessons played a formative role in how white women conceptualized their personal relationships to human property, imagined the powers that they would possess once they became slave owners in their own right, and shaped their techniques of slave control.

STEPHANIE E. JONES-ROGERS

- 15 Minute History Episode 120: Slave-Owning Women in Antebellum U.S. with Dr. Stephanie E. Jones-Rogers

- “Slavery in America: Back in the Headlines” by Daina Ramey Berry

- “Slavery and Freedom in Savannah” by Leslie M. Harris and Daina Ramey Berry

- Visualizing Emancipation(s): Mapping The End of Slavery in America by Henry Wiencek

- An “Act of Justice”? by Juliet Walker

- “Teaching Slavery, Possibilities for Historical Restitution, and the Papers of Indigenous Enslaver Rebecca McIntosh Hawkins Hagerty” by Joanna Batt

If students today actually do learn of the Trail of Tears, very few learn that thousands of enslaved Black people marched alongside their enslavers as they walked the same path from the Southeast to Oklahoma. An awareness of this aspect of history should not in any way diminish our understanding of the acute and traumatic violence unleashed against Indigenous communities, or reduce our focus on the cruelty of white enslavers. Rather, we must understand how tangled the past is, and how slavery’s toxic influence extended into unexpected places.

JOANNA BATT

Slavery & the Family

- 15 Minute History Episode 88: The Search for Family Lost in Slavery with Dr. Heather Andrea Williams

- “Love in the Time of Texas Slavery” by Maria Esther Hammack

I wasn’t looking to find a story of abounding love when researching violent episodes of Texas history. Then I ran across a Texas newspaper article that shed a brief light on the lives of a Black woman and a Mexican man who had lived as husband and wife in the 1840s, twenty-five miles northeast of Victoria, Texas. She was a woman forced to live in bondage in Jackson County, near the town of Texana, in present day Edna, Texas. Her husband was a Mexican man who was likely indentured, employed, or a peon in that same vicinity.

MARIA ESTHER HAMMACK

- Driven Toward Madness: The Fugitive Slave Margaret Garner and Tragedy on the Ohio by Nikki M. Taylor (2016) – reviewed by Signe Peterson Fourmy

- “Let the Enslaved Testify” by Daina Ramey Berry

- “Last Seen: Teaching about Slavery through the Lens of the Domestic Slave Trade and Family Separation” by Signe Peterson Fourmy

The challenge that teachers face is aggravated by a lack of primary sources. The teaching of slavery often centers on documents and accounts created by the enslavers rather than by enslaved people themselves. Plantation records document the productive and reproductive labor enslaved people were forced to perform. Slave auction broadsides, runaway advertisements, wills, deeds, and mortgages attest to their commodification—all from the perspective and through the voices of their enslavers…This erasure from the historical record means that the lives of the enslaved remain largely unknown, and their stories of separation and struggle are untold. So, how can teachers overcome these obstacles?

SIGNE PETERSON FOURMY

Urban Slavery

- 15 Minute History Episode 54: Urban Slavery in the Antebellum United States with Dr. Daina Ramey Berry and Dr. Leslie Harris

- Slavery in Early Austin: The Stringer’s Hotel and Urban Slavery by Clifton Sorrell III

This hotel was one of the many businesses in Austin using enslaved labor, a commonplace practice that extended to every part of Texas. However, urban slavery in Austin differed substantially from slavery on the vast plantations that stretched across Texas’ rural geography. Unlike rural planters, urban slaveholders were largely merchants, businessmen, tradesmen, artisans, and professionals. The urban status of these slaveholders in Austin meant that enslaved people performed a wide variety of tasks, making them highly mobile and multi-occupational. Austin property holders, proprietors, and city planners built enslaved labor not only into the city’s economy, but into its very physical space to meet local needs. This examination of the Stringer’s Hotel provides a brief window for looking into Austin’s history of slavery and perhaps the history of enslaved people in the urban context.

CLIFTON SORRELL III

Key Figures

- “Andrew Cox Marshall: Between Slavery and Freedom in Savannah” by Tania Sammons

- 15 Minute History Episode 105: Slavery and Abolition with Manisha Sinha

- “Rising From the Ashes: The Oklahoma Eagle and its Long Road to Preservation” by Jaden Janak

- “Goddess of Anarchy: Lucy Parsons, American Radical” by Jacqueline Jones

Lucy Parsons’s biography offers several overlapping narratives— a love story between a former slave and a former Confederate soldier, the rise and decline of radical labor agitation, the evolution of race as a political ideology and social signifier, and the trajectory of social reform from Reconstruction through the New Deal. She was a bold, enigmatic woman. Her power to inform and fascinate is enduring and her story, in all its complexity, remains a remarkable one for its useful legacies no less than its cautionary lessons.

JACQUELINE JONES

- “Ordinary Yet Infamous: Hannah Mary Tabbs and the Disembodied Torso” by Kali Nicole Gross

- “Before Red Tails: Black Servicemen in World War I” by Jermaine Thibodeaux

- “Eddie Anderson, the Black Film Star Created by Radio” by Kathryn Fuller-Seeley

- Black Cowboys: An American Story by Ronald Davis

In 1921, while reflecting on the height of the cattle drive era, between 1865 and 1895, then President of the “Old Time Trail Drivers’ Association” of Texas, George W. Saunders, estimated that “fully 35,000 men went up the trail with herds . . . about one-third were negroes and Mexicans.” Eminent historians of African Americans in the West such as Kenneth Porter argue that, “twenty five percent” of all cowboys who participated in cattle drives out of Texas were Black. Yet, this is just the beginning. Some Black cowhands never journeyed to Kansas, driving herds of 2000 to 5000 cattle. Some of these women and men, stayed to work on ranches throughout Texas rather than “go up the trail.” They were cooks, and cowboys, horse breakers and trainers. There was more to being a cowboy than eating dust and crossing swollen rivers.

RONALD DAVIS

Medicine & Healthcare

- “The Odds are Stacked Against Us: Oral Histories of Black Healthcare in the U.S.” By Thomaia Pamplin

Civil Rights & Black Power

- “Black Women in Black Power” by Ashley Farmer

One has to only look at a few headlines to see that many view black women organizers as important figures in combating today’s most pressing problems. Articles urging mainstream America to “support black women” or “trust black women” such as the founders of the Black Lives Matter Movement are popular. Publications, such as Time, laud black women’s political leadership—particularly when they mount a challenge to the status quo such as Stacey Abrams’ victory in the Georgia Democratic Governor primary. At the core of these sentiments is the recognition that black women have developed and sustained a liberal democratic politics that is conscious of and responsive to the interconnected effects of racism, capitalism, and sexism and that their approach can offer insight into current socio-political issues. The media often frames these and other women’s efforts as a manifestation of the current political moment divorced from the longer tradition of black women agitators and organizers to which they belong. Many of the black women making headlines today for their work in advancing civil rights and social justice ideals draw from these earlier traditions, including from the Black Power Movement of the 1960s and 70s.

ASHLEY FARMER

- “Stokely Carmichael: A Life” by Peniel Joseph

- “Muhammad Ali Helped Make Black Power Into a Global Brand” By Peniel Joseph

- 15 Minute History Episode 90: Stokely Carmichael: A Life with Peniel E. Joseph

- US Survey Course: Civil Rights

- Student Showcase – Faubourg Treme: Fighting for Civil Rights in 19th Century New Orleans

- 1863 in 1963 by Laurie Green

- The Sword and The Shield – a conversation with Peniel Joseph

- Beauty Shop Politics by Tiffany Gill

- IHS Panel: “Rodney King and the LA Riots: 30 Years Later”

- “Free Walter Collins!”: Black Draft Resistance and Prisoner Defense Campaigns during the Vietnam War by Sarah Porter

Campaigns around the cases of Black draft resisters like Collins also reveal the particular ways in which civil rights activists engaged in anti-war organizing. Collins’ supporters constructed a large and diverse coalition, and in the process, they developed a critique of the draft as a weapon against movements for social and racial justice. Their campaign blurred the line between foreign policy and domestic politics, revealing how thoughtfully Black civil rights activists situated themselves on the world stage during the 1960s and 70s.

SARAH PORTER

On #BlackLivesMatter

- “#Blacklivesmatter Till They Don’t: Slavery’s Lasting Legacy” by Daina Ramey Berry and Jennifer L. Morgan

In less than a month, our nation will commemorate the 150th anniversary of the 13th Amendment, which abolished slavery. This should be a time of celebratory reflection, yet Wednesday night, after another grand jury failed to see the value of African-American life, protesters took to the streets chanting, “Black lives matter!” As scholars of slavery writing books on the historical value(s) of black life, we are concerned with the long history of how black people are commodified by the state. Although we are saddened by the unprosecuted deaths of Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, Eric Garner and countless others, we are not surprised. We live a nation that has yet to grapple with the history of slavery and its afterlife. In 1669, the Virginia colony enacted legislation that gave white slaveholders the authority to murder their slaves without fear of prosecution. This act, concerning “… the Casual Killing of Slaves,” seems all too familiar today.

DAINA RAMEY BERRY AND JENNIFER L MORGAN

- “Violence Against Black People in America: A ClioVis Timeline” by Haley Price, William Jones, and Alina Scott

- “Stand With Kap”: Athlete Activism at the LBJ Library by Gwendolyn Lockman

Gender & Sexuality

- Slavery, Work, and Sexuality by Daina Ramey Berry

- “Black Women’s History in the US: Past & Present” by Daina Ramey Berry and Kali Nicole Gross

- “Black Women’s Academic Work is Not for the Taking” by Alaina Bookman.

- “We Don’t Have to Boo It:” UT’s Black Lesbian Student Government President by Brynna Boyd

- “Black is Beautiful – And Profitable” by Tiffany Gill

Black is beautiful. The Black Power movement of the 1960s and 1970s popularized this slogan and sentiment, but almost half-a-century earlier, black beauty companies used elaborate advertisements like the one pictured here to sell their vision to uplift and beautify black women. African American women like Madam C.J. Walker produced beauty products and trained women to work as sales agents and beauticians. and in the process, developed an enduring enterprise that promoted economic opportunities and connections with African descendant peoples throughout North and South America.

TIFFANY GILL

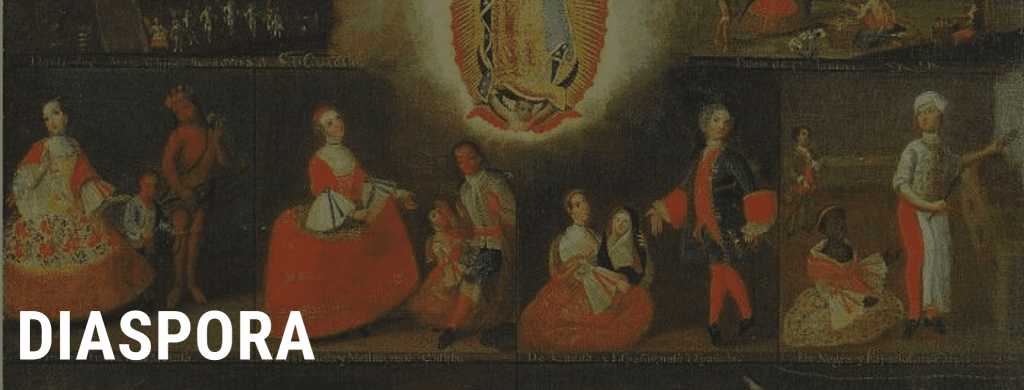

Diaspora

- Slavery and Race in Colonial Latin America

- 15 Minute History Episode 70: Slavery and Abolition in Iran

- Frank A. Guridy on the Transnational Black Diaspora

- African Americans in Ghana: Black Expatriates and the Civil Rights Era by Kevin K. Gaines (2007)

- IHS Podcast: Mexico’s Social Science Laboratory and the Origins of the US Civil Rights Movement (1930-1950)

Primary Sources

Reviews in Black History

- King: Pilgrimage to the Mountaintop by Harvard Sitkoff (2009) by Tiana Wilson

- We Were Eight Years in Power by Ta-Nehisi Coates (2017) By Brandon Render

- Dispossessed Lives: Enslaved Women, Violence, and the Archive by Marisa Fuentes (2016) By Tiana Wilson

Fuentes’ work contributes to the historical knowledge of early America through her focus on violence and how it operated during slavery and continues today through archives. She cautions scholars to avoid traditional readings of archival evidence, which are produced by and for the dominant narratives of slavery. Instead, she calls for a reading “along the bias grain,” of historical records and against the politics of the historiography on a given topic. In other words, she pushes historians to stretch fragmented archival evidence in order to reflect a more nuanced, complex understanding of enslaved people’ lives.

TIANA WILSON

- Monroe by Lisa B. Thompson (2018) by Tiana Wilson

- Historical Perspectives on Marshall (dir: Reginal Hudlin, 2017) by Luritta DuBois

- African Americans in Ghana: Black Expatriates and the Civil Rights Era by Kevin K. Gaines (2007) by Joseph Parrott

- Baseball’s Great Experiment: Jackie Robinson and His Legacy by Jules Tygiel (1997) by Dolph Briscoe IV

- Historical Perspectives on The Birth of a Nation (2016) by Ronald Davis

- A. City Limits: African American Los Angeles from the Great Depression to the Present by Josh Sides (2003) by Cameron McCoy

- Wicked Flesh: Black Women, Intimacy, and Freedom in the Atlantic World by Jessica Marie Johnson (2020) by Tiana Wilson

- The Harder They Fall (2021), Directed by Jeymes Samuel by Candice Lyons

- Vanguard: How Black Women Broke Barriers, Won the Vote, and Insisted on Equality for All by Martha S. Jones (2020) by Tiana Wilson

- Roundtable review of Jeremi Suri’s Civil War by Other Means (2022) by Brandon James Render, Jon Buchleiter, and Sarah Porter

- The Third Reconstruction: America’s Struggle for Racial Justice in the Twenty-First Century by Peniel E. Joseph (2022) by Danielle Sanchez

Joseph draws on his personal experience as a Haitian and a first-generation Black American to understand the Third Reconstruction in the present-day. He also shows what it means to grow up Black in the United States through intertwining stories from his own life with ones that trace Barack Obama’s path to the presidency. Through these stories, he also tracks a shift in American culture, which has contributed to a misleading “post-racial” understanding of American society.

DANIELLE SANCHEZ

- The River of No Return: The Autobiography of a Black Militant and the Life and Death of SNCC 1990), by Cleveland Sellers (with Robert Terrell), reviewed by Kayla Nustad

- Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America (2016), by Ibram X. Kendi, reviewed by Maddie (Williams) Shorman

Ibram X. Kendi’s exploration of the historical roots of racism provided a timely lens through which to understand and address contemporary racial issues during this pivotal period. In addition, it offers an invaluable lens through which contemporary policymakers can confront and dismantle systemic inequities. As a historian and scholar of race and discrimination in America, Kendi takes readers through the annals of American history and reveals the insidious evolution of racist ideologies from their inception to the present day.

MADDIE (WILLIAMS) SHORMAN

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.