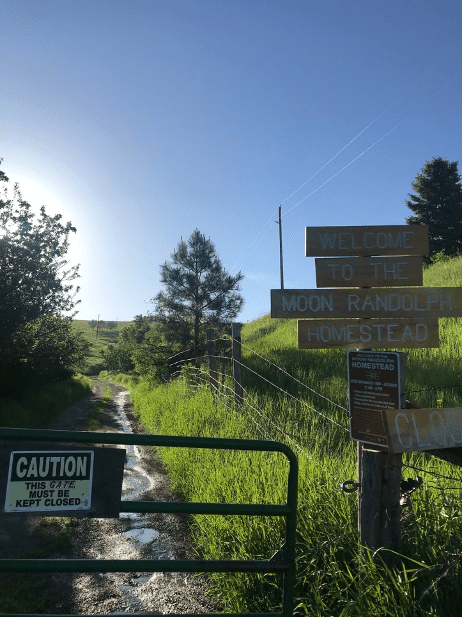

Past the local dump and the interstate, and separated by foothills from the nearby historic neighborhoods of Missoula, Montana, the Moon-Randolph Homestead can be found, steeling itself against the modern world but not quite stuck in the past. It is an unusual historical site where the ecological and the human, and the past and the present melt into one another.

Before U.S. westward expansion and federal homesteading efforts, Indigenous people traversed the North Hills of Missoula on the Trail to the Buffalo. They passed through nearby Hell Gate Canyon, named both for the cold, rough waters of the river and for the ambushes between tribes that occurred at the canyon. Once the U.S. seized the land in the late nineteenth century, homesteaders in the Missoula valley tried to raise subsistence crops and livestock there. These small parcels of land had little of the potential for profit that large, thousand-plus acre ranches enjoyed.

Ray and Luella Moon came to Missoula from Minnesota staking their homestead claim in 1889. They came to “prove up,” sell the land, and move on. Ray Moon sold his land to his relatives, George and Helen Moon, the same day he acquired the deed to the property in 1894. Then Ray and Luella left Missoula. George and Helen Moon had moved to Seattle by 1907. William and Emma Randolph came to Missoula from White Sulphur Springs, Montana to buy a farm so Emma could raise chickens and get William to settle down. The Randolphs tracked down the Moons in Seattle and wrote to them to purchase the land.[1]

William and Emma lived the rest of their lives in Missoula, alternating between the homestead, which they called the Randolph Ranch, and a home in town. They raised their three sons there and often let extended family stay with them for long stretches of time. William and Emma passed away in 1956 within months of each other. Their youngest son, Bill, continued living at ranch until his death in 1995. In 1992, Bill put a conservation easement on his land, which protected it from development after his death. The City of Missoula purchased the nearly 470 acres in 1997 and created the North Hills open space and trail system. Of those acres, 13 became the Moon-Randolph Homestead site. The North Missoula Community Development Corporation, a local nonprofit, created the Hill and Homestead Preservation Commission in 1998 to advocate for the Moon-Randolph Homestead. [2]

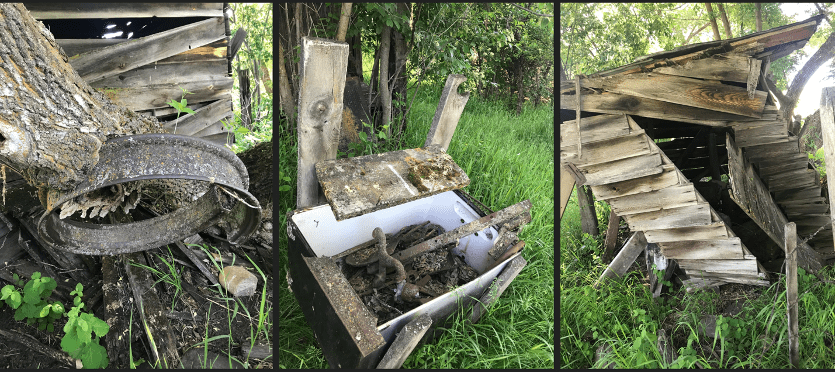

In 1998, the city began a program to house caretakers on site to oversee the Moon-Randolph Homestead, raise livestock, host events, and interface with the public. The Department of Interior listed Moon-Randolph on the National Register of Historic Places in 2010. It is open to the public on Saturdays from 11 am to 5 pm, May through October, and is used by several groups during the week, including the Montana Conservation Corps, Opportunity Resource, Youth Homes, and Parks and Recreation Homestead Camps.[3] Dr. Caitlin DeSilvey, Associate Professor of cultural geography at the University of Exeter, was the first caretaker for the Moon-Randolph Homestead. She wrote her dissertation about her work in the late 1990s and early 2000s cataloging the Randolphs’ belongings.[4] DeSilvey’s scholarship contemplates the role of decay in heritage sites. She advocates for what she calls “encounter[s] with the debris of history,” allowing deterioration to proceed as a mode of historic interpretation.[5] Her approach to Moon-Randolph was to interfere as little as possible with anything on site. Though DeSilvey catalogued all of the artifacts and documents at Moon-Randolph, the decision to curate decay combined with a lack of dedicated city resources left much of what was on site to erode away or be eaten by the mice that inhabit the site.

DeSilvey acknowledged in her dissertation the virtual impossibility that the city-managed property be allowed to totally decay. She suggested that, “Future management of the site will have to find a compromise between a celebration of entropic heritage and the conservation of material traces.”[6] As an intern for the City of Missoula Historic Preservation Office and Department of Parks and Recreation, the priority for my summer job at the Homestead was to help the preservation and interpretations methods for the site to evolve.

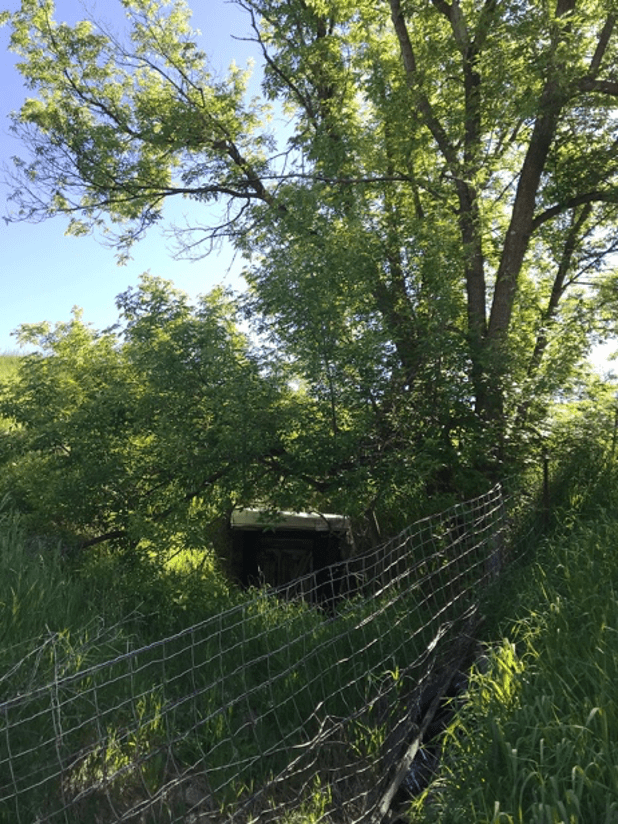

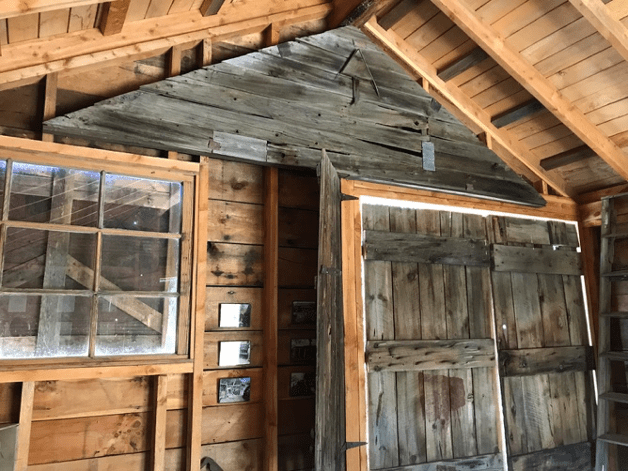

My duties included the curation of the reconstructed Mining Shed. The Mining Shed had been entirely reconstructed, out of both new and salvaged materials, after collapsing in 2014, and exists in direct contradiction with the decay at the Homestead. The original Mining Shed stood from around 1900 until its collapse in 2014. It sheltered a hoist for the small-scale coal mining operation that William Randolph maintained on his land. Coal mining was not an especially profitable venture in Missoula, though at least one company, Hell Gate Coal, successfully mined the North Hills in the early 1900s. The naming of the Coal Mine Road, which led to the family ranches of the North Hills, Randolphs’ included, suggests Missoulians knew the area to bear coal. One must still use Coal Mine Road to get to Moon-Randolph and its neighbors, the city dump included.[7] Coal at the Homestead was likely found by George Moon, if not Ray Moon. Mining was a special interest for William Randolph, who was more of a dreamer and tinkerer than a farmer. The Randolphs’ quaintly named “Little Phoebe” mine produced low-grade coal, mostly traded with neighbors or used at home. They hired men to work in the mine, signaling either some profit or William’s financial dedication to his side projects. Robert, the middle Randolph son, wrote about the mine in his boyhood diary during the winter of 1916-1917. The Randolphs used coal from Little Phoebe until the 1930s, then let it fill with water to use to irrigate the pasture. In 1937, Robert wrote from Spokane, Washington to ask his father if he had given the coal’s use any further thought. William converted the building into a workshop but worked around the hoist, which still stands in its original place. Snow in the winter of 2014 caused the original building’s collapse. City and private crews completed the reconstruction in 2018. The new building is slightly larger than the original structure but is a close reproduction of the old shed.[8]

My curation of the Mining Shed sought to more formally interpret the space while maintaining the Homestead as a place both lost to time and still writing its history. The floor space must be kept free so that the building can be used as a gathering space in inclement weather. It is the safest and largest covered space on site, which will be slow to change, because historic site classification restrictions prohibit new permanent foundation construction. The Mining Shed interpretation does not recreate a specific year of its lifespan but instead illustrates the several layers of its use over time and restoration. We arranged artifacts from mining and shop work. We integrated elements of the original building into the structure of the new building. This protects the intact remains of the old shed and makes the reconstruction apparent through comparison. I wrote limited interpretative signage and selected for display original documents from the Moon Cabin archive related to William Randolph’s mining ventures away from the Homestead.

One of my goals for the Mining Shed was to connect the Homestead to Montana’s economic history from statehood in 1889 through the post-war era. The Moon-Randolph history connects Missoula’s river, trade, agriculture, timber, mining, and railroad economy and history. William Randolph’s investments and work in Montana and beyond call attention to the several ways he sought to make money outside of agriculture. His ventures included work for Standard Brick Company in Missoula, management of the Sibley timber property in Lolo, Montana, and attempts at placer mining in the Nine Mile Valley east of Missoula. Presenting this history highlights piecemeal economic survival in Montana prior to the 1960s and the survival of the Randolphs’ story through material and documentary evidence.

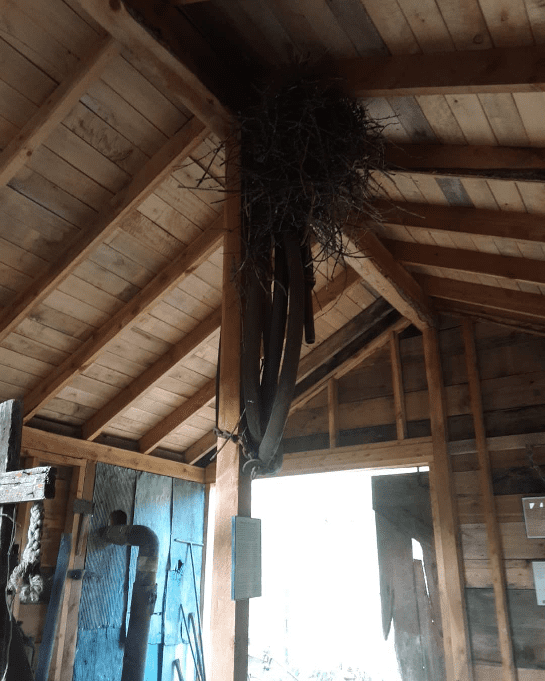

These changes marked a shift toward formal curation at Moon-Randolph. However, we sought to maintain “The Spirit of the Homestead,” a term defined in the Moon-Randolph Strategic Plan Update for 2015-2024. The Spirit of the Homestead aims to maintain Moon-Randolph as “a living place, where historic activities continue and new uses are established, and a place where natural processes of aging and ecological renewal can be appreciated.”[9] The idea of “living history” at the site is not produced as reenactment or period restoration. Rather, the Homestead is kept “alive.” Trees overtake metal refuse from rusty, repurposed farm equipment. There are mice, chipmunks, rabbits, songbirds, hawks, snakes, deer, and the occasional bear. Buildings collapse. Caretakers raise pigs and chickens, haul non-potable water for irrigation from a cistern, and tend to a 130-year-old orchard that still produces cider apples. There is almost no signage and very little written interpretation. The site is left to speak for itself, otherwise visitors must speak to a caretaker or volunteer to ask questions, enjoy a tour, or help with chores.

And speak for itself it does: when I returned to the Homestead in May 2020 for a socially distanced excursion, the mining shed had new tenants. Magpies built their winter nests in the rafters of the reconstructed shed. Springtime bunnies darted in and out of the shed. Their curation enhanced ours. As much as there is curated decay at the site, there, too, is resplendent life. History and the present, decay, life, and curation, negotiate their coexistence in the North Hills of Missoula.

[1] DeSilvey, Butterflies and Railroad Ties; DeSilvey, Salvage Rites; Moon-Randolph Homestead, “History,” https://www.moonrandolphhomestead.org/history; Montana Association of Land Trusts, “About Conservation Easements,” http://www.montanalandtrusts.org/conservationeasements/; North Missoula Community Development Corporation, “Moon Randolph Homestead,” http://www.nmcdc.org/programs/moon-randolph-homestead/; United States Department of the Interior, National Parks Service, National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet, Moon-Randolph Ranch, March 1, 2010, https://www.nps.gov/nr/feature/presmonth/2010/Moon-RandolphRanch.pdf; “Moon-Randolph Strategic Plan Update: 2015-2024,” 2-5.

[2] Caitlin DeSilvey, Butterflies and Railroad Ties: a History of a Montana Homestead, second edition (Missoula, MT: Hill and Homestead Preservation Commission, 2002); Caitlin DeSilvey, Salvage Rites: Making Memory on a Montana Homestead, doctoral dissertation, Open University (2003); Moon-Randolph Homestead, “History,” https://www.moonrandolphhomestead.org/history; City of Missoula, North Missoula Community Development Corporation, and Five Valleys Land Trust, “Moon-Randolph Strategic Plan Update: 2015-2024,” Final, Adopted by Missoula City Council May 4, 2015, 7, https://www.ci.missoula.mt.us/DocumentCenter/View/31846/MoonRandolphHomestead_StrategicPlan_2015?bidId=.

[3] Moon-Randolph Homestead, “History,” https://www.moonrandolphhomestead.org/history; North Missoula Community Development Corporation, “Moon Randolph Homestead,” http://www.nmcdc.org/programs/moon-randolph-homestead/; United States Department of the Interior, National Parks Service, National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet, Moon-Randolph Ranch, March 1, 2010, https://www.nps.gov/nr/feature/presmonth/2010/Moon-RandolphRanch.pdf; Moon-Randolph Homestead, “Welcome,” https://www.moonrandolphhomestead.org/.

[4] University of Exeter, “Professor Caitlin DeSilvey,” College of Life and Environmental Sciences, Geography Department, http://geography.exeter.ac.uk/staff/index.php?web_id=Caitlin_Desilvey; DeSilvey, Salvage Rites; “Moon-Randolph Strategic Plan Update: 2015-2024,” 4-5.

[5] DeSilvey, Salvage Rites, 10.

[6] DeSilvey, Salvage Rites, 176.

[7] City of Missoula, Historic Preservation Office, Moon-Randolph Homestead Records; DeSilvey, Butterflies and Railroad Ties; DeSilvey, Salvage Rites; National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet, Moon-Randolph Ranch, March 1, 2010; J.T. Pardee, “Coal in the Tertiary Lake Beds of Southwestern Montana,” Contributions to Economic Geology, Part II (1911);

[8] DeSilvey, Butterflies and Railroad Ties; DeSilvey, Salvage Rites; National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet, Moon-Randolph Ranch, March 1, 2010; Robert Randolph, Diary, 1916-1917, Moon-Randolph Archive; City of Missoula, Historic Preservation Office, Moon-Randolph Homestead Records.

[9] “Moon-Randolph Strategic Plan Update: 2015-2024,” 7.

You might also like: