Guest: Linda Gordon, Professor Emerita of History at New York University

Host: Alina Scott, PhD Candidate in the History Department at the University of Texas at Austin

Historians argue that several versions of the group known as the Ku Klux Klan or KKK have existed since its inception after the Civil War. But, what makes the Klan of the 1920s different from the others? Linda Gordon, the winner of two Bancroft Prizes and the Los Angeles Times Book Prize, writes in The Second Coming of the KKK The Ku Klux Klan: of the 1920s and the American Political Tradition that the KKK of the 1920s expanded its mission to include anti-Black racism, anti-Catholicism, and anti-Semitism, electing legislators and representatives in government, and were hyper-visible. “By legitimizing and intensifying bigotry, and insisting that only white Protestants could be ‘true Americans,’ a revived and mainstream Klan in the 1920s left a troubling legacy that demands a reexamination today.” With more than a million members at its peak, the Second coming of the KKK was expansive, to say the least.

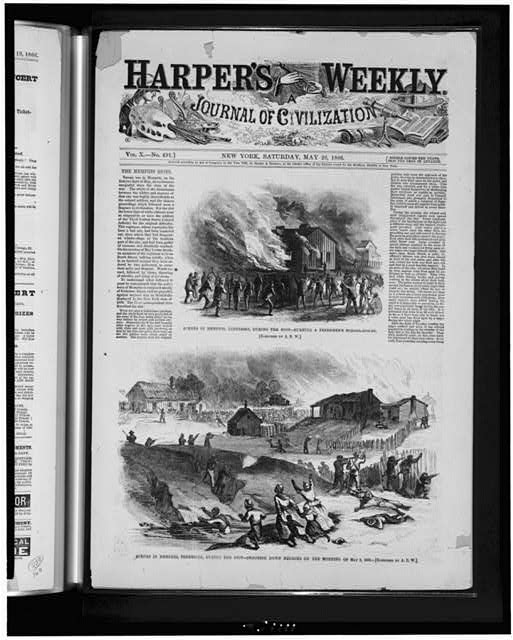

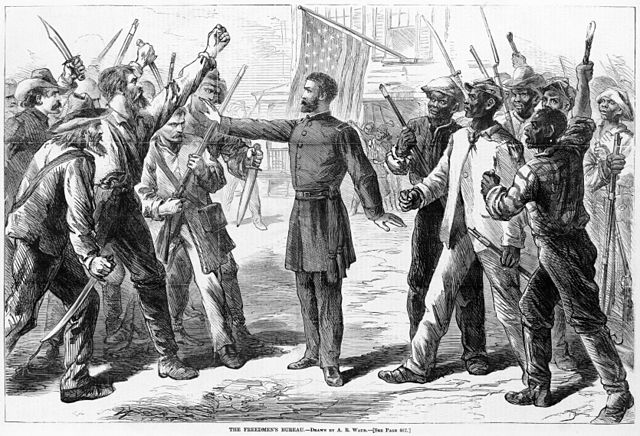

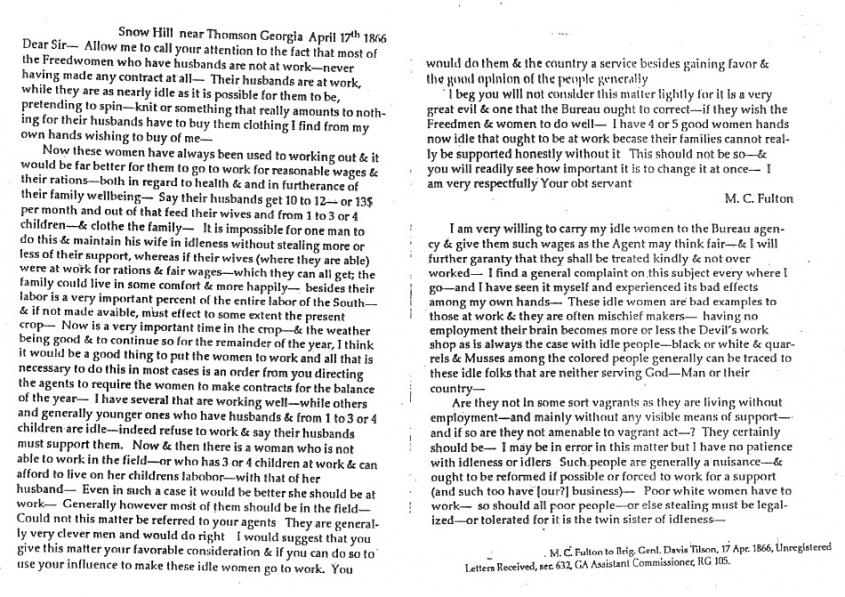

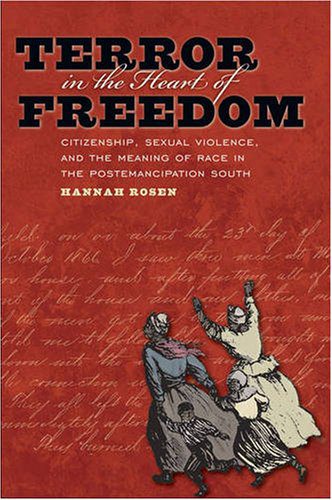

Hundreds of thousands died or were wounded in combat, entire cities were destroyed, and afterwards, the large segment of the nation that had seceded had to be reincorporated into the national body, and a new citizen-subject remained to be embraced by post-bellum societies. Hannah Rosen’s Terror in the Heart of Freedom analyzes the experiences of recently freed blacks, released from the bonds of slavery and plantation life, who sought to create new lives as freedmen and women. Many headed to cities as part of a “mass exodus from slavery.” The city of Memphis, Tennessee became one such “city of refuge” where freedpersons practiced their freshly conferred citizenship. They established new communities, built churches, opened their own schools, and formed African American benevolence societies that sponsored community events. In short, freedpersons in Reconstruction Memphis, as in many other cities, catalyzed changes in the socio-spatial boundaries of urban spaces that had previously been closed to them.

Hundreds of thousands died or were wounded in combat, entire cities were destroyed, and afterwards, the large segment of the nation that had seceded had to be reincorporated into the national body, and a new citizen-subject remained to be embraced by post-bellum societies. Hannah Rosen’s Terror in the Heart of Freedom analyzes the experiences of recently freed blacks, released from the bonds of slavery and plantation life, who sought to create new lives as freedmen and women. Many headed to cities as part of a “mass exodus from slavery.” The city of Memphis, Tennessee became one such “city of refuge” where freedpersons practiced their freshly conferred citizenship. They established new communities, built churches, opened their own schools, and formed African American benevolence societies that sponsored community events. In short, freedpersons in Reconstruction Memphis, as in many other cities, catalyzed changes in the socio-spatial boundaries of urban spaces that had previously been closed to them.