This episode of IHS podcasts highlights the work of Dr. James Sidbury, Andrew W. Mellon Distinguished Professor of Humanities and Professor of History at Rice University where he is also a faculty member of the Center for African and African American Studies . The episode also features Dr. Cañizares-Esguerra, the Director of the IHS, and Ashley Garcia, a PhD Candidate in History at UT Austin.

Introduction

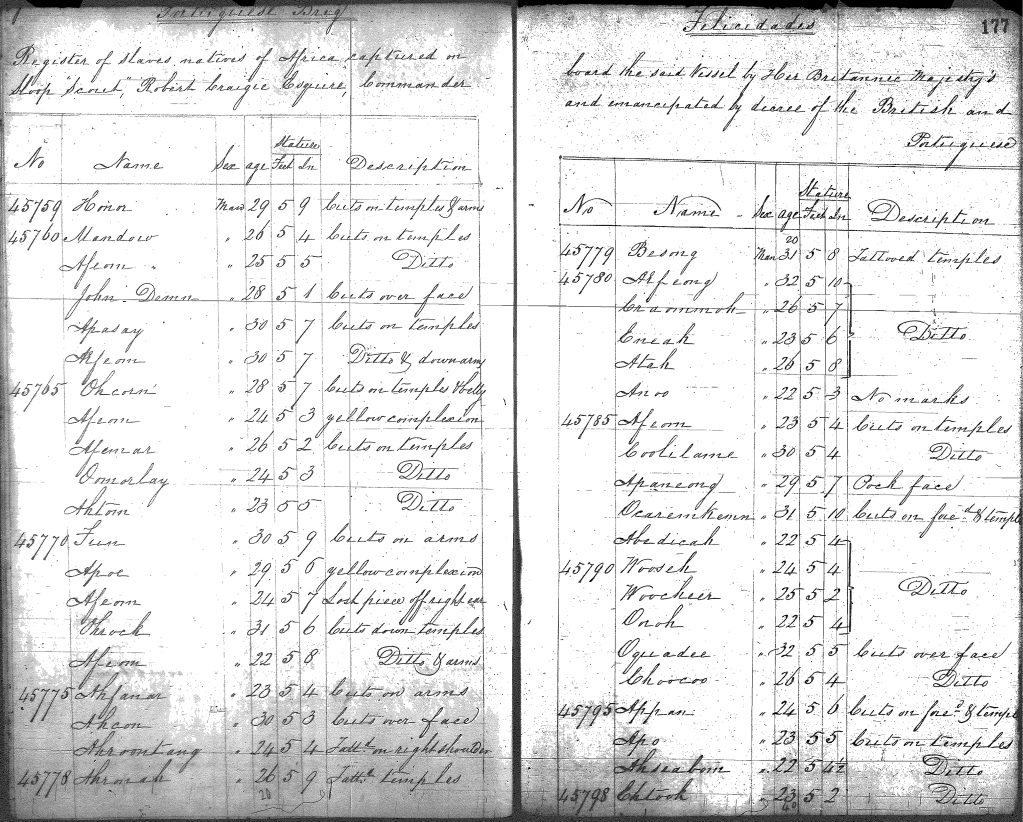

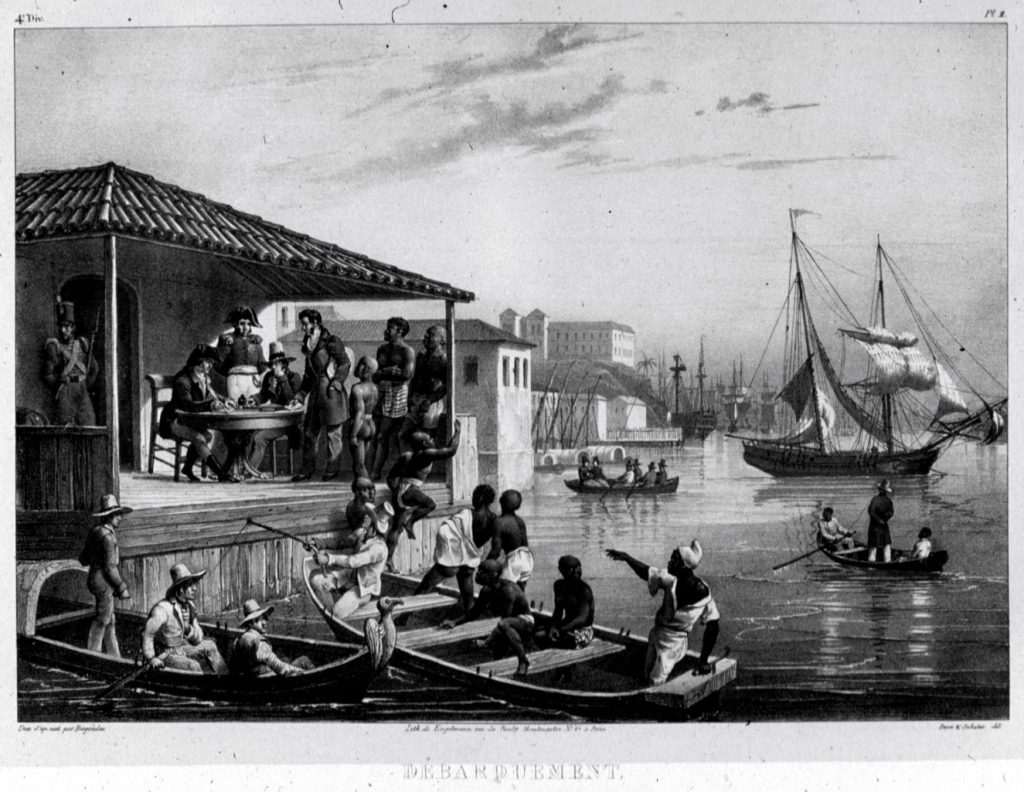

In his forthcoming book E Pluribus Tria: Colonial Racial Formation in the Making of American Culture, James Sidbury explores the origin in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century continental British America of corporate boundaries among European settlers, Native Americans, and Black people, along racial color lines.

How did the Linnaean classification of humans around alleged skin “color” (white, red, and black) become a lived reality for these three communities by the late eighteenth century? Both Black and Native people became foreigners (slaves or savages) in a new republic that only extended the franchise to white people as citizens. Black people responded by developing religious and political collective identities of new Israelites, an elected people awaiting delivery in a new promised land of freedom, Africa. Native American peoples also managed to overcome fragmented ethnic identities to become one new people, “Indians.” Pontiac and Tecumseh led Native Americans into broad pan-ethnic military alliances. Yet “Indians” never fully developed a corporate racial identity, for Native Americans kept incorporating ethnic outsiders as kin by raiding captives. In this podcast, Sidbury traces the slow emergence of broad corporate identities around race in British continental America.

Sidbury argues that race was not just the product of European ideologies of whiteness: Top down taxonomies imagined by naturalists and settlers. Race was a slow process of corporate boundary creation through epidemics, deep demographic transformation, warfare, land dispossession, and plantation violence.

~ Jorge Cañizares-Esguerra

Guest

Dr. James Sidbury is the Andrew W. Mellon Distinguished Professor of Humanities and Professor of History at Rice University where he is also a faculty member of the Center for African and African American Studies. He received his PhD from Johns Hopkins University in 1991 and taught at the University of Texas at Austin from 1991 until 2011. He is a historian of race and slavery in the English-speaking Atlantic world from the seventeenth to the nineteenth century with a special interest in the ways that non-elite peoples conceived of their histories and, through their histories, their collective identities. He teaches graduate and undergraduate courses on Atlantic History, Early North American History, and the history of race and slavery in the United States and the Caribbean.

Hosts

Jorge Cañizares-Esguerra is Alice Drysdale Sheffield Professor of History at the University of Texas at Austin and the Director of the Institute for Historical Studies.

Ashley Garcia is a PhD candidate at the University of Texas at Austin. Her research includes 19th century political history, American communitarianism, and American political thought. Her dissertation, “An American Socialism: The Associationist Movement and Nineteenth Century Political Culture,” explores America’s most popular utopian socialist program: the Associationist movement of the 19th-century. Ashley has also completed a Portfolio in Museum Studies as her secondary PhD field.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.