In honor of the centennial of the Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection, the 2022 Lozano Long Conference focuses on archives with Latin American perspectives in order to better visualize the ethical and political implications of archival practices globally. The conference was held in February 2022 and the videos of all the presentation will be available soon. Thinking archivally in a time of COVID-19 has also given us an unexpected opportunity to re-imagine the international academic conference. This Not Even Past publication joins those by other graduate students at the University of Texas at Austin. The series as a whole is designed to engage with the work of individual speakers as well as to present valuable resources that will supplement the conference’s recorded presentations. This new conference model, which will make online resources freely and permanently available, seeks to reach audiences beyond conference attendees in the hopes of decolonizing and democratizing access to the production of knowledge. The conference recordings and connected articles can be found here.

En el marco del homenaje al centenario de la Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection, la Conferencia Lozano Long 2022 propició un espacio de reflexión sobre archivos latinoamericanos desde un pensamiento latinoamericano con el propósito de entender y conocer las contribuciones de la región a las prácticas archivísticas globales, así como las responsabilidades éticas y políticas que esto implica. Pensar en términos de archivística en tiempos de COVID-19 también nos brindó la imprevista oportunidad de re-imaginar la forma en la que se llevan a cabo conferencias académicas internacionales. Como parte de esta propuesta, esta publicación de Not Even Past se junta a las otras de la serie escritas por estudiantes de posgrado en la Universidad de Texas en Austin. En ellas los estudiantes resaltan el trabajo de las y los panelistas invitados a la conferencia con el objetivo de socializar el material y así descolonizar y democratizar el acceso a la producción de conocimiento. La conferencia tuvo lugar en febrero de 2022 pero todas las presentaciones, así como las grabaciones de los paneles están archivados en YouTube de forma permanente y pronto estarán disponibles las traducciones al inglés y español respectivamente. Las grabaciones de la conferencia y los artículos relacionados se pueden encontrar aquí.

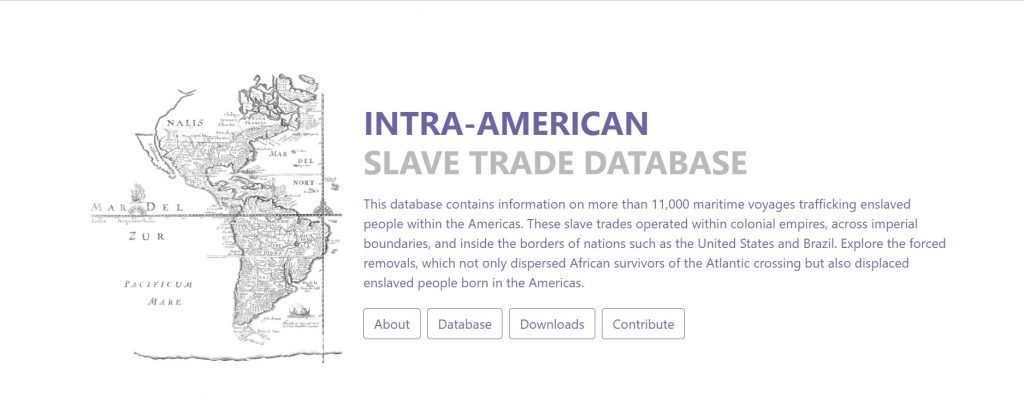

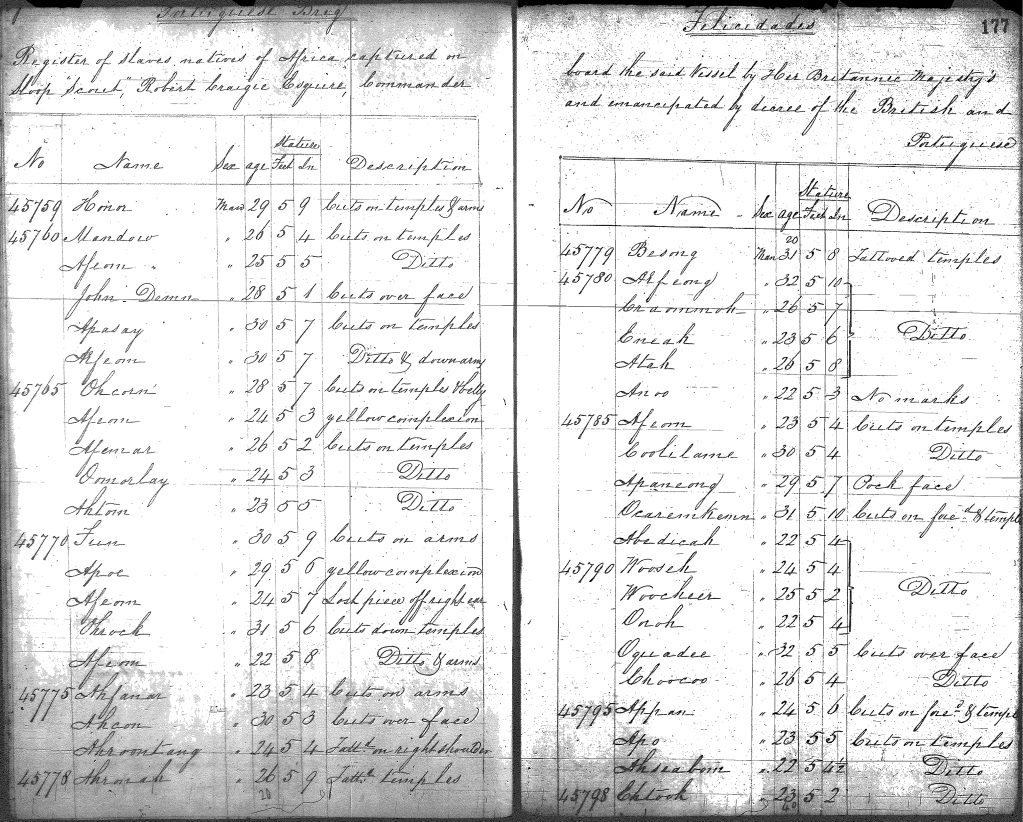

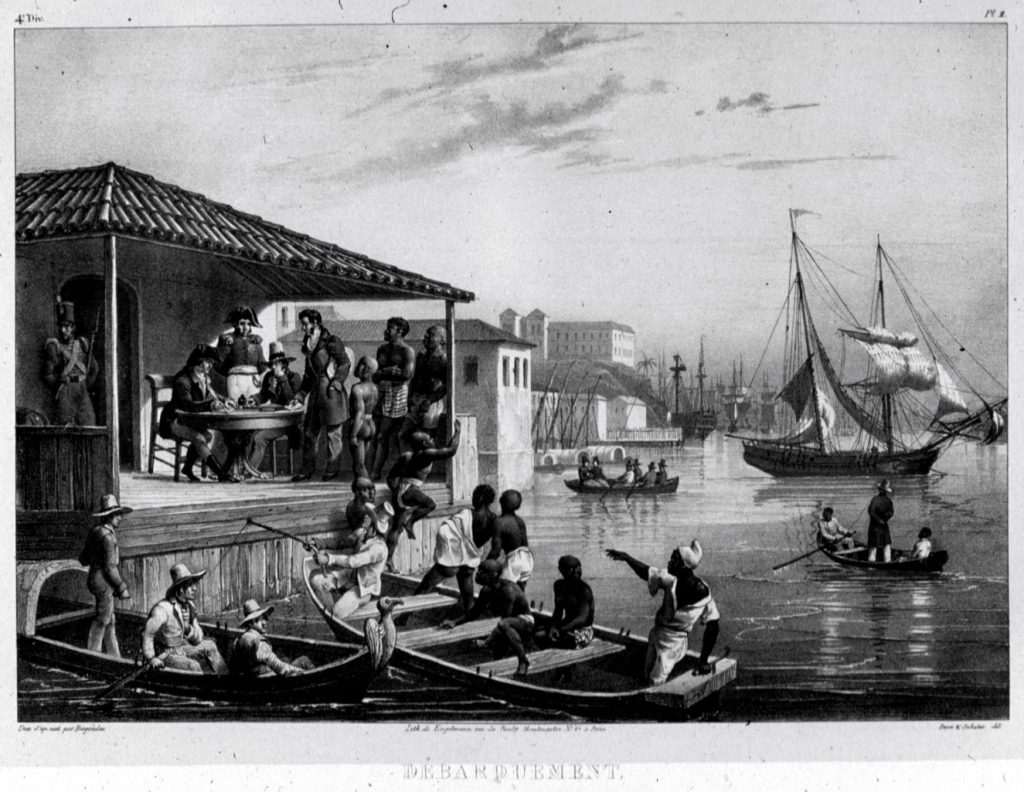

In 2018, Gregory O’Malley and Alex Borucki published the Intra-American Slave Trade database to the Slave Voyages project, which now records more than 27,000 slave voyages across the Americas.[1] After enslaved people disembarked from their forced Trans-Atlantic journeys, many more were re-shipped and dispersed across the Americas to French, Dutch, English, Spanish, and Portuguese outposts and ports. Each unit in the database is composed of a single vessel’s voyage between its place of embarkation and disembarkation of captives. Sources such as port logs, merchant papers, and the logs of import duties record the arrival and departure of slaving vessels. The database includes records on voyages dating from the mid-sixteenth century to the later end of the mid-nineteenth century.

In line with the theme of the 2022 Lozano Long Conference, “Archiving Objects of Knowledge with Latin American Perspectives,” O’Malley and Borucki’s project sheds light on the significance of Latin America in the broader interconnected development of Atlantic Slavery throughout the Americas. Those visiting the database will find that the bulk of the intra-American slave trade was directed predominately towards the Spanish American mainland and Caribbean colonies. Indeed, the mainland Spanish colonies alone received 38% of the total volume of the Intra-American slave trade that crossed colonial boundaries.[2]

Notable re-export colonies included Portuguese Brazil and British Jamaica, where local merchants transshipped many thousands of enslaved people to other colonies. Such data illuminates the importance of what scholars have referred to as the entangled and integrated nature of the broader Atlantic world. Moreover, the data presented by the database illustrates the centrality of Latin America in broader conversations about the Atlantic concerning archives, slavery, and the African diaspora.

In my interview with O’Malley and Borucki, I asked a series of questions, encouraging them to reflect on some of the project’s significant challenges, insights, and contributions. In what follows is a brief introduction to their work through an abridged recap of our engaging conversation.[3] Borucki’s initial research examined enslaved people working on cattle ranches along the borders between Uruguay and Brazil. While working on his dissertation under the supervision of David Eltis, who was then compiling the first online iteration of the TAST (Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade) database, Borucki came across extensive documentation of trans-imperial slave trafficking leading to the colonies in the Rio de la Plata and Venezuela. Since that time, his focus has been on slave trafficking and the routes enslaved people took, shaping their experiences and identities in Latin America (particularly Montevideo and Buenos Aires). O’Malley’s interest in the intra-American slave trade was also sparked after encountering a profuse body of records documenting inter-imperial slave trafficking between different British imperial colonies.

Among the many challenges O’Malley and Borucki faced compiling the database, perhaps the most significant was accounting for the issue of the intra-American contraband slave trade. While scholars have widely acknowledged evidence of the commonplace and ubiquity of illicit slave trafficking, accounting for the phenomena in the database posed a methodological challenge. The difficulties in acquiring and assessing records of clandestine slave trafficking challenge the ability to quantitatively account for it since a single slave voyage constitutes a unit in the database. Furthermore, Borucki notes that in many instances, the records that account for enslaved people as contraband lack sufficient details and information necessary for the identification of a slave voyage.

For example, he explains that in Venezuela, the records for the enslaved people who entered as contraband, as documented in individual records, show that they become legalized property through a regulated process called indulto. However, these sources lack information to connect these individuals to a specific slave voyage. Like the issue of accounting for the illicit slave trade, O’Malley notes the lack of data on the intra-American slave trade to the French Caribbean, which he and Borucki recognize as being vastly underrepresented in the database. Throughout much of the colonial period, the French colonies were on the receiving end of this contraband trafficking however, as Borucki observed, the French seldom produced records detailing these networks from their vantage point.

Nevertheless, in tracing the trafficking of enslaved people across imperial boundaries, O’Malley stated that “building the database forced me to reckon with how entangled empires were.” “I thought when I was starting out that I was mostly working on a project of movements of people within the British Empire and especially from the Caribbean to the North American colonies,” he explains. “But during the quantitative work of tracking all of these movements, I came across all of these voyages going out from Jamaica and other places, to Spanish colonies and French colonies.”

In Borucki’s research on Black social organizations and Catholic confraternities in Montevideo and Buenos Aires, he found that many enslaved people were not African-born but were born and trafficked from Brazil. Such communities had forged networks and connections between the Rio de la Plata and Brazil, further illustrating the importance of intra-American slave trading. Likewise, Borucki explains that this project raises questions about the trafficking of slaves and the trans-imperial formation of Black communities––their movement, experiences, and ideas that flow between imperial borders. Together these complicate our idea of trans-imperial connections.

For O’Malley, “the thing that’s most striking with the intra-American database, specifically, is the sense of the scope of slavery in the Americas.” Indeed, while the Trans-Atlantic slave trade gives you the immense scale of transatlantic trafficking, “those voyages tend to go to a relatively small number of ports over and over again.” However, the Intra-American database draws our attention to those far-flung outposts, colonial backwaters, and ports, that when viewed together with the TAST data, truly illustrate the ubiquity of slavery across the Americas. In particular, Borucki points out that there was “a very active traffic in slaves in the Pacific “from Panama going down to a Lima, Peru, also across South America, from Buenos Aires going down to the Magellan straits and then north into Lima, and also from Central America going north as well.”

It is his hope that future historians will be able to capture this data, “to have some kind of representation really––– each little archive in Oaxaca, in Michoacán, in the western parts of Mexico have records on enslaved people of African ancestry being moved around to the confines of the Americas.” As new research continues to come to the fore adding new perspectives to the way we understand the broader history of the African diaspora and slavery across the Americas, the intra-American database will continue to be of importance to a wide variety of educators and scholar.

Borucki is a contributor to the upcoming 2022 Lozano Long Conference, honoring the centennial of the Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection, entitled “Archiving Objects of Knowledge with Latin American Perspectives.” Readers interested in learning more about their work are encouraged and invited to attend their panel at the conference entitled “Public, Access, and the Archival Dimensions of Digital Humanities.” For more information, stay tuned for updates at PORTAL, the Llilas Benson Latin American Studies and Collections official online magazine.

Clifton E. Sorrell III is a third year History PhD student at the University of Austin at Texas. He earned a B.A in both African American Studies and History at the University of California, Davis, and is currently studying Atlantic Slavery and the African Diaspora under Professor Daina Ramey Berry. He is broadly interested in the politics of African Diaspora Freedom practice in the Anglophone-Spanish Caribbean in between the 17th and 18th century. His research covers a broad set of questions concerning African diasporic resistance in the inter-imperial geo-politics of the circum-Caribbean, gender, diasporic cultural politics and social recreation.

[1] “Intra-American Slave Trade,” Slave Voyages. Accessed November 10th, 2021. https://www.slavevoyages.org/american/about#methodology/0/introduction/0/en/

[2] Ibid

[3] I would like to thank Gregory O’Malley and Alex Borucki for taking the time to meet with me to conduct this interview. Clifton Sorrell in Conversation with (Authors) Gregory O’Malley and Alex Borucki (Conducted Nov. 9, 2021).

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.