By Josh Urich

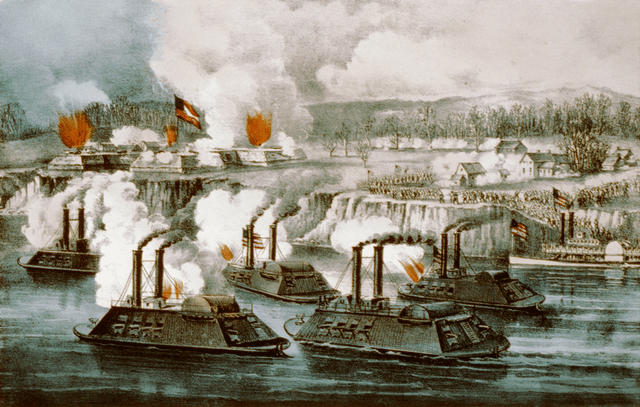

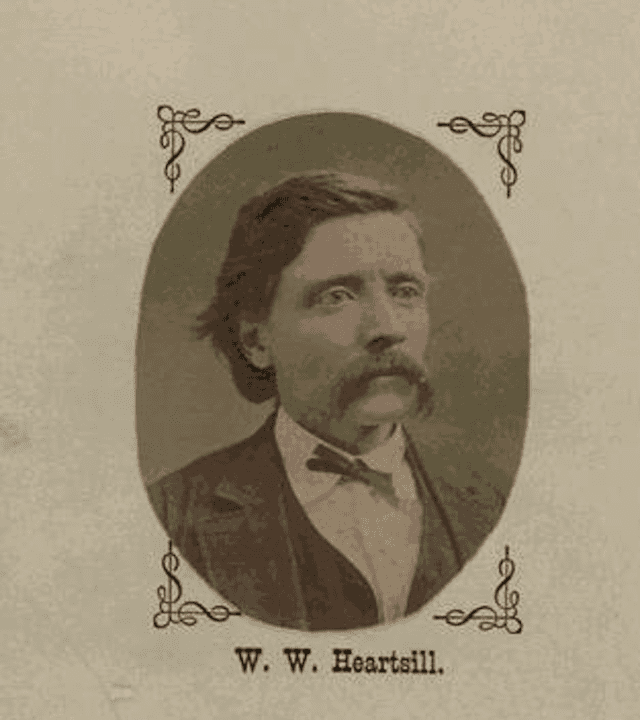

William Williston Heartsill volunteered to fight for the South before the Civil War even began. For the first two years of his service, he and his comrades from Harrison County, Texas served as a cavalryman on Texas’s western frontier. His unit, the W.P. Lane Rangers, finally saw combat at the Battle of Arkansas Post on January 11, 1863. They were captured on the second day of combat. Heartsill spent several months in Camp Douglas in Illinois and then was exchanged for Union prisoners.

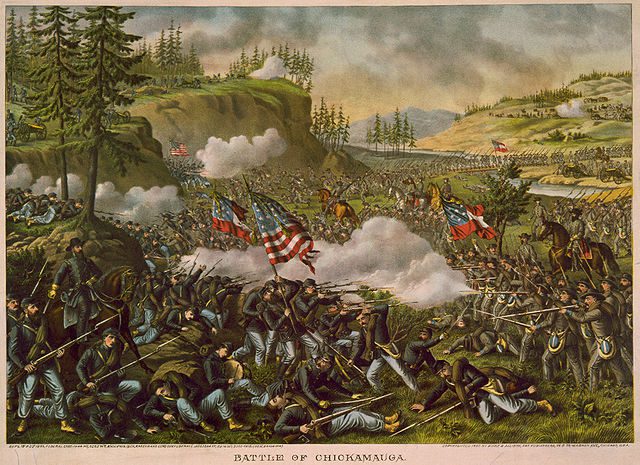

Upon their release, the Lane Rangers were separated and Heartsill was mustered into General Braxton Bragg’s infantry. Heartsill resented serving as a conscripted infantryman and longed to rejoin the rest of his volunteer unit on horseback. After the battle Chickamauga, and mere days before the battle of Chattanooga, Heartsill and one of his fellow Rangers abandoned Bragg’s army and headed back to Texas to rejoin the W.P. Lane Rangers. They succeeded after a month of dangerous travel.

The Lane Rangers saw little combat before they were dissolved in mid-1865. Five years after the war concluded, Heartsill printed one thousand copies of his wartime diary––although not before editing it to defend his desertion and his company’s honor. Shortly after his diary was published, he was elected mayor of Marshall, Texas, Harrison’s county seat. In the ensuing decades, Heartsill was active in the leadership of the Marshall camp of the United Confederate Veterans and was involved in both regional politics and business.

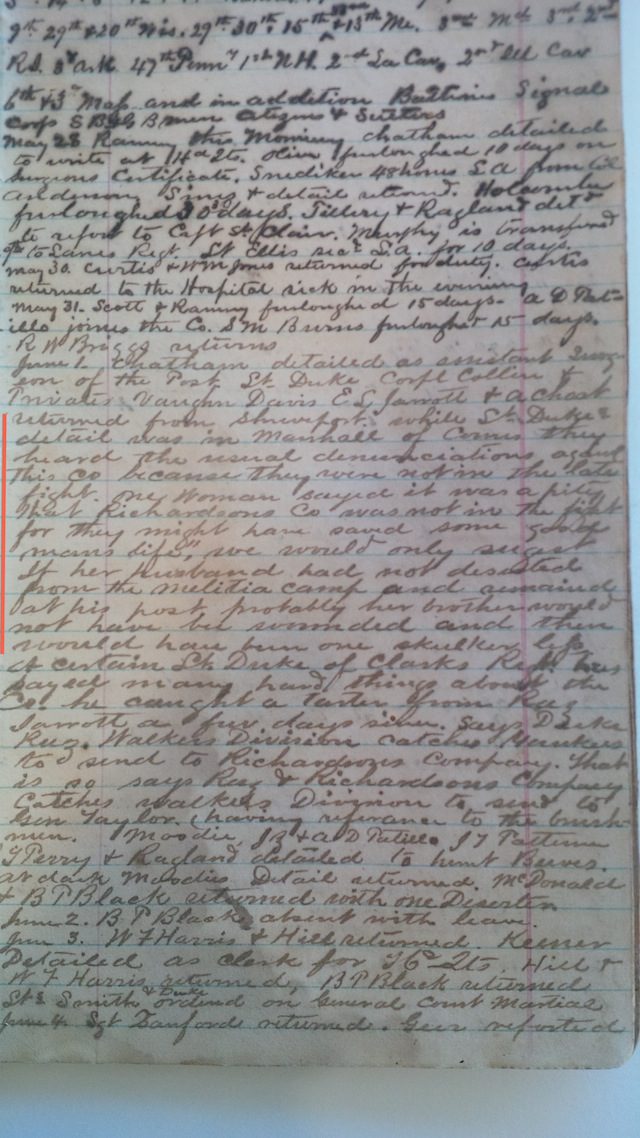

The section of the diary below is taken from the June 1, 1864 entry of Heartsill’s diary. At this point in the war, Heartsill had already abandoned Bragg’s army and rejoined the Rangers in the same place they started, Harrison County, Texas. After a number of weeks back in Harrison, Heartsill and the men began to hear “denouncements” against them. There were several reasons the townspeople turned against the Rangers. During their service, they had lost about ten percent of their company. By contrast, other units from Harrison County lost an average of fifty percent each. Many people in the county lost children or siblings from these other units. It was natural for townspeople who had lost loved ones to feel resentful towards the Rangers, considering their high survival rate. The Rangers were also an independent company and their limited combat experience, especially compared to the county’s other units, would have reflected poorly on their honor, an important southern value.

Finally, the townspeople provided both emotional and material support to the Texan units. The townspeople must have wondered why the W.P. Lane Rangers accepted all of the town’s support but were not out on the frontlines. For the woman mentioned in this entry in particular, though, the root of her frustration was clearly the death of her relative. How must she have felt, seeing the Rangers still in Marshall––the Rangers who rarely saw combat, and who never, even at Arkansas Post, experienced casualty rates as high as most companies?

This document points to the internal conflicts that ate at the Confederacy from the local level up. Not only was Heartsill himself a deserter (at least briefly), but so also was this woman’s husband––if Heartsill is to be believed. Moreover, the financial burdens that companies placed upon towns put stress on loyalty to the southern cause.

William Williston Heartsill’s papers are held at the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, University of Texas at Austin.

You may also like in Texas History:

Confederados: The Texans of Brazil

“The Battle of Bandera Pass and the Making of Lone Star Legend”

A Texas Ranger and the Letter of the Law

“The Die is Cast”: Early Texans Face the Comanches

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.