From the editors: The Digest: Food in History is a new series from Not Even Past that focuses on the exciting field of food history . Across these pieces, contributors will explore the intimate intersections between food, people, ecologies, and history. The Digest: Food in History will publish a range of research connected to food production, distribution, and consumption and use this to reflect on wider historical questions.

In the first installment of The Digest, Atar David, a Ph.D. candidate in the University of Texas at Austin’s Department of History and the Associate Editor for Not Even Past, reflects on some lesser known and more controversial aspects involved in the creation Southern California’s date production monopoly. The article invites readers to rethink their food conventions and question the relationship between food and power.

Southern California produces almost half of the date fruits consumed in the US today. But that was not always the case. Date fruits became popular among American consumers during the last quarter of the nineteenth century, but since no one in the US grew dates for commercial purposes, supply depended on imports from the Middle East, especially from the Arab Gulf. The first attempts to cultivate dates on a commercial scale in Arizona and California began at the turn of the twentieth century. However, America still ran on imported dates until the 1920s, when the region around the Salton Sea became the leading date-producing center in the country. By the 1930s, California production was robust enough to reduce the need for imports and provide most local consumption.

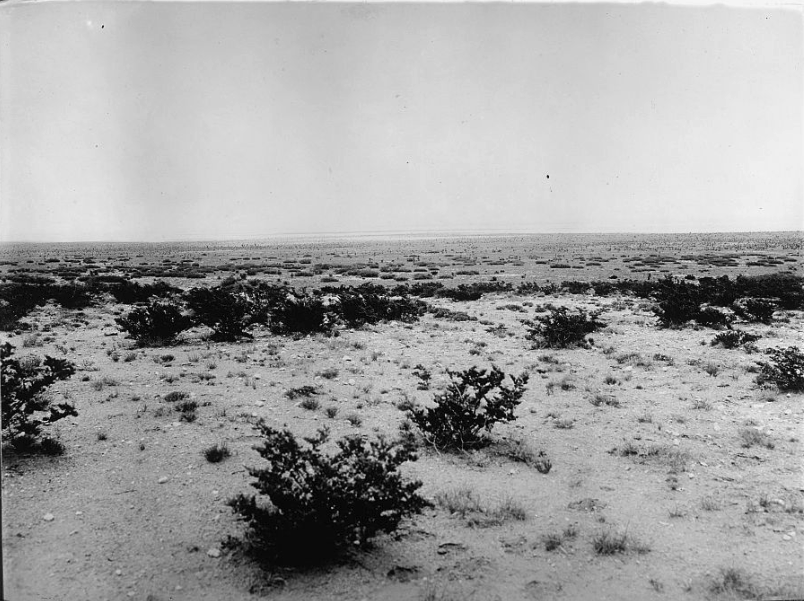

How did Southern California become the leading date-producing region in the country? One possible explanation has to do with the local climates. The region’s long and dry summers are notoriously harsh and, for years, posed a challenge to settlers. But these climatic predicaments are advantageous for date palms (Phoenix Dactylifera L.), whose fruits can only ripen during extensive heat. Common narratives of California’s date sector often stress how federal officials import date palm offshoots (more on that to come) from the Middle East and perfected cultivation, packing, and distribution methods until they finally achieved victory over nature’s setbacks. According to this narrative, perseverance and ingenuity made California a date production center.

My research, which examines the global circulation of date palm commodities from the late nineteenth to the mid-twentieth century, paints a more complex version of this story. As a part of my work, I got to know the federal agents involved in establishing the California date cultivation sector. Since they operated during the Progressive Era and were motivated by visions of improvement, I call them Date Boosters.

After reading correspondents, their memories, and their official reports, I realized that scientific curiosity and dreams of greening the desert were not date boosters’ only motivation. Instead, they were driven by a desire to establish and then maintain their monopoly over date cultivation. To do so, they sometimes lied, deceived, and ostracized other growers and fellow federal agents. As it turns out, their at-times shady actions were as meaningful to California’s ascendent to a national (and later global) date production center as the local climates. Examining some of the shadier aspects of their operation reveals the messy politics behind California’s successful date cultivation operation and the often-unspoken realities of the politics of food production.

Offshoot Monopoly

Date boosters had already started dreaming about an all-American date sector by the early 1890s. At that time, no one cultivated dates for commercial purposes in the US, and the only date palms around were the offspring of palms brought to the country by Spanish missionaries during the seventeenth century. Boosters imported seeds from Mexico and various places around the Middle East and planted them in the Southwest, hoping they would produce adequate (read: marketable) fruits. Soon, however, they discovered a problem that growers in the Middle East, who had cultivated date palms for thousands of years, were well aware of.

Seedlings (plants grown from seeds) often differ from their predecessors, resulting in fruits of various sizes, shapes, and tastes. Commercial agriculture, which is built on uniformity, predictability, and standardization, cannot rely on seedlings. Luckily for the boosters, date palms are also capable of vegetative (sometimes called asexual) propagation. Mature palms sprout tiny offshoots from their base. These suckers are genetically identical to the mother tree and can thus be cut and replanted, serving as the perfect building blocks for every new grove.

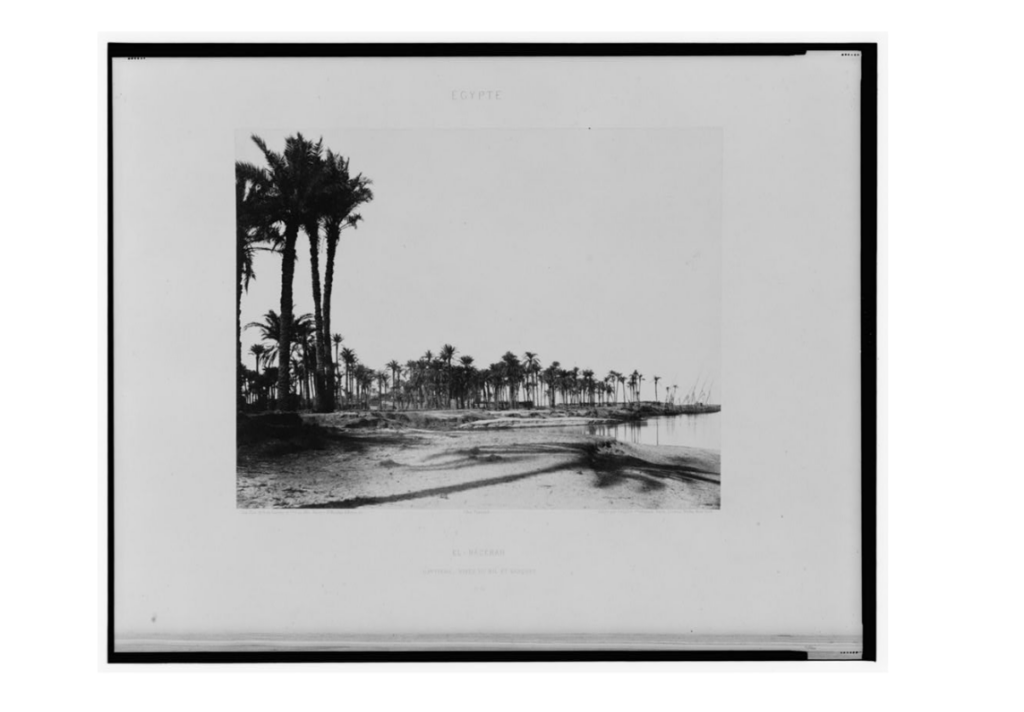

At roughly the same time, the Secretary of Agriculture, James Wilson, established the Section of Seed and Plant Introduction (SSPI). This USDA sub-division sent federal agents to various locations around the globe to collect new plants suitable for commercial cultivation in America. Some plant explorers, like Walter Swingle and David Fairchild, were also date boosters, fervently supporting the new date sector. For example, Walter Swingle and David Fairchild traveled to Egypt, North Africa, Oman, and Iraq to look for the best date types. They cut (or, rather, oversaw the cutting of) offshoots and carefully shipped them to agricultural experiment stations across Arizona and California. Overall, plant explorers imported several thousand offshoots during the early 1900s.

However, only a few of these made their way to local cultivators. This was not because of a lack of demand. With the expansion of offshoot importations, farmers around California and Arizona grasped their economic potential and contacted boosters, asking for a piece of the cake. During the early 1900s, dozens of farmers reached out to the agricultural experiment station at the University of Arizona, begging for some offshoots. But boosters refused to share their precious biological repository and preferred to keep offshoots for their experiments. Robert Forbes, the head of the station and a leading date booster, refused all farmers’ requests, offering prospective farmers to take the uncertain path of seedling cultivation. Boosters, who realized the economic importance of imported offshoot, began entrenching their monopoly over the young industry, deciding de facto who got to grow dates and who did not.

Date boosters also used their political power to prevent prospective farmers from privately importing offshoots. They feared that unregulated importation would risk the purity of their slowly growing biological repository by introducing subpar types to the Southwest. Even worse, some feared that private importers would lay their hands on some prime types, fostering an over-importation boom that would shake up the entire juvenile sector. In short, date boosters had an effective monopoly over offshoots importation and no desire to share power with anyone deciding to challenge it.

Some nevertheless tried. Bernard Johnson, a farmer from Walters, CA, dreamed of importing and selling offshoots by himself. In May 1902, he contacted Forbes, asking for his advice. Forbes tried to dissuade Johnson, arguing that offshoot importation was expensive, way beyond the layperson’s abilities. “Most of us,” he wrote, “will have to wait until Uncle Sam is ready to help us out.”[1] Johnson abandoned his plan for a while, only to renew it two years later while working for the newly established governmental date orchard in Mecca, CA. But traveling to the Middle East would take at least three months, and Johnson’s supervisors frowned upon his intention to leave the Mecca Garden for such a long period. They contacted Forbes, asking him to convince Johnson not to go. They also threatened Johnson that if he decided to leave, the federal government would sell the deed on his small ten-acre property to the local land development company. Following these threats, Johnson decided to leave the Mecca Garden for good, writing to Forbes, “I am very sorry indeed that I entered the employ of the Department of Agriculture.”[2] Even after he left, Johnson’s supervisors showed no mercy, cutting his plot from the nearby government well, forcing him to spend roughly $750 on digging a new well and setting new irrigation lines. All because he dared to challenge date boosters’ monopoly.

Ostracizing Texans

California’s hot climate is ideal for date cultivation, and it is no wonder that the American date palm sector prospered there. Why did places with similar climates – like parts of Texas, Nevada, or New Mexico – never become major date production centers? One possible explanation has to do with California agriculture more generally. From the mid-nineteenth century, the temperate climate in the Central Valley drew investors and made the Golden State a global agricultural hub. When date palms joined the party, many investors were looking for a way to capitalize on the country’s prospering gardens and were willing to invest in new projects. But there is more to that story. Much like Bernard Johnson’s case, date boosters blocked any attempts to challenge their monopoly, even if it meant actively going against other government agents.

In 1904, Harvey Stiles, a state horticultural inspector from Corpus Christi, Texas, traveled to the St. Louis World Fair, where he probably visited the new exhibit on date palms, courtesy of our old friend Forbes. Upon his return to Texas, he witnessed “date trees at fully half a dozen points, from Bee [he probably refers to Bee County, A.D.] down the coast to Corpus Christi and Brownsville and up the river valley, all looking well.”[3] Stiles began studying these trees and their adaptability to the south Texas climate, documenting local date cultivation along the Rio Grande and traveling to Mexico to secure pollen that would later serve him to pollinate local palms manually. Stiles then began canvassing for establishing “a plant laboratory, or whatever name it may carry” to develop a date palm industry in Texas. He dreamed of dethroning California and Arizona and cementing the Lone Star state as the new American date capital.

But boosters were not ready to share their resources and knowledge with other people. Walter Swingle, who was recently described as a central figure in developing date cultivation in Texas, [4] saw the potential in Western Texas’ climate, writing that “the lower Rio Grande… is a fair prospect of growing third-class dates in bulk to be sold in competition with the Persian Gulf dates now imported into this country in enormous quantities.”[5] At the same time, Swingle was more reluctant to include Texans in the date bonanza, arguing that only experienced people (read, his associates) should monitor prospective cultivation. Needless to say, Stiles was not the experienced person Swingle had in mind.

Alternatively, Swingle suggested appointing a USDA arboriculturist named Silas Mason to survey the true potential of southern Texas. “It is important,” Swingle concluded, “That this work [of promoting date-related science and production in Texas, A.D.] be done by us and that these plants are not handled by Stiles who can pervert the facts to suit his pursuit.” [6] While the federal government went on to experimenting with date cultivation in Laredo and building a pest-free date farm in Weslaco and Winter-Haven, Stiles was left out, selling seedlings from his private nursery.[7] Texas, who shone momentarily as the next big thing in date cultivation, never became a leading producer. Just ask anyone who has ever eaten a date grown in Texas.

Southern California became the country’s leading date-producing region thanks to its favorable climate and because the people who laid the industry’s foundations made sure to eliminate all competition from the get-go. That does not mean we should castigate or diminish their significant contribution to American agriculture. Instead, we should acknowledge the messy, awkward, and exciting histories of date cultivation and use them to reveal the political intrigues that shape food production. Date palms thus provide an excellent perspective into the history of fear and loath in the desert and an excellent gateway to larger questions of production and power.

Atar David is a Ph.D. candidate in the History department at UT Austin and the Associate Editor for Not Even Past. His dissertation research focuses on the circulation of agricultural commodities and agronomic knowledge between the Middle East and the American Southwest from the late nineteenth to the mid-twentieth century. Together with Raymond Hyser, Atar founded the “Material History Workshop” – a bi-monthly graduate workshop centered around material culture. You can read more about the workshop here: https://notevenpast.org/uts-material-history-workshop/

[1] Forbes to Johnson, 5.31.1902, University of Arizona Special Collections, AZ 406, Box 11, Folder 6.

[2] Johnson to Forbes, 11.16.1904, University of Arizona Special Collections, AZ 406, Box 11, Folder 6.

[3] “Stiles to Wilson,” 5.14.1906, Date Palm Collection (MS 047) Box 2, File 40, Special Collections & University Archives, University of California, Riverside.

[4] Dennis Johnson and Jane MacKnight, “Date Palm Growing in South Texas,” PalmArbor, 2022.

[5] “Swingle to Galloway”, 10.19.1906, Date Palm Collection (MS 047) Box 2, File 40, Special Collections & University Archives, University of California, Riverside.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Johnson and MacKnight, “Date Palm Growing in South Texas,” 11–20.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.