By Fernando Gomez Herrero

This is the first half of a two-part article. To read the second part, click here.

Anthony Pagden is a Distinguished Professor in the History Department at the University of California-Los Angeles. England-born and Oxford-trained, but based on the West Coast of the United States, he is emotionally and intellectually invested in the idea of Europe–that is, in the coherent continentalism that is also the current project of the European Union. This is also, in his case, the continent-wide project of liberal democracy that must respond convincingly to the still-unfurling disappointment of Brexit. Pagden addresses this project in relation to a new book, The Pursuit of Europe: A History (2022). This work is connected with an edited collection of essays, The Idea of Europe: From Antiquity to the European Union (2002). Both works cover vast time spaces and aspire to lofty goals, encompassing perhaps more continuities than discontinuities.

Pagden’s scholarship began with a focus on the Early Modern and Colonial legacies of the Hispanic Empire, starting with Hernán Cortés’s Cartas de Relación. Pagden addressed this topic in The Fall of Natural Man: The American Indian and the Origins of Comparative Ethnology (1987). His other works include Peoples and Empires (2001); Worlds at War: The 2,500-Year Struggle Between East and West (2008); and Burdens of Empire: 1539 to the Present (2015). Pagden is also the author of The Enlightenment: And Why It Still Matters (2015), although the title was not one of his choosing. All of his work is concerned with huge (imperial) units, examining the coherence of continentalism, the gravitational pull from the 16th century towards the tradition of the Enlightenment and beyond, and the open embrace of the ideals of liberal universalism. Pagden remains to this day a committed representative of the British school of international thought, and he defends the validity of a history of ideas “from above.”

Earlier this year, Pagden sat down for an interview with Fernando Gomez Herrero, an historian based at the University of London’s Birkbeck College. In conversation with Gomez Herrero, he grappled with questions such as: how does a political configuration such as Europe come into being? How does it overcome enmities and divisions? What type of internationalism does it embrace? What are its limits? And whom do those limits classify as “others”?

The following article–Part I of II–reproduces Pagden’s answers to questions about the intellectual priorities and scholarly methods that informed his vision of Europe. For a discussion of that vision itself, click here to read Part II.

EDITOR’S NOTE: The following interview has been lightly edited for clarity’s sake.

Fernando Gomez Herrero: How do you situate The Pursuit of Europe with respect to the rest of your scholarship?

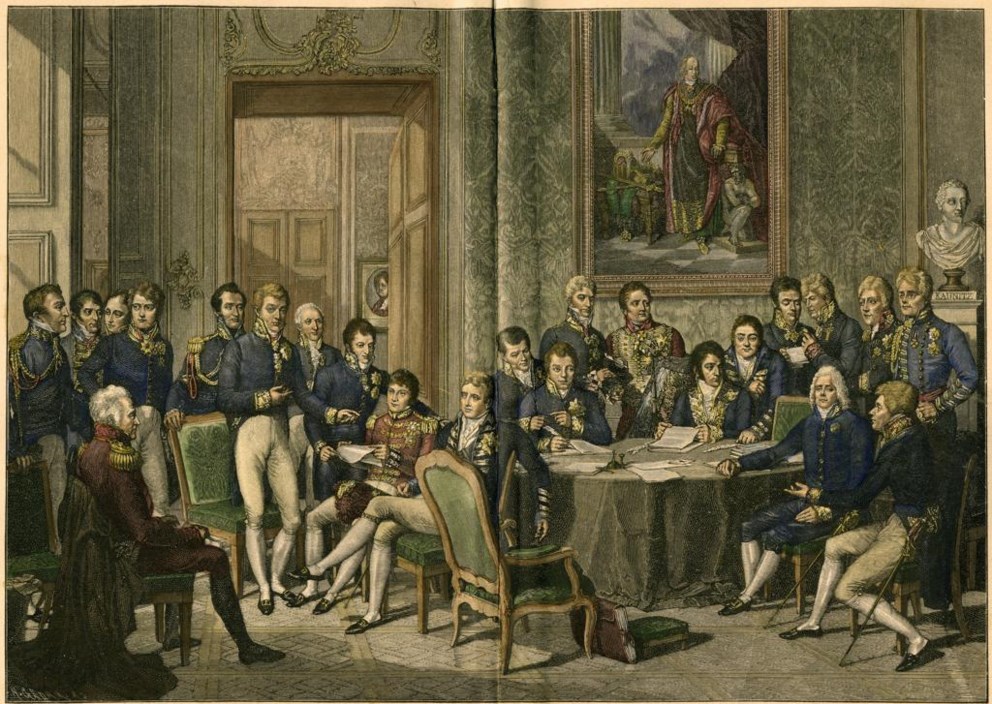

Anthony Pagden: Modern Europe is not an empire, but it is an aggregate of states. It is a congregation of peoples. I think that is partly what I have been looking at. I was looking at the way Europe was looking at the outside world, the way that Europe responded to the outside world, and the creation of the idea of the unification of Europe is also part of this idea of the European domination of the world. The whole point of the third chapter in the book was how significant the European experience of empire was for the creation of the idea of European unity. Now, there has been a lot said about that, but it is usually to say: “Oh, well, the EU is nothing other than another imperial project”; or, “It is a way the Europeans are trying to hold on to their imperial past after 1945, to hold on to what was left of their imperial possessions.” Now, there is evidence to suggest that that is partly true. But that wasn’t what interested me. What interested me was the way the experience of empire and the reflections upon empire, for instance, particularly in the late 19th century led to, fed into–put it this way–a desire, a belief in the possibility of a greater coherence between the peoples of Europe that starts after the end of the Napoleonic wars in 1815. It is an interesting period, which goes from the collapse of the last attempt before Hitler (if you take Hitler’s to be another such project) to create an empire within Europe. And then, out of the demise of Napoleon, came the “Congress System” and the “Concert of Europe,” a routinized series of international conferences which is really the first attempt to bring the “great powers” of Europe together into an alliance of states. This is, in a sense, where the story begins. There were earlier versions in the Enlightenment, but they were much more–how to say it?–detached from reality. Voltaire said there were “chimera” that “could no more exist among princes than among elephants and rhinoceros, or wolves and dogs.” That’s what the Enlightenment schemes for European unity were, structured fantasies. But a real political project of unification really only begins in 1814-15 with the Concert of Europe and the Treaty of Vienna, which ended the Napoleonic wars. Everything moves forth from there.

Then came the First World War, which saw the collapse of all the major empires from within Europe (the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Ottoman Empire, and so on), and out of that we get the idea of the world of nation-states that begins in 1919. This is really the crucial moment in recent European history. It is the Paris peace conference of 1919 that creates the idea of self-determination, which then leads eventually to the collapse of European overseas empires and an attempt to reconfigure the idea of Europe in such a way, partly as the critics say, in order to preserve as much of the overseas empires as possible–that is perfectly true–but also to try and bring this together in order to create a more coherent world. For embedded in the Covenant of the League of Nations were a series of attempts to try to create a prototype of the European Union. This all, of course, collapses in the 1930s.

My interest in the idea of European unification started with The Idea of Europe: From Antiquity to the European Union, which is a collection of essays that I helped organize with colleagues in Washington. (We also came together at a conference in Washington.) We were writing about the conception, the “idea” of Europe. But that concern had always, in a sense, been in the back of my mind, because if you think about the contact between the Hispanic world and Amerindians, for instance, it was not just that the Spanish were thinking in terms of: “There are indigenous peoples out there and they are barbarians and so on, and we are Spanish, etc.,”; it was much more than that. It was not just Spain, it was Europe. When [the Spanish Renaissance philosopher and theologian] Francisco de Vitoria, for instance, talks about Christians, what he is talking about is not just the Spanish. He is talking about the whole European world. Then, I also had a broader interest in ways of [dealing with] the international. How do you cope with the relationships between states, how do we conceive the borders between the nation-states, and [between] peoples? My next book will be precisely about that: how do you deal with the international particularly in the modern world? That, if you like, is the underlying theme of everything I now do.

FGH: What do you want to accomplish when you historicize?

Pagden: That is a big question. What do I want to accomplish? I want a better understanding of where we stand, and I suppose of where we might be going, what might be the possibilities for the future. Going back to your previous question about America and the Americas, one of the things about that is that I am an absolutely convinced cosmopolitan internationalist. I have a strong distaste for any form of nationalism and sectarianism and parochialism, whether it be cultural, linguistic, moral or political. I might say I have a neo-Hegelian view of the progress of humanity. If you look at the history of these things, we have gone from empires to nation-states and these nation-states are dissolving into other forms of union, but the development from the primitive hunter-gatherer of pre-antiquity has always generally been forwards. It is not a steady progress by any means, it goes backwards and forwards, but if you take it in millennia, it is the story of a progress towards the greater and greater unification of the human race. And that poses all sorts of problems about how you achieve that unification without turning everyone into the same sort of person inhabiting a vision of the universal as a place where everyone wears the same clothes and speaks the same language and so on. If you want to avoid that kind of science-fiction nightmare, then how do you go about breaking down the resistances of these smaller units? The contemporary one is the nation-state, but originally it was the family, the tribe, the kin-group, then it became parish, or commune, etc. How do you do that? What lessons can we learn from that? In my case, because I am a historian primarily, what lessons can we learn from the past about that?

FGH: Our moment is one of uncertainty, messiness and unpredictability–violence, too, blatantly in the case of Russia’s war in Ukraine. I do not detect many burdens, uncertainties and hesitations in your method of and belief in history. Is that a fair statement? is it a good thing? A bad thing?

Pagden: I think it is a question of what you choose to write the history of. Of course, you can do a Spengler [e.g., copy the pessimistic style of Oswald Spengler, a German intellectual active during the early 20th century] and write a history of disaster and lots of people have. There are accounts of Europe that are simply a manifest of one disaster after another. For example, there’s Mark Mazower’s Dark Continent: Europe’s Twentieth Century (1998), a very brilliant book that brings out all sorts of things like the fact that no one would have guessed liberal democracy would triumph after 1945. We were facing a Europe that was either Fascist or Communist. By focusing on that chaos and confusion, he has come up with a picture of the European continental divide which I find extremely illuminating. But the pessimists, the nihilists have nothing to offer other than pessimism and nihilism. They merely think–or claim to think–that everything is going to hell in a handcart. I think these things are projects: the pursuit of Europe is a pursuit. We have not got there yet. This is the history of a project which is still going forward. It might yet fail. But I am not one of those who would write a book about “The Light that Failed, The Europe that Failed, The End of Europe.” There are enough of them around. Some of the claims they make are perfectly valid. I think you are right in the sense that the bottom line is that I believe in it, in the EU that is: I think it will succeed, or go on succeeding. To say “succeed” suggests that there is an end goal, and we can only do our best, not as individuals, but as historians, political scientists, and so on: to lay out the base plan, to show how it has come about, to show where it is going, to offer some sense to what that future might be.

FGH: In The Pursuit of Europe, you mostly trace “history from above,” documenting the assertions and good intentions of elite groups as they are fighting with each other for hegemony on the European stage. Do you see them as makers of an “order” that “we,” the people, mostly follow?

Pagden: That is a good point. Yes. The making of order: I like that. I think that’s right. I would say that I am an intellectual historian. Which is history from above. I lived through the period of the 1970s-1980s when it was very fashionable to think in terms of “history from below.” I was for a while quite a good friend of Carlo Ginzburg, one of the shakers and movers of the “microhistory” movement and a brilliant historian. I knew him in Italy and when I had a position in Florence at the European University Institute and then later at UCLA. In the early 1980s, “history from below” was very much the fashion. I was never much attracted by it. I am not saying it is not valuable. I am not saying at all it was not interesting and some of the books it produced were fascinating, particularly Ginzburg’s and those by a close colleague, Carlo Poni, whom I had also known in Florence. But my theme and my interest was always “history from above.” Elites are those who have ideas. The common people, sorry to use that phrase, don’t. I mean, that is not where ideas come from. Those ideas, I believe very strongly, are what shapes and forms our political behavior, or behavior in general, even if we are not always aware of them. I belong to a Department of Political Science, which means that for the exception of three other people and one or two fellow travelers, most of my colleagues are people who are concerned with counting things. So, they don’t really know how ideas fit into this because their ideas are always very simple. “If you do this with voting practices, what result do you get and so on?” My claim has always been: “Very well, I am not saying that this is not a valuable exercise, and it is very useful in actual policy making. What I would claim, however, is that most of the terms they are discussing derive from theories and ideas in a broader sense which have a historical past, and it is those ideas that I am concerned with.” If you want to persuade people to vote on the Left, for instance, and you come up with an equation that tells you that if you offer them health care they are more likely for the Right, you have to know what these terms mean to start with. You have got to know how you have ended up in a world in which we are divided in this way. When I teach undergraduates, I am always telling them: “Do you want to know how you got to be where you are, your way of thinking, the way you are thinking now, the impact, for instance, which this thing called ‘the Constitution’ has on you? Then you have to go back and find out how it was constructed, find out where it comes from, otherwise you will not understand properly the nature of the material you are dealing with.” So, I think we have a very important role to play in that respect.

FGH: What type of historian are you? You are a historian of international ideas. But, for example, religion does not interest you as much. You are a secularist. And your ideas tend to be ideals towards the construction of what we might call “Western European togetherness,” which you call “Europe” and equate to a liberal multicultural society. You are not dwelling on ideas of extermination, for instance.

Pagden: That’s true, roughly speaking. In The Enlightenment: And Why It Still Matters (which is not, by the way, my title, and I don’t very much like it), I made an attempt to understand the significance of the Enlightenment for the West and the West as it expanded beyond the perimeters of Europe. The good and the bad. Where does it come from? What do you want to preserve of it? There are those who don’t want to preserve any part of it. I am not going to deny that. But then there are a great many things that we do wish to preserve and liberalism is one of them. Not “neoliberal’ but “liberal,” certainly in the sense that John Stuart Mill understood it. You take on board whatever everybody can bring and you judge that according to whatever set of universal standards and principals of pain and gain apply. It is a form of utilitarianism. And that is what we must be moving towards. And I think that can only be done at an international scale rather than a national one. Nationalism can only give us things like ISIS, and so on. Europe was, for me, the stepping stone.

There was another aspect to writing that particular book. By the time I started, Brexit was underway. But I am old enough to remember when Britain first joined the EU, and I was one of the people who voted in the original referendum on continuing membership in 1975. That was the moment when many of us thought that a new world was approaching. We had behaved honorably between 1939 and 1945. (We might not have done. Britain might easily have gone the way of Vichy France. Lots of people at that time wanted that). But now, it was time to create a new world: a new world not just for my generation, which is already now old, but a new world for the generations that were to come after. And that world could not be an attempt, as Churchill was attempting immediately after the war, to reclaim the best of English 19th-century colonialism and rebrand it as some sort of Commonwealth in which the British stood “with Europe but not of Europe,” as he put it, a very nice phrasing (borrowed from Shakespeare). It captured very much what he and his generation wanted. But not ours. There was that moment in the 1970s when there was the feeling that all of that has now been put behind us and now we were going forward into another world. Britain, however, was always very sluggish about it. It never acted with the enthusiasm that ,for example, Spain did when Spain joined the EU in 1992. I remember very well because I had Spanish friends on both sides of the political divide who were saying, again, their problem was not World War II, their problem was Francisco Franco. They said, essentially, that “in order to go forward, we have got to change and we have got to be part of this modernizing project, and the only way to be part of this modernizing project is to reconstruct ourselves.” Britain had, in a sense, done much the same thing twenty years earlier, but at one point in time it had lost momentum. But then, when Britain joined, “Europe” was very much a Common Market. Admittedly, the founding treaty of the European Coal and Steel Community of 1952 speaks of the ambition to create a “United States of Europe.” Even so, the Common Market did not yet have the political ambitions that it acquired later, particularly after the fall of the Berlin Wall and the opening up to the East, which changed the nature of the political project. So, I really wanted to write this book, but I wasn’t sure anyone was going to read it.

FGH: Within what framework are you constructing “Europe” in the book? Would you pick international history? Intellectual history? Does the notion of “global history” appeal to you? Do you take Area Studies into account? It seems to me that your vision of “Europe” is the symbolic space where you want to be and which you want to occupy.

Pagden: Yes, absolutely. In answer to your question, I would say, first of all, that the history I am concerned with is intellectual history. It is international, but it is international only in the sense that I am not dealing with just one country. I don’t know of many people who do one particular history in one particular language. Basically, most intellectual historians are prima facie at least international historians. I certainly believe in that, since the people I study, for the most part, from the 16th century on, were internationalists. So I, too, have to be internationalist. You will not find anybody of interest who stayed at home. (Well, Kant, of course, stayed at home, but he read a lot and communicated a lot with other people.) Your mind at least has to travel, even if you as a person don’t travel.

Global history: yes. I am very interested in global history. As I said, Europe is for me but one part of a process. Some of the books in the past have been, I suppose, much more concerned with what one might call “global history.” There are all sorts of technical problems with global history. Most global history is, I don’t want to say, superficial. That sounds extremely condemnatory. There are people like Jürgen Osterhammel, of whom I think very highly, who is, for example, a historian of Asia, but who writes such that “global” history is always viewed from Asia. My case is Europe. It always comes back to Europe. But that does not mean that I am not interested in and conscious of all of the other parts of the world. Then, there is the question of international relations, but understood as the relations between the different parts of the world and how they fit together. So, yes, it is global in that sense.

Area Studies I associate with something that is now passé. I am certainly not that. I mean, there was a time in the 1970s-80s when I was vaguely associated with Area Studies for Latin America, but, again, I don’t think of it that way. If Latin America or Europe are interesting to me, ultimately it is because they are connected to a wider world. The study of the development of Europe, the pursuit of Europe, ultimately remains interesting because there is somebody out there beyond it. Now, you are right in saying it is my “home.” I think of myself as a European. I do not think of myself as British. I am not unusual in that, particularly [since I do not live there anymore]. I have two children who live in Britain, but I don’t go back very often. I find London stranger now than I ever did. I used to be able to have a meal for £5. Now I cannot get a glass of water for that money (laughter). So, there are changes. There are those wonderful stories of Joseph Conrad of people returning “home” and then not recognizing where they are. For me, “home” does not exist any longer. Probably, Paris. This is purely personal. But my intellectual home is Europe.

FGH: Tell us about your next book.

Pagden: I have written, and it is about to be published in Italian, a book which is called Oltre gli Stati. Poteri, Popoli e Ordine Globale–“Beyond the State: Powers, Peoples and the Global Order.” It is basically about the internationalization of the world. It starts off with a historical account–I am a historian–of how I think the “international” space came together. The two major spheres of that are the commercial enterprises of the European states, above all in the 18th and 19th centuries, and the creation of empires. So again, we go back to that form, and the creation of an international legal order. Then I go into what is partly touched on in The Pursuit of Europe, which is the history of federalism, because what I want to argue briefly is that if the world has any future, it lies in some form of federalism. This is interesting, not least of all because forms of federal government exist universally. They are not just European. True, a whole system has been developed, which is European in origin, going all the way back to the Amphictyonic League in Ancient Greece, but they are by no means exclusively European. What I look at is the ideas that lie behind federations in India, Simón Bolívar’s “amphictyonic” Gran Colombia in Latin America, and of course in North America to some extent. I am talking about “federalism,” as it was then called, and not federal states as such. The UK and Spain, Canada, and Germany are federal states in the latter sense. In fact, 82% of the world nations are federal states, technically. But I am talking about federations, groupings of states that come together and what that future might offer. It is quite a short book. It belongs in a series, which is about what the West has contributed to the rest of the world. I want to develop that into some more sustained study of the federation and what its future might be.

Fernando Gomez Herrero: FGH (PhD (Duke University), MA (Duke U, Wake Forest U, U of Salamanca), B.A. (U of Salamanca; fernandogherrero.com) has lately taught at the U of Birmingham and Manchester in Britain. He has also taught at Duke U, Stanford U, U of Pittsburgh, Hofstra U, Oberlin College in the U.S. Latest work: “About the philosophical proposal of the Liminal Being (An Interview with Eugenio Trías Sagnier): eHumanista (Vol. 53, 2023): pp. 410-485; https://www.ehumanista.ucsb.edu/sites/default/files/sitefiles/ehumanista/volume53/ehum53.trias.pdf; ”Sobre postcolonialismos maltrechos, descolonizaciones malogradas y angostamientos universitarios,” Revista Umbral: Un Mundo en Crisis y Las Humanidades: Sus Retos y Futuro (Universidad de Puerto Rico): Vol. 18, Diciembre 2022) & “The Latest American Appropriation of Western Universalism: A Critique of G. John Ikenberry’s “Liberal International Order,” (http://journal.thenewpolis.com/archives/1.1/index.html . There is an extensive engagement in Spanish with The Crisis of American Foreign Policy: Wilsonianism in the Twenty-First Century, edited by Ikenberry et al (Princeton UP, 2008): “Sobre la crisis oficial de la política exterior estadounidense en las primeras décadas del nuevo siglo” (Nuevo Texto Crítico, Vol. XXIII, No. 45/46): 25 pp. There is a forthcoming article titled “Foreign Humanities and “the liberal West” in the Anglo Zone in the Interregnum: A Critique of G. John Ikenberry’s “Liberal Internationalism,” a synopsis of which was presented at the Conference Legacies organized by the Universitat de Barcelona in June 20-22, 2022 (Home – English – Legacy Conference’ 22 (ub.edu)).