“Muhammad’s Law” in Latin America invites readers to explore Islam in the early modern Iberian Atlantic—a historiographical field examining the interconnected histories of Islam across the Atlantic world. It is rooted in the lived experiences of Muslims who crossed the ocean, the metaphorical uses of “Muslimness” in Iberian colonial thought, and the material and intellectual legacies of the Islamic world that shaped the Americas. The six foundational books discussed here seek to disrupt traditional narratives of Atlantic history and highlight Latin America as an active participant in global modernity, shaped by cultural exchange and intellectual collaboration.

This exploration is a deeply personal one. My fascination with the legacies of Al-Andalus and the Middle East—metaphors for an Islamic continuum linking Spain, the Maghreb, the Sahel, and the Levant—has profoundly shaped how I understand the Americas. This intellectual journey began with my first reading of Albert Hourani’s A History of the Arab Peoples, a book that sparked my passion in history. The possibility of connecting the stories of Islam to Latin America captivates me, as it reframes the region as a global crucible for understanding modernity.

Al-Andalus, with its imperfect but real interreligious coexistence, continues to challenge us to rethink Latin America’s colonial history—not only as a story of vertical oppression but also as one marked by the incorporation of cultural difference, often through contested processes. These Muslim legacies, often referred to as alborotados (noisy and persistent), remain subtly yet powerfully visible in ways we often overlook. They complicate our understanding of the complex interplay between Christianity, native cultures, and the specters of Islam in the Americas. The following books, central to my comprehensive exams and my master’s thesis, The Alborotado Caribbean: Archiving Rowdy Gentes and Specters of Islam in the Long 16th Century, have helped me unravel these connections and reveal a more complex and interconnected Atlantic world.

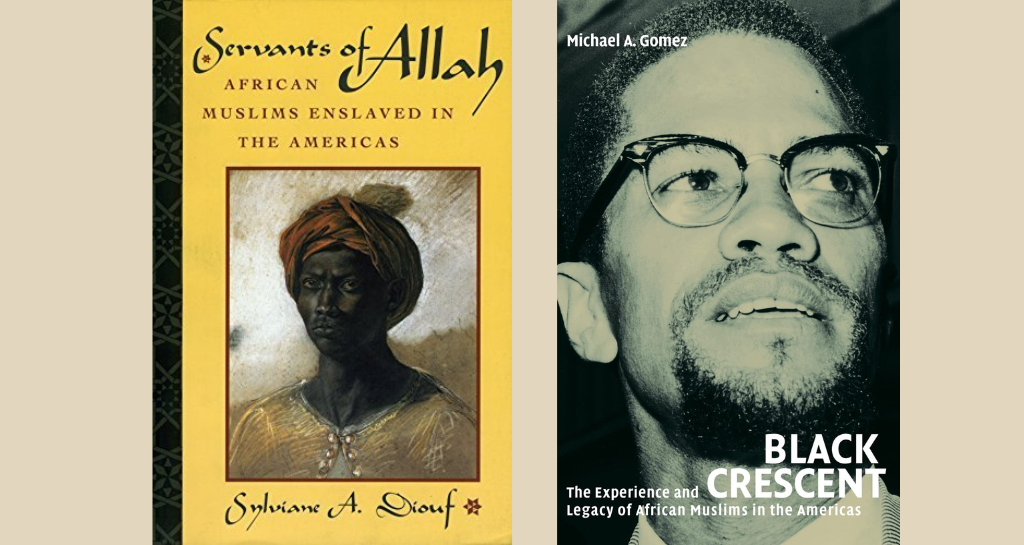

African Muslims and the Atlantic World: Sylviane A. Diouf and Michael A. Gomez

Together, Sylviane Diouf’s Servants of Allah: African Muslims Enslaved in the Americas (1998) and Michael A. Gomez’s Black Crescent: The Experience and Legacy of African Muslims in the Americas (2005) provide a comprehensive exploration of the role of African Muslims (mainly Wolof, Mandinka, and Fulbe) in shaping the Atlantic world. Diouf’s work emphasizes the resilience of Islamic faith and practices among enslaved Africans, while Gomez extends the discussion to encompass the broader social and cultural legacies of African Muslims across the Americas.

Diouf’s study highlights the enduring presence of Islam in West Africa, particularly in Senegambia, and how it influenced the identities of enslaved Muslims who crossed the Atlantic. Her meticulous analysis of primary sources, such as colonial decrees and inquisitorial records, reveals how African Muslims preserved their faith through practices including the use of protective talismans, dietary restrictions, and acts of resistance, such as the 1522 Wolof rebellion in Hispaniola (Enriquillo’s revolt). Diouf positions Islam not merely as a religion but as a framework for resilience and cultural survival in the face of dehumanizing conditions.

Gomez builds on this foundation by situating the experiences of African Muslims within a broader historiographical context, incorporating both Latin America and the United States. The narrative spans from West Africa to the Americas, examining how Islamic traditions adapted to different colonial contexts. For instance, Gomez explores how African deity names containing the particle Allah such as Ọbatala, the presence of Marabouts (Sufi holy people) and the practice of Taqiyya (religious dissimulation) facilitated the survival of Islamic practices in the early colonial Americas. He also delves into the intersections between African Islamic traditions and syncretic religions in the Americas, such as Lukumi in Cuba.

Both authors underscore the significance of African Muslims in shaping the cultural and religious landscapes of the Atlantic world, but they also diverge in their emphases. Diouf focuses on cultural retention and the religious practices of enslaved Muslims, while Gomez extends the discussion to the legacies of these practices, particularly in North America. Together, these works correct a long-standing historiographical neglect by emphasizing the centrality of African Muslims to the history of the Atlantic world. They reveal how Islamic traditions, both as faith and cultural practice, shaped the identities, resistance practices, and legacies of enslaved Africans and their descendants across the Americas.

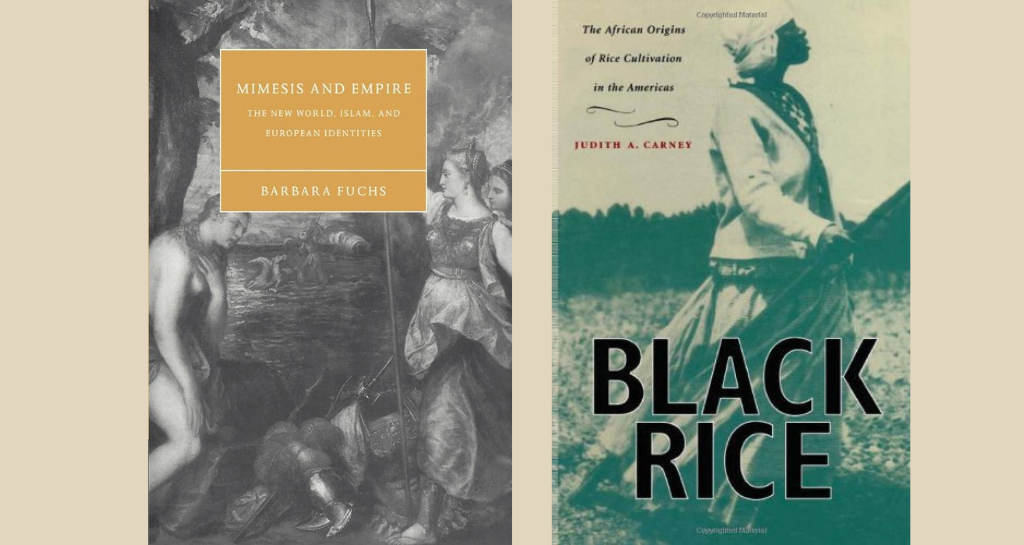

Dialogues Between Symbolic and Material Legacies: Barbara Fuchs and Judith Carney

Barbara Fuchs’ Mimesis and Empire: The New World, Islam, and European Identities (2001) and Judith Carney’s Black Rice: The African Origins of Rice Cultivation in the Americas (2001) approach the legacies of Muslim cultures in the Atlantic world through distinct yet complementary lenses. Fuchs examines how symbolic anxieties about Islam shaped Spanish colonial ideology, while Carney focuses on the environmental and agricultural transformations that were driven by the knowledge and practices of African Muslims. Together, these works demonstrate how the material and symbolic practices descended from Muslim people endured and adapted in the Americas, persisting despite colonial efforts at erasure and invisibilization.

Fuchs focuses on the literary and ideological constructions of “Muslimness” in Spanish colonial thought, showing how Spain’s long history of conflict with Islam informed its treatment of indigenous peoples and other non-Christian groups in the Americas. Her analysis reveals how anxieties about Islam—rooted in centuries of confrontation with Muslim powers in Iberia and North Africa—were projected onto the New World. Drawing on literary works such as Alonso de Ercilla’s La Araucana and Lope de Vega’s La Dragontea, Fuchs illustrates how Spanish authors used the figure of the Muslim in the Indies to articulate fears about rebellion, idolatry, and cultural otherness. For example, Ercilla’s portrayal of the indigenous Mapuche in La Araucana draws on tropes of Muslim resistance, likening indigenous leaders to Morisco rebels. Similarly, Lope de Vega conflates Protestant and Muslim enemies in La Dragontea by portraying Francis Drake and his crew as “Dracárabes” (Drake-Arabs). These representations reveal how Spanish anxieties about Islam shaped their perceptions of all non-Catholic groups, blurring the lines between religious, cultural, and political adversaries. Fuchs’ reliance on literary sources underscores how deeply embedded these anxieties were in Spanish intellectual and cultural production and demonstrates how the symbolic legacies of Muslimness were instrumental in shaping colonial narratives of conquest and suppression.

In contrast, Carney’s Black Rice foregrounds the material and environmental impact of African Muslims, particularly through their agricultural knowledge and practices. Carney highlights how enslaved Africans from Muslim regions of West Africa, especially Senegambia, brought sophisticated expertise in rice cultivation that transformed the landscapes and economies of the Americas. The rice of Senegambia was a clear expression of the Old-World interconnectedness provided by the Islamic world, from East Asia to West Africa. We cannot think about the typical Caribbean diet nowadays without considering the importance of this rice agricultural knowledge brought by Senegambians. The cultivation of rice, a crop long associated with Islamic agricultural traditions, became central to the economies of South Carolina, the maroon communities of Brazil, and other Atlantic regions. By adapting their agrarian knowledge to new environments, these enslaved peoples ensured both economic viability and cultural continuity. Carney’s work challenges Eurocentric narratives of the Columbian Exchange by revealing the critical role African Muslims played in shaping agricultural landscapes, effectively redefining the Americas as spaces marked by their contributions to environmental knowledge.

While Fuchs reveals how Spain’s anxieties about Muslims were projected onto indigenous peoples and other colonial subjects, Carney demonstrates how African Muslim agricultural expertise reshaped the ecological and economic foundations of the Atlantic world. Together, these works highlight the dual dimensions of Muslim cultural legacies—symbolic and material—and how they endured even in the presence of colonial systems that sought to suppress them. By placing Fuchs and Carney in dialogue, we see a fuller picture of how Muslim-descended peoples and traditions intersected with colonial life. Whether through literary anxieties about rebellion and heresy or the cultivation of rice fields that sustained enslaved communities, these legacies remind us of the profound ways the Islamic civilization influenced the Americas.

Muslim Identities in Individual Flux and Collective Stasis: Karoline Cook and Karen Graubart

Karoline Cook’s Forbidden Passages: Muslims and Moriscos in Colonial Spanish America (2016) and Karen Graubart’s Republics of Difference: Religious and Racial Self-Governance in the Spanish Atlantic World (2022) offer two different but complimentary perspectives for understanding the dynamics of Early Modern Atlantic Islam. Cook emphasizes the forbidden mobility of individuals marked by “Muslimness” (Turks, Arabs, Berbers, Moriscos, and West Africans), while Graubart focuses on the stasis and semi-autonomy of disenfranchised communities (Jews, Moors, Indians, Africans) within the framework of the Spanish Empire. Together, these works illuminate how both individuals and institutions navigated and reinvented the imperial Atlantic, showcasing microhistories of personal adaptation alongside broader histories of collective self-governance.

Cook’s exploration centers on the movement of Moriscos and other Muslim-marked individuals within the Spanish Empire, particularly their migration to the Americas despite legal prohibitions. Her work uncovers how individuals circumvented colonial restrictions, forging paths that challenged the rigidity of imperial legislation. Through inquisitorial records mainly from Mexico, Cook reveals the liminal spaces these individuals occupied, adapting between Muslim and Christian identities while carrying memories of their prayers in Arabic and material markers of faith, such as talismans and amulets. This “forbidden mobility” underscores the agency of individuals navigating the Atlantic system, even as their movements were surveilled and constrained. Cook’s narrative highlights how the specter of Muslimness shaped the legal, social, and rhetorical frameworks of the empire, with Moriscos often cast as symbols of contamination or rebellion—anxieties that were projected onto indigenous uprisings in the Americas.

Graubart, in contrast, shifts the focus from individuals to communities, examining how disenfranchised groups used the institutional framework of the república to assert forms of self-governance and negotiate their place within the imperial system. By analyzing urban spaces and corporations in Seville and Lima, like alhamas (Moorish communities), cofradias de negros (Black brotherhoods), and Indigenous pueblos, Graubart demonstrates how the Spanish Empire operated as a constellation of overlapping jurisdictions, where legal pluralism allowed for a limited collective autonomy (working as republics). Her use of GIS mapping to study the spatial organization of these communities reveals how they adapted imperial institutions to maintain cultural and religious identities while asserting their collective needs. This framework of collective semi-autonomy contrasts with Cook’s focus on individuals facing persecution or concealing their Muslim identity, highlighting two distinct ways marginalized populations engaged with the empire: through individual strategies of evasion or dissimulation, or by collectively adapting to imperial institutions to assert their communal presence.

By placing these works in dialogue, we see two sides of the same coin: the tension between mobility and stasis of identities within a proto-racial Atlantic world. Cook’s focus on individual trajectories reveals the fluidity and adaptability of particular identities, even in the face of systemic religious oppression. Meanwhile, Graubart’s analysis of micro-corporations highlights the endurance and reinvention of communal structures that facilitated collective action and cultural resilience. Both perspectives underscore how both institutions like the república and individuals traveled and transformed across the Atlantic, shaping the imperial world in reciprocal ways. The broader implication of this dialogue is a realization that the Atlantic world was not a monolithic system but a dynamic space of (re)invention of human difference. Institutions such as alhamas and cabildos evolved as they crossed the Atlantic, just as individuals like Moriscos navigated their roles within shifting social and legal frameworks. Cook’s microhistories and Graubart’s community-focused lens converge to show how Muslimness, both as a lived experience and a conceptual spectral category, was central to the development of the Spanish Atlantic world. Together, they offer a nuanced understanding of Early Modern Atlantic Islam, revealing how people and institutions alike negotiated the complexities of empire.

Final thoughts

The field of Early Modern Atlantic Islam opens a window into the complicated and interconnected histories of the Atlantic world. The works examined in this article collectively reveal how Islam shaped this world across multiple dimensions: through the resilience of African Muslims in the Americas, the metaphorical frameworks of “Muslimness” in Iberian colonial thought, and the tangible legacies of Islamic cultural, technological, and intellectual practices. Despite these contributions, there is much work to be done.

These six books disrupt conventional narratives of the Atlantic world as a space defined solely by European dominance. Instead, they reframe it as a region shaped by cultural intersections, shared histories, and dynamic reinventions of identity that go beyond the histories of a top-down successful Catholic spiritual conquest. They challenge us to recognize the complexities of Latin American colonial history, not merely as a story of exploitation and racialization but as one marked by contested incorporation by conversion or mestizaje, and transformation of difference—whether cultural, religious, or institutional. By tracing these legacies, we uncover shared histories that transcend cultural and geographical boundaries. From the rice fields of Senegambia to the “republican” institutions of Lima, these stories illuminate the interconnectedness of the Atlantic world and challenge us to rethink the narratives we take for granted. In doing so, we can see Latin American history was profoundly influenced by the specters and experiences of Atlantic Islam.

Additional Recommended Readings

- Deardorff, Max. A Tale of Two Granadas: Custom, Community, and Citizenship in the Spanish Empire, 1568–1668. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2023.

- Gruzinski, Serge. ¿Qué hora es allá? América y el Islam en los albores de la modernidad. Mexico City: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2015.

- Hamann, Byron Ellsworth. Bad Christians, New Spains: Muslims, Catholics, and Native Americans in a Mediterratlantic World. London: Routledge, 2019.

- Hourani, Albert. A History of the Arab Peoples. London: Faber and Faber, 1991.

- Rappaport, Joanne. The Disappearing Mestizo: Configuring Difference in the Colonial New Kingdom of Granada. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2014.

- Reis, João José. The Story of Rufino: Slavery, Freedom, and Islam in the Black Atlantic. New York: Oxford University Press, 2010.

- Schwartz, Stuart B. Blood and boundaries: the limits of religious and racial exclusion in early modern Latin America. Waltham: Brandeis University Press. 2020.

Acknowledgment

This reflection first began to take shape during the seminar “Islam in Europe and America” taught by Dr. Denise Spellberg, to whom I am deeply grateful for her generosity and encouragement to further explore these understudied and often overlooked connections. Dr. Spellberg has herself had the fascinating opportunity to examine some of these connections, particularly in relation to the United States, in her book Thomas Jefferson’s Qur’an: Islam and the Founders (2013)—a work that also contributes to broader efforts to understand the complex histories of Atlantic Islam.

Rafael David Nieto-Bello is a Ph.D. Candidate in History at The University of Texas at Austin and a historian from Bogotá, with a double bachelor’s in History and Political Science from Universidad de los Andes and a master’s degree in History from UT Austin. His research examines the intersections of the history of human sciences, race, religion, and the environment in the colonial Caribbean and the Atlantic world. He is currently writing his dissertation and working on digital humanities projects that analyze cartographic and textual representations of the colonial Caribbean.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.