NEP’S Archive Chronicles explores the role archives play in historical research, offering insight into the process of conducting archival work and research. Each installment will offer a unique perspective on the treasures and challenges researchers encounter in archives around the world. NEP’s Archive Chronicles is intended to be both a practical guide and a space for reflection, showcasing contributors’ experiences with archival research. This article, part of a two-part series by Diana, focuses on three tips for using PARES, the digital platform of the Archive of the Indies in Spain.

In the first part of this archive chronicle, “”An experiential approach to the Archive of the Indies”, I discussed why PARES is the AGI’s front façade for virtually every researcher nowadays. Even though PARES is an online tool, my user experience changed significantly once I was in the reading room. After months of searching for references and organizing them, I thought I had mastered PARES through Scott Cave’s helpful guide. But I was humbled during the first week at the archive when it became obvious that PARES does not reflect the entire holdings or archival organization of the AGI. This is certainly true for any archive or collection. Still, I did learn a few tricks along the way that changed how I approached the archive and its online catalog. This piece has three how-to’s in PARES to help make the research experience easier for researchers.

1) How to explore the AGI’s numerous subsections or how to use PARES like a print catalog

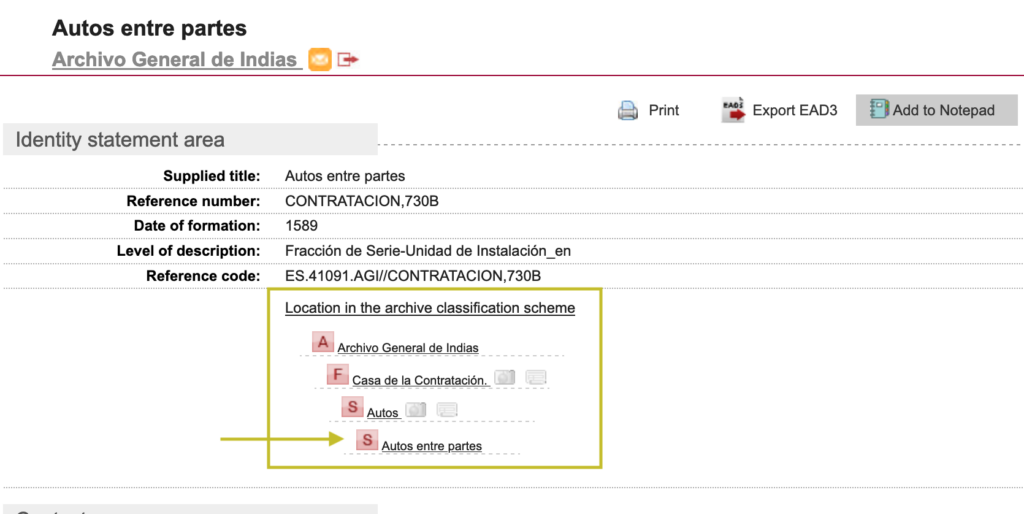

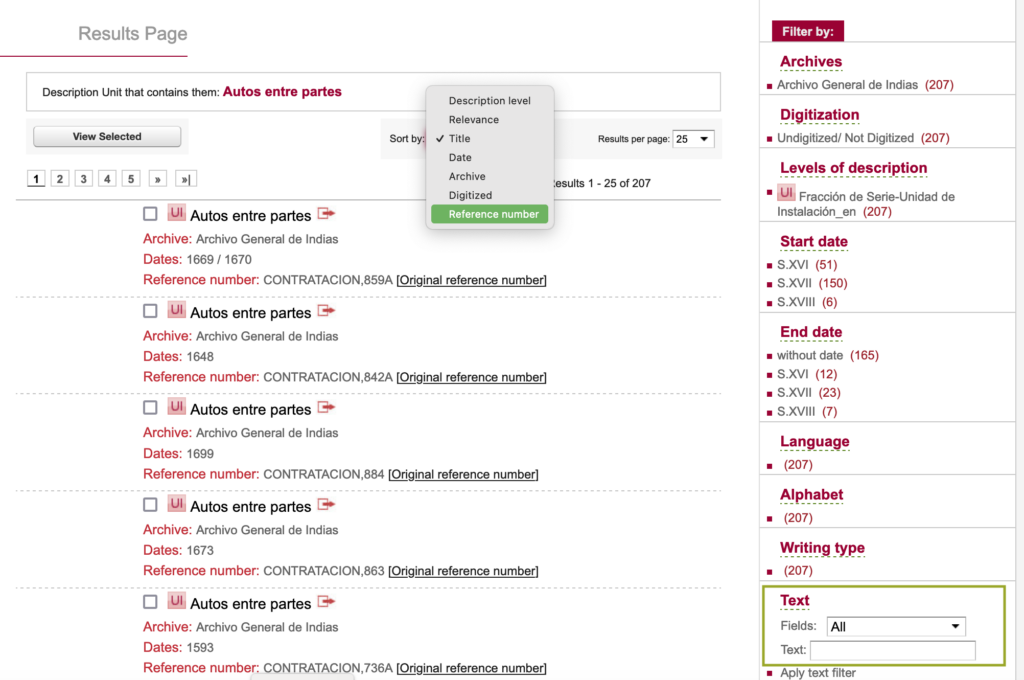

Most of the search results I initially got from PARES were located in the section of Contratación. However, this is the archive’s largest section with close to six thousand legajos and fifty-one sections. When I finally started consulting some of these references, I wondered why most of them came from “Autos entre partes” (litigation between private parties). Did this mean that this subsection was described in greater detail than others? What else was out there in this immense section?

Two PARES features make it easier to answer these questions:

Clicking on “Location in the Archive Classification Scheme” shows where a document or section is located within the archive.

If we click on any of the hierarchical locations, it will open a new tab or window where we can see how many units a section has and a broad description of its contents.

In this case, the subsection of “Autos entre Partes” has 207 legajos, but the Content and Structure section does not provide a substantial description. For many other archival sections, there might be a finding aid on the index file that lists references to print catalogs which you can consult at the AGI’s reading room. Identifying these broader archival sections along with the legajo range they cover is quite handy when consulting microfilmed portions of the AGI. While now considered an almost defunct technology, it is important to remember that several libraries across the Americas have AGI microfilms such as the Benson Latin American Collection, the Bancroft Library, or the Eusebio Dávalos Library at Mexico’s National Anthropology Museum.

Once we click on “207 units more”, I recommend sorting the Description Unit by Reference number. This places the oldest legajo on top of the list and allows you to systematically review the section. I also like to use the “text filter” to make targeted searches within a single description unit.

2) How to find digitized files that do not look like they have been digitized

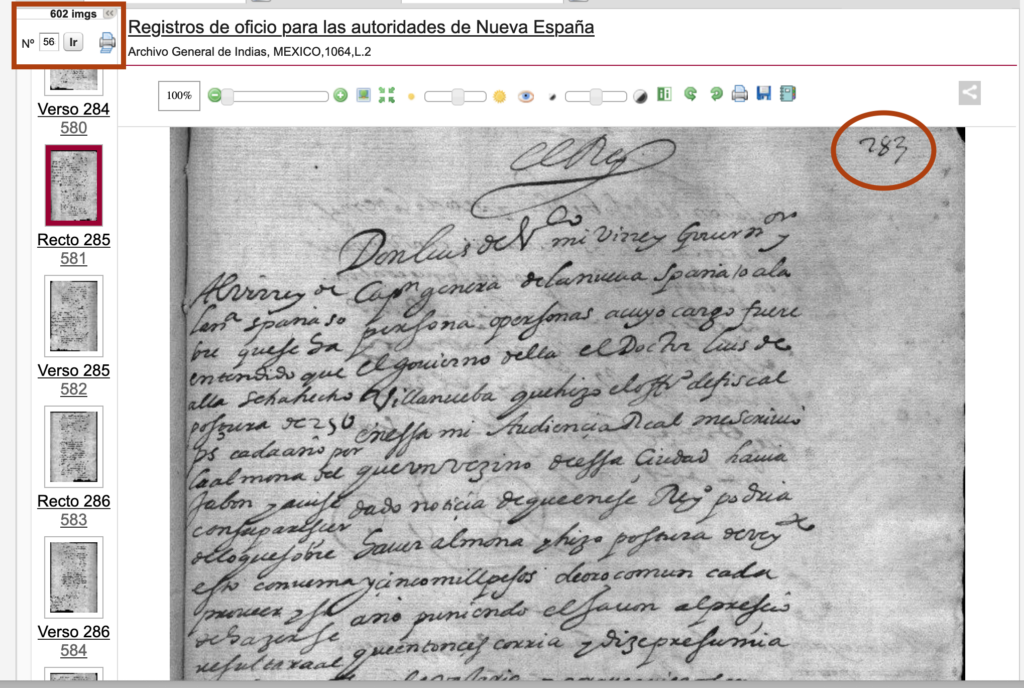

One of the best tips an AGI archivist shared with me was how to find apparently non-digitized documents from bound volumes known as libros. For example a reference with a geographical marker (e.g. Lima, Guatemala, Charcas, Indiferente) and an L such as MEXICO,1064,L.2,f.283r-283v indicates it comes from libros on the Gobierno section (including Indiferente). While the description and digitization of these books is almost complete, they are not always subdivided by individual files in PARES.

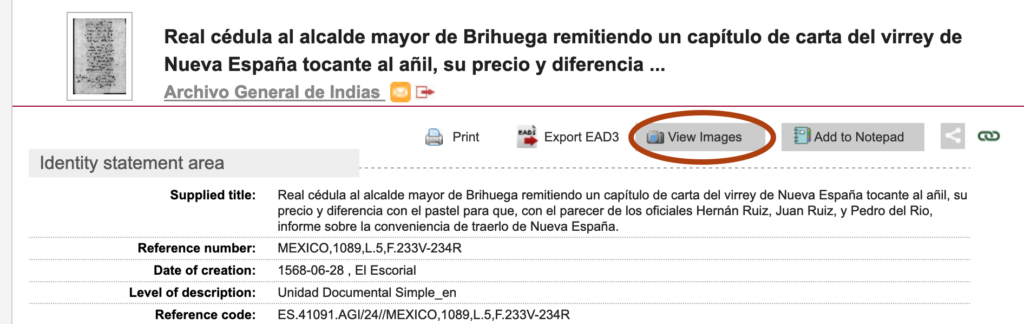

Here’s an example of a book that is clearly subdivided and can be easily accessed by clicking on “View Images”.

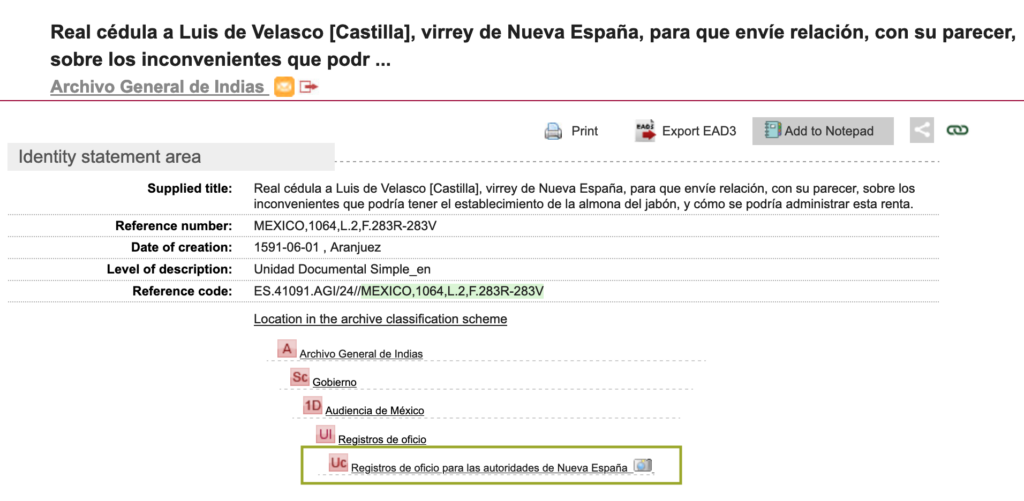

The reference below, however, looks like it has not been digitized because it does not have the camera icon. But since it has an “L”, we can almost be sure it has been digitized. Expanding the “Location in the Archive Classification Scheme”, shows that its containing section has a fully colored camera icon (when a camera is gray, it means the section has been partially digitized).

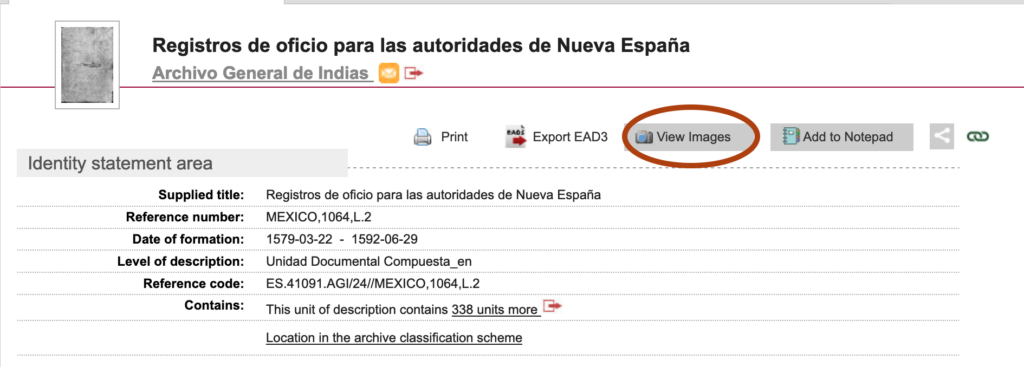

Once we click on this location, it will open a new tab where we can access the fully digitized libro.

Now it is only a matter of clicking on “view images” and finding the folios from the original reference. Since the PARES viewer operates by image number, this means we have to multiply the folio number by two if it’s a verso folio and subtract 1 if it’s a recto folio. Our reference number (283r-283v) suggests the image number should be 565.

Sometimes this might not work precisely so you might need to skim through a few pages to find the specific page numbers.

3) How to start identifying relevant documents for your research

Compared to its earlier version, PARES 2.0 has two new tools that are a good starting point to explore a new topic: the Authorities Search and MetaPARES.

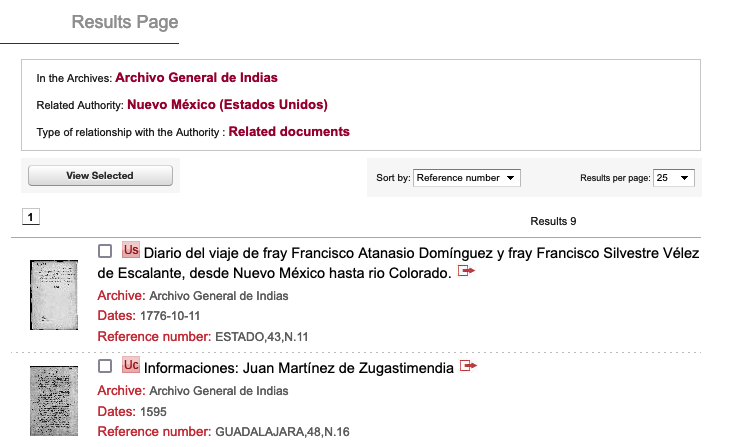

The Authorities Search works similarly to a subject search in a library catalog. The main difference is that the results will lead you to a virtual index file that lists at the end a list of the Spanish Archives where you can find your topic and the number of documents previously identified by archivists. This search is by no means comprehensive, but it is a good starting point. For instance, to know more about the bison found in New Mexico, an authorities search would be useful to identify the jurisdiction and place names used for this region during colonial times.

Screenshot of the AGI documents associated with the subject of New Mexico

Another tool that connects published and unpublished academic work to the holdings of the Spanish State Archives is MetaPARES. The goal of this portal is to refer researchers to secondary literature that cites Spanish Archives. The tool is still in development, but it is a good way to quickly become acquainted with Spanish scholarship and document collections.

The MetaPARES search for New Mexico lists four results. They are not many, but they are more targeted than your typical Google Scholar search and will likely be in Spanish.

It also goes without saying that learning Spanish paleography and early modern Spanish vocabulary is key to identifying relevant documents. There are many online tools and software such as the Dominican Studies Institute Paleography Tool, the Diccionario de Abreviaturas Novohispanas, or Transkribus that make this endeavor easier nowadays. Additionally, reading transcribed document collections and getting acquainted with the structure of Spanish bureaucratic documents will improve your own reading and comprehension of the materials you collect. Navigating the archives and documents of Colonial Latin America demands practice and patience, but this experience can be slowly built throughout the years and from afar. For me, it took about seven years, but it was worth the wait.

Diana Heredia-López is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of History at the University of Texas at Austin. Originally trained as a biologist in Mexico, she has specialized in the history of science and colonialism since 2012. Her current research examines dye cultivation and commerce as a framework to investigate early modern Hispanic extractivism, knowledge production, and material culture.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.