By Nakia Parker

Elizabeth L. Ring was a prominent public servant and social reformer in early twentieth-century Texas. During her marriage to Henry Franklin Ring, an attorney, Elizabeth became involved in campaigning for state funding for libraries, advocating for more educational and political opportunities for women, and spearheading efforts to enact laws that protected the rights of working women and children (such as minimum wage legislation). Yet, Ring left her most indelible mark on the prison reform movement in her home state. She tirelessly worked to better conditions in Texas prisons during the Progressive Era, and the Texas Committee on Prisons and Prison Labor formed under her watch. A document found among her papers at the Briscoe Center for American History shows us something about how a progressive activists thought about prison reform at that time. This is a questionnaire from the Psychology Department of Western State Penitentiary in Pennsylvania for the wives of incoming prisoners that was related to her research on prison conditions.

Western State Pen Questionnaire

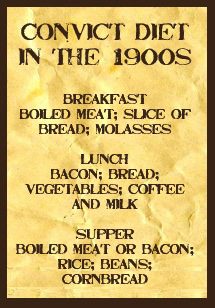

The questionnaire probes every crevice of a prisoner’s marital and familial relationships, posing questions on the state of the marriage before the husband’s incarceration, his work, personal and religious habits, his family history (including reputation in the community and the past criminal acts of siblings), as well as determining the extent of the wife’s personal knowledge of her husband’s crime. Even the wife’s activities are put under a microscopic lens, as evidenced by the questions “How are the children supported now? If you support them, how do you do it?” Indeed, to call the application intrusive seems a gross understatement. Yet, by examining the document in the context of American prison reform in the Progressive Era, the purpose of the questioning can be understood. In particular, prisons in the northern part of the United States, such as Western Penitentiary, experimented with programs that focused on the “reforming” of criminals through the use of individualized educational, medical, and psychiatric treatment. Thus, it appears that the prison psychology department utilized this invasive line of questioning in an attempt to explain motivations or reasons behind criminal behavior by conducting a thorough investigation of the prisoner’s background.

It is harder to ascertain how Elizabeth Ring used this particular questionnaire for her research. Was there something unique about the treatment programs of this prison that led Ring to believe this form could prove useful in pushing for penal reform in Texas? In addition, the reader has no way of knowing whether this paper served as the standard application for the wives of the incarcerated. Were there separate questionnaires for whites and non-whites? Or for native-born individuals and immigrants? More research would be necessary to answer these questions, but anyone interested in the Progressive Era, reform movements, prison history, or women’s history would doubtless find this an intriguing source.

You may also like in Texas History:

Confederados: The Texans of Brazil

“The Battle of Bandera Pass and the Making of Lone Star Legend”

A Texas Ranger and the Letter of the Law

“The Die is Cast”: Early Texans Face the Comanches

All images courtesy of the Texas State Library and Archives Commission’s exhibit ‘Fear, Force, and Leather: The Texas Prison’s System’s First Hundred Years, 1848-1948’

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.