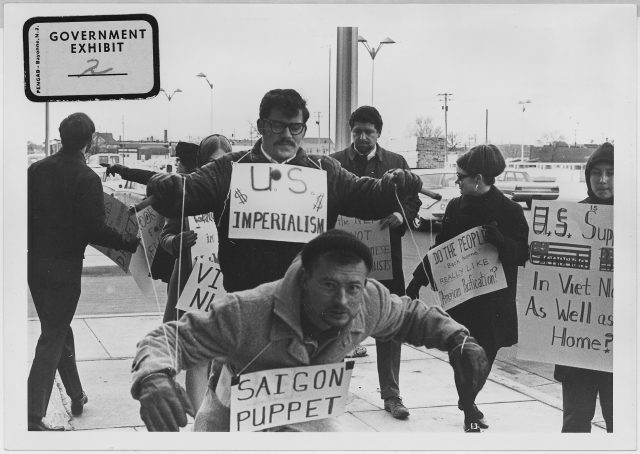

Why has the 50th anniversary of a year generated so much interest just now? The year was 1968, and it witnessed an extraordinary outburst of protest and upheaval – one that transcended international borders. While the protests were triggered by diverse events and conditions, they seemed linked by more general aims of combatting institutionalized injustice and government abuse. This panel will examine the specific background and dynamics of 1968 movements in France, Mexico, and the United States (including Austin, Texas). At the same time, it will ask why these movements surfaced at this particular juncture, across much of the globe.

Matthew Butler

Associate Professor of History

University of Texas at Austin

Judith G. Coffin

Associate Professor of History

University of Texas at Austin

Laurie B. Green

Associate Professor of History

University of Texas at Austin

Leonard N. Moore

Vice President of the Division of Diversity and Community Engagement (Interim)

George Littlefield Professor of American History

University of Texas at Austin

Jeremi Suri, moderator

Mack Brown Distinguished Chair for Leadership in Global Affairs

University of Texas at Austin

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.