By Peter Worger

Tucked into the pages of Nikolai Punin’s diary is a sliver of silver paper made into the shape of a fish. Its scales have been drawn with what appears to be black marker or charcoal in an Impressionist style on one side and in a Cubist style on the other. The fish has two fins along its underside and a pointed tail, most of which have brightly-colored orange tips, and there is a razor-like saw of a fin on its backside. An orange piece of yarn is tied to its mouth as if the fish had been caught with it, making it easy to hang or pull out of a book. The whole object is about the length of a page and, since it was found in a book, one can assume it was made to be used as a bookmark.

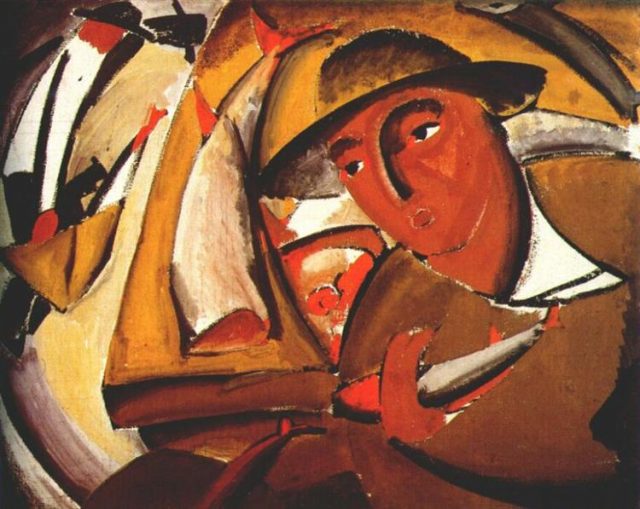

The fish was a gift from the famous Soviet avant-garde artist, Vladimir Tatlin, to his friend, the art historian Nikolai Punin. The two men worked together at The Museum of Painterly Culture in Petrograd in the early 1920s just after the Russian Revolution when the diary was written. Punin worked in the Department of General Ideology and Tatlin was producing an experimental play by the poet Velimer Khlebnikov, another friend and collaborator in the circle of Russian revolutionary, avant-garde artists. For Punin, Tatlin represented a particular quality of Russian art that made it surpass the latest Cubist innovations in painting coming from France. In 1921, Punin had already written a polemic entitled, “Tatlin (Against Cubism).” In this short work, he argued that Tatlin made the same innovations in art as the French Cubists, but surpassed them because the tradition of icon painting in Russia gave the Russian avant-garde a particular appreciation of the paint surface. The lack of a Renaissance tradition of perspectivalism, according to Punin, also gave the Russian avant-garde a much freer relationship to space. Punin referred to The Fishmonger, as one of three paintings that represented Tatlin’s start in this direction. In that painting we can see multiple fish that have the silver and orange coloring as the paper fish found in Punin’s diary. Tatlin’s early experiences with church art, painting icons, and copying wall frescoes, was crucial in the development of his style as well as his ideas about the role of art in revolutionary society. The icon was both a work of art and an object for everyday use. This emphasis on the image as everyday object became important in expanding Tatlin’s creative pursuits to include the construction of utilitarian objects to transform the nature of everyday life in the USSR during the transition to socialism.

The Fishmonger, by Vladimir Tatlin, 1911 (via Wikiart).

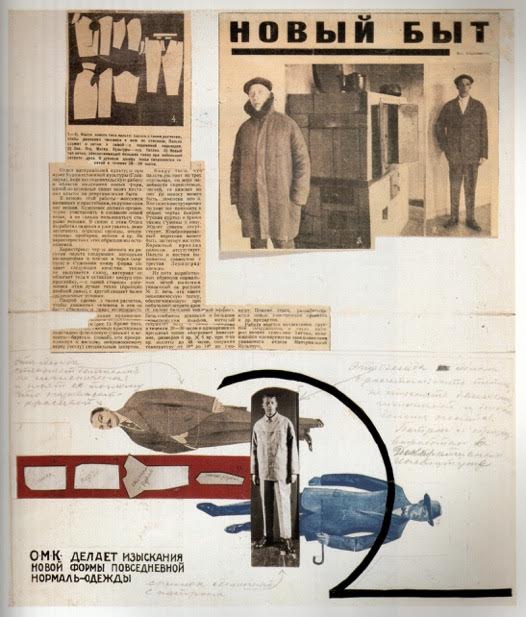

In 1923, Tatlin became the Director of the Section for Material Culture at the Museum of Painterly Culture. During his tenure there, he authored several documents outlining his general program for the role of material culture in the USSR. In an article written under his direction called “The New Way of Life,” he described a series of new projects and prototypes, namely a new design for a coat, and one of five new designs for an oven that could cook and keep food warm for 28 to 30 hours and also keep the home heated economically. Tatlin incorporated the text of “The New Way of Life” into a controversial work of the same name, a photo-montage showing images of the designs that were meant to depict that revolutionary new way of life. He created it for display in the showroom of the Section for Material Culture and the designs were also shown at the Exhibition of Petrograd Artists of All Tendencies. Punin wrote a favorable review of Tatlin’s work in the exhibition, but other critics who believed that art should occupy a place “beyond the realm of the everyday” found the designs inappropriate. Tatlin’s work was revolutionary in that it challenged this traditional boundary between art and the everyday.

The fish is an important indication of a close personal and professional relationship between the artist, Vladimir Tatlin, and his admiring critic, Nikolai Punin, and it represents the ways that Tatlin and Punin tried to outline a new revolutionary program for art. It also is an example of that very revolutionary impulse in that it is an object to be contemplated for its aesthetic beauty and also to be used for a utilitarian purpose as a bookmark. Tatlin’s work paved the way for a new interpretation of art as something that could be figurative as well as useful; art in revolutionary society could have a place in the daily lives of every individual and not only in the lofty realm of the art establishment. This little fish offers a window onto the theories of the period of the Russian Revolution, when people sought to rethink the entire Western European model of not only aesthetics but also society.

![]()

Anonymous, “New Way of Life,” in Tatlin, ed. Larissa Alekseevna Zhadova (1988).

John E. Bowlt, review of O Tatline, by Nikolai Punin, I. N. Punina, V. I. Rakitin, Slavic Review 55, no. 3 (1996).

Christina Kiaer, “Looking at Tatlin’s Stove,” in Picturing Russia: Explorations in Visual Culture, Valerie A. Kivelson and Joan Neuberger, eds (2008).

Jennifer Greene Krupala, review of O Tatline by N. Punin, I. N. Punina, V. I. Rakitin, The Slavic and East European Journal 40, no. 3 (1996).

John Milner, Vladimir Tatlin and the Russian Avant-Garde (1983).

Nikolai Punin, “Tatlin (Against Cubism),” in Tatlin, ed. Larissa Alekseevna Zhadova (1988).

Rebecca Johnston studies a letter pleading for Nikolai Punin’s release from prison in Policing Art in Early Soviet Russia.

Andrew Straw looks at the evolution of Soviet communism in Debating Bolshevism.

Michel Lee discusses the relationship between Leninism and cultural repression in Louis Althusser on Interpellation, and the Ideological State Apparatus.

![]()