On June 8, 2010 an Egyptian Google executive based in Dubai, named Wael Ghonim, was stunned by a YouTube video that featured a fellow citizen by the name of Khaled Said, bloodied and disfigured. It turned out that the Egyptian police had beaten Said to death and mutilated his body. Appalled by this short video that ran viral through Arab social media, Wael Ghonim created a Facebook page that came to symbolize the involvement of ordinary people in creating change. “We are all Khaled Said” was the name of the Facebook page, adding the motto “today they killed Khaled, and if I don’t act for his sake, tomorrow they’ll kill me.” This internet-based movement contributed to fomenting the uprising in Egypt that ultimately overthrew the corrupt, 30-year regime of Hosni Mubarak. Throughout modern Egyptian history, the media and popular culture have played a crucial role in shaping and informing major political events, as Ziad Fahmy makes evident in Ordinary Egyptians: Creating the Modern Nation Through Popular Culture.

Fahmy argues that the illiterate and lower classes played an important role in forging Egyptian nationalism. Drawing on otherwise unconsulted sources in colloquial Egyptian, such as songs, popular poems, vaudeville plays, and other sources in the spoken and vernacular Cairene dialect, Fahmy shows that popular culture was instrumental in helping to create a new national identity. Fahmy’s study of these sources fills a sizable gap in the historiography of Egyptian nationalism by lending a voice to the majority of the population. While previous research on Egyptian nationalism was built on intellectual history (Gershoni, Rethinking Nationalism and Smith The Ethnic Origins of Nations), Fahmy’s Ordinary Egyptians turned the approach to Egyptian nationalism from elites to non-elites.

Fahmy argues that the illiterate and lower classes played an important role in forging Egyptian nationalism. Drawing on otherwise unconsulted sources in colloquial Egyptian, such as songs, popular poems, vaudeville plays, and other sources in the spoken and vernacular Cairene dialect, Fahmy shows that popular culture was instrumental in helping to create a new national identity. Fahmy’s study of these sources fills a sizable gap in the historiography of Egyptian nationalism by lending a voice to the majority of the population. While previous research on Egyptian nationalism was built on intellectual history (Gershoni, Rethinking Nationalism and Smith The Ethnic Origins of Nations), Fahmy’s Ordinary Egyptians turned the approach to Egyptian nationalism from elites to non-elites.

The primary problem that Fahmy raises relates to many third world societies. How can we investigate nationalism in societies with more than 90 percent illiteracy? Focusing on Egypt in the last quarter of nineteenth century and the beginning of twentieth, when no more than 6.8% of the population was literate, Fahmy unequivocally discards Eurocentric theories as counterproductive when applied to illiterate societies. Thus he supplements the study of print capitalism by a more inclusive media capitalism, which is better able to account for unnoticed or undocumented cultural occurrences. “Cultural products,” writes Fahmy in the preface, “are not socially relevant unless they are communally and socially activated.” In other words, Fahmy is concerned with the ways individuals and communities communicate with and digest cultural information. Print capitalism was a luxury in late-nineteenth century Egypt. The illiterate population, who couldn’t relate to a written newspaper, still actively participated in creating national identity through the new mass media and entertainment industry. Earlier theories of nationalism that dismissed “orality and direct social interactions” ignored not only the experiences of the vast majority of the population, but more importantly, as as Fahmy notes, paraphrasing Mikhail Bakhtin,they ignored the “social life of discourse outside the artist’s study, discourse in the open spaces of public squares, streets, cities and villages.”

Fahmy stresses the centrality of Cairo and to a lesser extent Alexandria as hubs of cultural activity that radiated and distributed the popular Cairene dialect throughout Egypt. Thanks to the new industrial infrastructure (railroads, telegraph, and post office), the urban areas and the countryside became more connected. New musical and comedic theater troupes could reach more isolated populations. Editors of popular journals, Ya’qub Sannu’, ‘Uthman Jalal, and ‘Abdellah Nadim, defiantly used the colloquial Egyptian language, jokes, azgal (colloquial poetry), and cartoons as a counterhegemonic tools to include the masses in the nascent Egyptian identity.

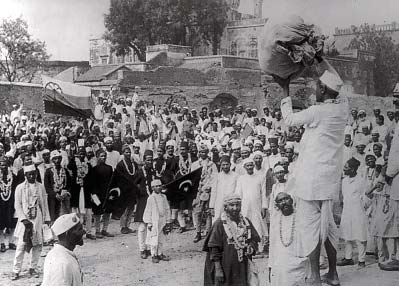

The second half of Ordinary Egyptians shows popular national identity developing political significance. The more the British colonial authorities (and the elite who were complicit with them) attempted to staunch the press and forcefully impose the press law, the more popular illicit publications became. The masses that took to the streets in the spring 1919 revolution provided undeniable evidence of popular culture’s effectiveness.

Not every popular act, song, or poem, however, should be construed as counterhegemonic or helping in creating the new nation. In Ordinary Egyptians, Fahmy leaves no space for what Rogers Brubaker coined, “National Indifference”. For Brubaker people can be mostly indifferent about their identity and ethnicity. Certainly, people sing national songs, but they also sing and recite poems out of pleasure in the first place, rather than to express sympathy for the nation or animosity toward the British.

Fahmy succeeds remarkably well in discrediting the top-down understanding of cultural diffusion, though he over estimates the role of the capital cities, Cairo and Alexandria, in originating and disseminating culture. His strong point, however, is the discussion of the role of popular culture in Egyptian nationalism. Thus, the contemporary uprisings in Egypt that ousted Housni Mubarak can be seen as a current reincarnation of previous revolutions that were driven, at least in part, by public mass media and popular culture.

You may also like:

Yoav di-Capua’s FEATURE piece on his recent book, Gatekeepers of the Arab Past.

Yoav di-Capua’s blog post about political and social conditions in Egypt eight months after Mubarak’s ouster in February 2011.

Lior Sternfeld’s review of Erez Manela’s The Wilsonian Moment.

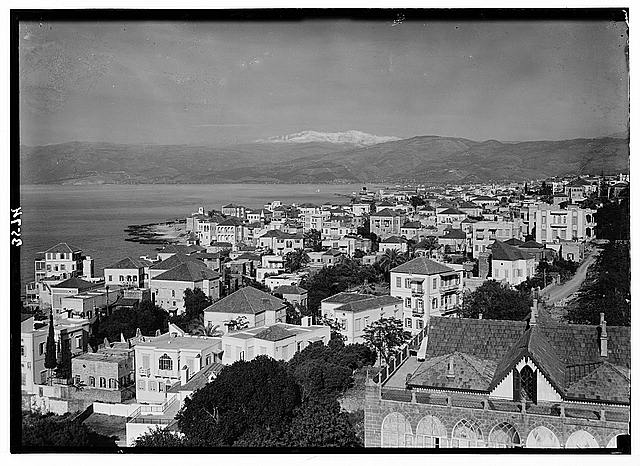

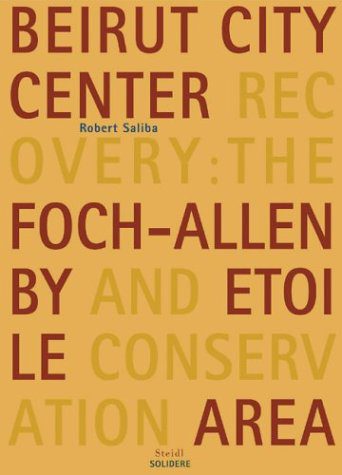

News programs the world over broadcast it into the homes of millions of people from 1975 till the Lebanese Parliament ratified the Taif accord in late 1989. Less well known is the reconstruction process that began in the Lebanese capital almost immediately after the war ended and which continues today. After commissioning but failing to implement an initial plan in 1992, the Lebanese government entrusted the reconstruction to Société libanaise pour le développement et la reconstruction de Beyrouth (Solidere), which was founded by then-Prime Minister Rafic Hariri, in 1994. Focusing primarily on the downtown area, the company sought to preserve what few buildings remained, create an international business district, and make a profit. As is the case with many urban reconstruction projects, Solidere’s plan was met with resistance and protest, especially considering the still-divided nature of Lebanese society. Therefore, Solidere took on the secondary task of defining and emphasizing an architectural heritage that could bridge the sectarian gaps inherent to Lebanon and thus Beirut.

News programs the world over broadcast it into the homes of millions of people from 1975 till the Lebanese Parliament ratified the Taif accord in late 1989. Less well known is the reconstruction process that began in the Lebanese capital almost immediately after the war ended and which continues today. After commissioning but failing to implement an initial plan in 1992, the Lebanese government entrusted the reconstruction to Société libanaise pour le développement et la reconstruction de Beyrouth (Solidere), which was founded by then-Prime Minister Rafic Hariri, in 1994. Focusing primarily on the downtown area, the company sought to preserve what few buildings remained, create an international business district, and make a profit. As is the case with many urban reconstruction projects, Solidere’s plan was met with resistance and protest, especially considering the still-divided nature of Lebanese society. Therefore, Solidere took on the secondary task of defining and emphasizing an architectural heritage that could bridge the sectarian gaps inherent to Lebanon and thus Beirut.