By David Rahimi

Writing in the middle of World War II, Freya Stark, a well-known British explorer and Arabist working for the Ministry of Information in the Middle East, penned an unpublished – and ultimately unfinished – twenty-five page essay, which she entitled Apology for Propaganda. When we think of government propaganda, we typically think of faceless bureaucrats churning out sensationalized banners, radio broadcasts, and reports about victories, the enemies’ lies, and various kinds of disinformation. Stark’s Apology, however, provides a unique glimpse into how propagandists justified and viewed their own work in a critically self-conscious manner. On a larger scale, the manuscript reflects on an intimate level the dynamics of British colonial thought, particularly a steadfast belief in the nobility of Britain’s colonial “civilizing mission.” Stark’s Apology not only reflects an available theory of propaganda discussed within the Ministry of Information, but also the persistent belief that, despite any shortcomings, imperialism was really benevolent for Arab colonial subjects.

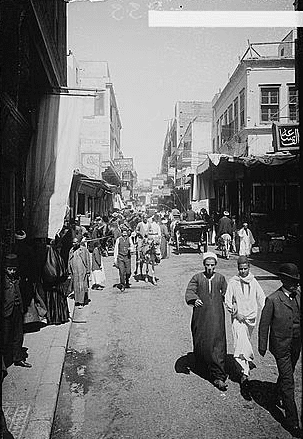

Freya Stark (via Alchetron).

By her thirties, Freya Stark (1893-1993), an impulsive British explorer of the Near East, developed a romanticized and idealistic obsession with the Arab world and Persia in the same vein as T.E. Lawrence, whom she much admired. She traveled among the Druze, explored Luristan and the hideout of the fabled Assassins at Alamut, and wrote extensively about her travels in Baghdad, Yemen, Arabia, and other parts of the Middle East. When WWII began, Stark volunteered to serve in the British war effort and she was assigned to the Ministry of Information where her linguistic and literary talents were well-suited.

Stark likely wrote this piece sometime between October 1943 and May 1944, while traveling in America on an official diplomatic tour to clarify the British position on the Zionist question. Ultimately, it seems the decision was made not to publish the Apology because Stark’s boss, Stewart Perowne, thought it was too revealing about British intelligence efforts in Egypt and Iraq in the still ongoing war.

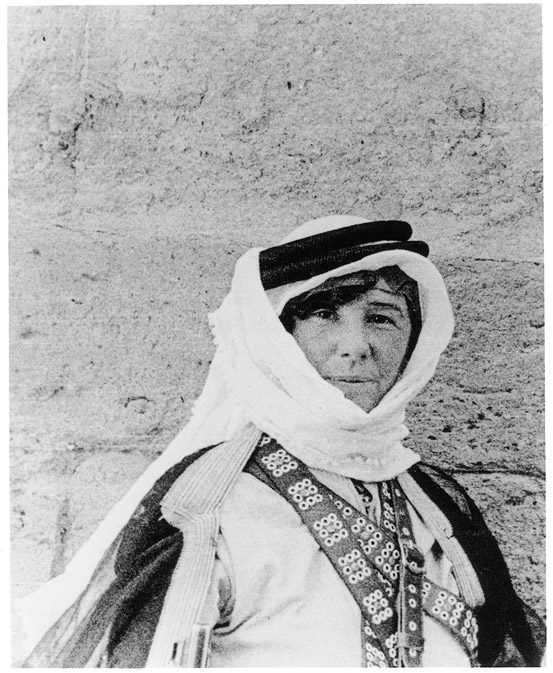

British WWII propaganda after Mussolini’s unsuccessful invasion of Egypt in 1942. The poster depicts captured Italian troops entering Cairo under British guard (via Wikimedia Commons).

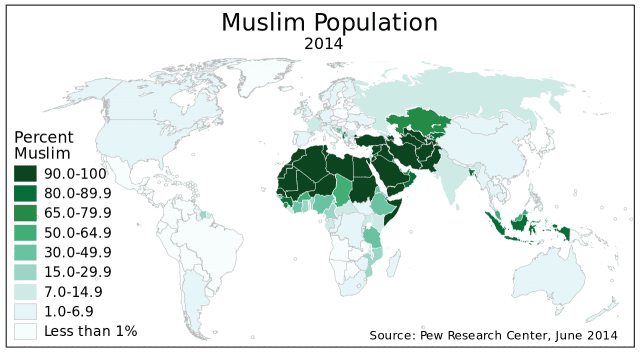

Stark begins the essay by arguing that propaganda fundamentally deals with the “originating and spreading of ideas.” However, propaganda has two distinct meanings: (1) the propagation of a “gospel” or firmly held set of beliefs, and (2) deceitful information. Both grew out of the Jesuit tradition, with the former being an innocent form of “persuasion,” while the latter took form as people associated the Jesuits with “unscrupulous subtlety.” Persuasion meant simply to truthfully present one’s beliefs in a dialogue (“two-way traffic”) with the target audience, making use of slogans and positive statements. Stark firmly believed the government should wholeheartedly embrace this kind of propaganda, since ideas “are as potent as drugs.” Indeed, there is a “duty” to firmly explain the British and Allied cause when they feel confident of the justice and necessity to prevent others from heading over a “precipice.” For Stark, this was connected to her firm belief that the “British desire to encourage freedom in the Arab world is perfectly sincere.” Justifiable propaganda could only be that which worked for the good of the audience, in this case the Arabs. On the other hand, Stark thought that bribing and trickery were repugnant as well as ineffective means of persuasion, and cooperation with Arabs was necessary, since the most persuasive formulations of secular democratic ideals could only be expressed in Arabic by other Arabs and not through translation.

Stark then moved from these ideas to show how she tried to implement them in her Ikhwan al-Hurriya (Brotherhood of Freedom), an anti-fascist group in Egypt and Iraq. Based on the organizational examples set by the Bolsheviks and Muslim Brotherhood, this project consisted of a diffused network of loose cells, where British and Arab members could discuss the democratic principles that they shared. She writes that, despite some initial difficulties, the British-inspired Brotherhood garnered about 40,000 members throughout the Middle East at its peak. The British authorities were highly appreciative of this effort, though despite Stark’s high hopes, the organization was officially outlawed in Egypt in 1952.

A chief reason for this was the contradiction within the Brotherhood about politics. Stark envisioned it as an apolitical group and so had to turn several “good men” away in Iraq because of their interest in politics. However, an organization that was ostensibly meant to promote democratic principles could not help but be political in a colonial environment. Stark was happy that there were young Arab men who were receptive to the British message, but she seemed to think that this could be conducted on British terms without raising political questions about Britain’s decidedly undemocratic role. Stark easily mistakes the friendships she formed and admiration for democratic ideas she found with an overall positive disposition to British colonialism. Furthermore, there is no mention of the popularity of Muslim Brotherhood’s anti-British efforts or how Ambassador Miles Lampson’s use of tanks on February 4, 1942 to compel King Farouk to accept the Egyptian nationalist Wafd Party into the government led to the discrediting of the king, the Wafd, and parliamentary democracy as mere British tools. The enormous popularity of Gamal Abdel Nasser’s nationalist and authoritarian government beginning in the 1950s also belies Stark’s overly enthusiastic tone in the manuscript. Unlike T.E. Lawrence, who had seen Britain renege on its promises at Versailles after WWI, Stark believed wholeheartedly in the goodness of the British imperial project and whatever did not fit in with this image she discounted as an aberration or simple mistake.

Nasser and the Free Officers overthrew the Egyptian monarchy in 1952, marking the decline of British influence in Egypt (via Wikimedia Commons).

Stark’s unpublished Apology shows us how some British propagandists in the Middle East theater of WWII conceived of their roles as good-natured persuaders. They were not oblivious to accusations of cynical propaganda and Stark’s essay shows a conscious effort to articulate a morally acceptable form of propaganda that could serve British and Arab interests, in that order. Stark reflects a strain of British colonial thought that, while sympathetic to Arabs, still thought that British dominance was a guiding hand that benevolently, yet condescendingly, treated colonial subjects as paternalistic clients.

![]()

Freya Stark’s “Apology for Propaganda,” can be found in handwritten and typescript drafts, Container 1.3. Freya Stark Collection 1893-1993 (bulk 1920-1976). Harry Ransom Center, University of Texas-Austin.

Additional sources:

William Cleveland and Martin Bunton, A History of the Modern Middle East (2009)

Jane Fletcher Geniesse, Passionate Nomad: The Life of Freya Stark (1999).

Efraim Karsh and Rory Miller, “Freya Stark in America: Orientalism, Antisemitism and Political Propaganda,” Journal of Contemporary History 39, 3 (July, 2004): 315-332

Temple Wilcox, “Towards a Ministry of Information,” History 69, 227 (1984): 398-414

![]()

More by David Rahimi on Not Even Past:

Modern Islamic Thought in a Radical Age, by Muhammad Qasim Zaman (2012)

You may also like:

Emily Whalen recommends A Prince of Our Disorder: The Life of T.E. Lawrence, by John E. Mack (1976).

Ogechukwu Ezekwem reviews The Dual Mandate in British Tropical Africa, by Frederick John Dealtry Lugard (1965).

![]()

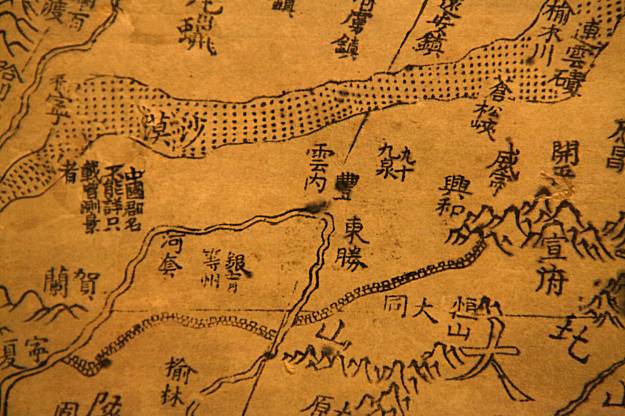

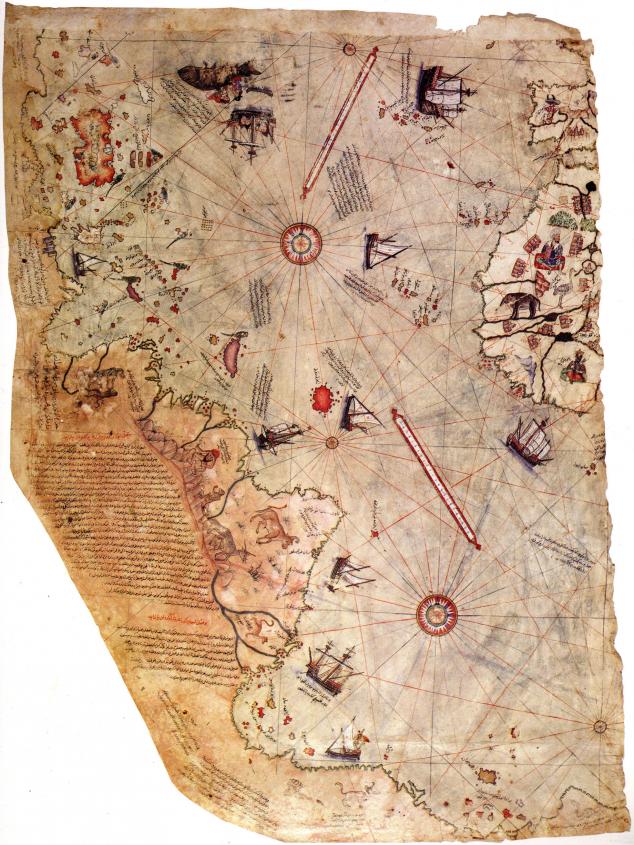

In The Ottoman Age of Exploration, Giancarlo Casale contests the prevailing narrative that characterizes the Ottoman Empire as a passive bystander in the sixteenth-century struggle for dominance of global trade. Using documents from archives in Istanbul and Portugal, Casale shifts our attention east and demonstrates that the Ottomans were actively engaged as rivals to the Portuguese for control of the lucrative spice trade and sea lanes of the Indian Ocean.

In The Ottoman Age of Exploration, Giancarlo Casale contests the prevailing narrative that characterizes the Ottoman Empire as a passive bystander in the sixteenth-century struggle for dominance of global trade. Using documents from archives in Istanbul and Portugal, Casale shifts our attention east and demonstrates that the Ottomans were actively engaged as rivals to the Portuguese for control of the lucrative spice trade and sea lanes of the Indian Ocean.

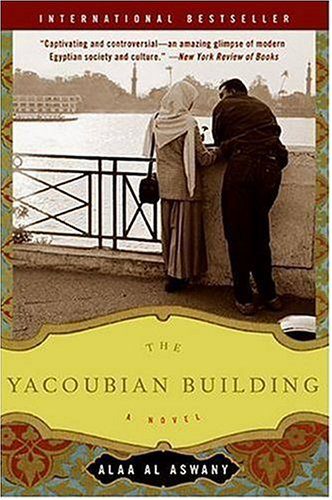

wealthy and corrupt businessman; and a lonely newspaper editor looking for lasting love, are each connected to the building, either because they rent office space there, or have an apartment there, or visit someone who lives there. A scathing indictment of governmental corruption and a critique of the class-based limitations of contemporary Egyptian society, Yacoubian Building is nevertheless a piquant and entertaining read.

wealthy and corrupt businessman; and a lonely newspaper editor looking for lasting love, are each connected to the building, either because they rent office space there, or have an apartment there, or visit someone who lives there. A scathing indictment of governmental corruption and a critique of the class-based limitations of contemporary Egyptian society, Yacoubian Building is nevertheless a piquant and entertaining read.