By Adam Clulow

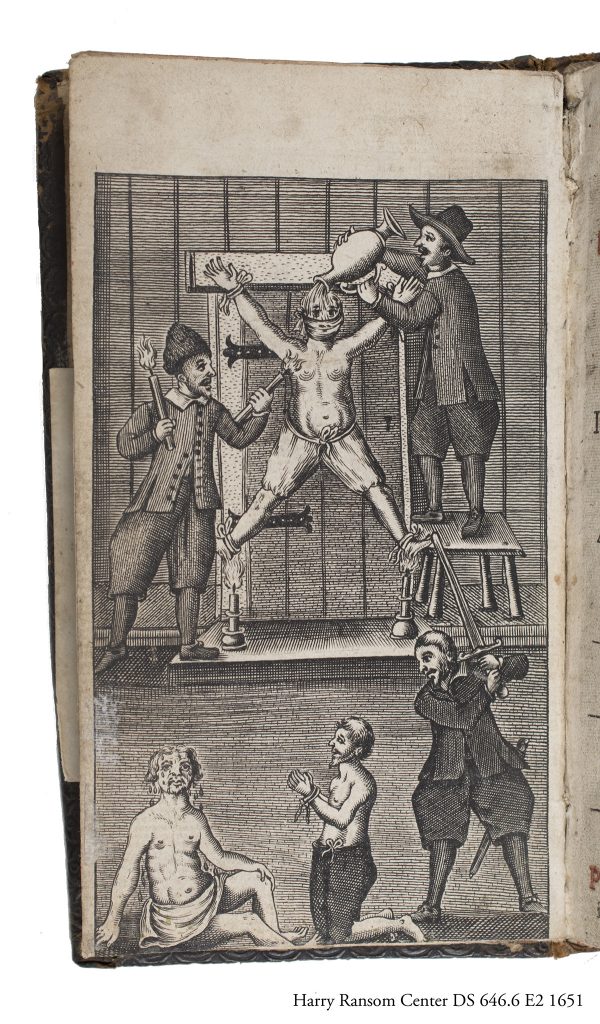

On February 23, 1623, a Japanese mercenary called Shichizō in the employ of the Dutch East India Company (Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie or VOC) was arrested for asking questions about the defenses of one of the company’s forts on the remote island of Amboina in modern day Indonesia. When he failed to provide an adequate explanation, he was waterboarded, a cloth “put before his face and fastened behind his head, hanging upon under his chinne, [and] after this the water was poured upon his head.” The result of this “torture of water,” or waterboarding as we would call it today, was a confession, that Shichizō had joined a plot orchestrated by a group of English merchants to seize control of the fortification and ultimately to rip the spice-rich island from the company’s grasp.

Armed with this information, the VOC governor proceeded to arrest, interrogate, and ultimately to torture the remaining ten Japanese mercenaries in the garrison, all of whom admitted to signing onto the plot in return for a substantial reward. A few days later, attention turned to the English, who also confessed, also under torture, to a role in a conspiracy aimed at the “taking of the castle, and the murdering of the Netherlanders.” On March 9, an improvised tribunal of VOC employees with the governor at their head convened to render judgment on the conspirators. The result was an emphatic guilty verdict and shortly thereafter ten English merchants and ten Japanese mercenaries were executed in the public square outside the fortress.

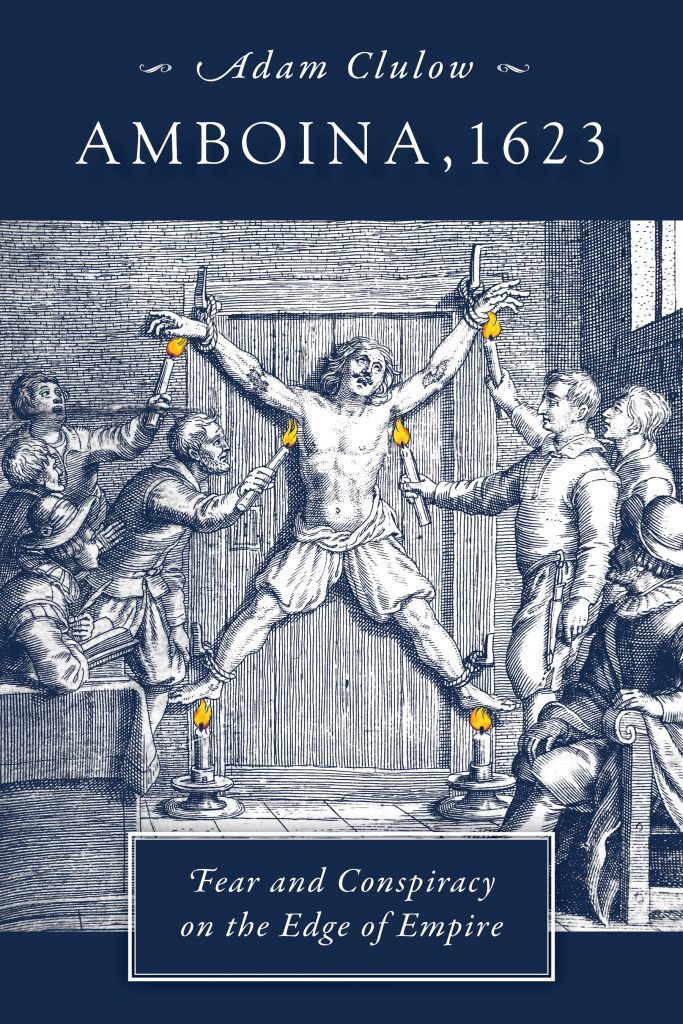

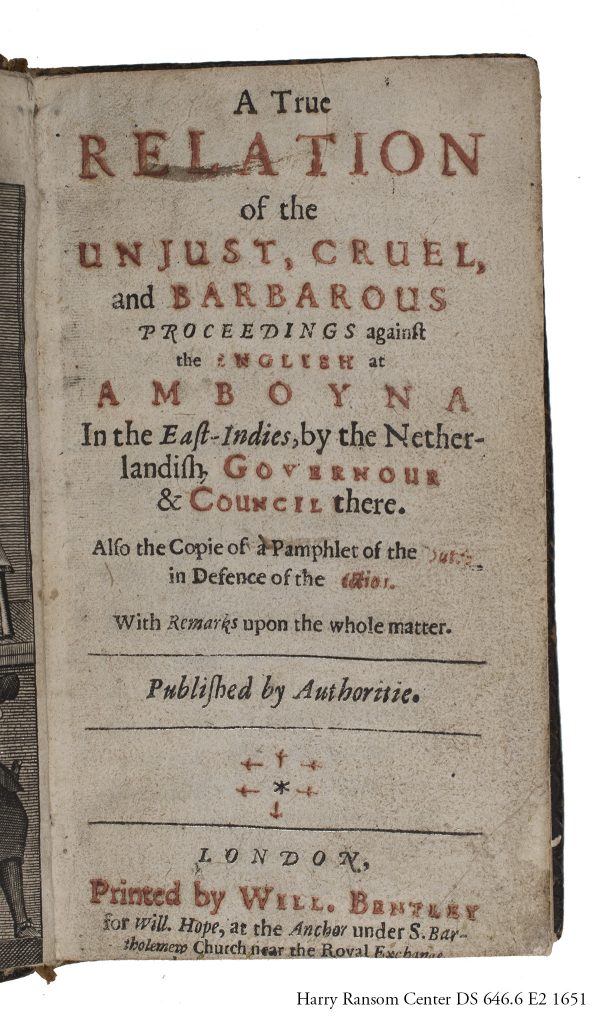

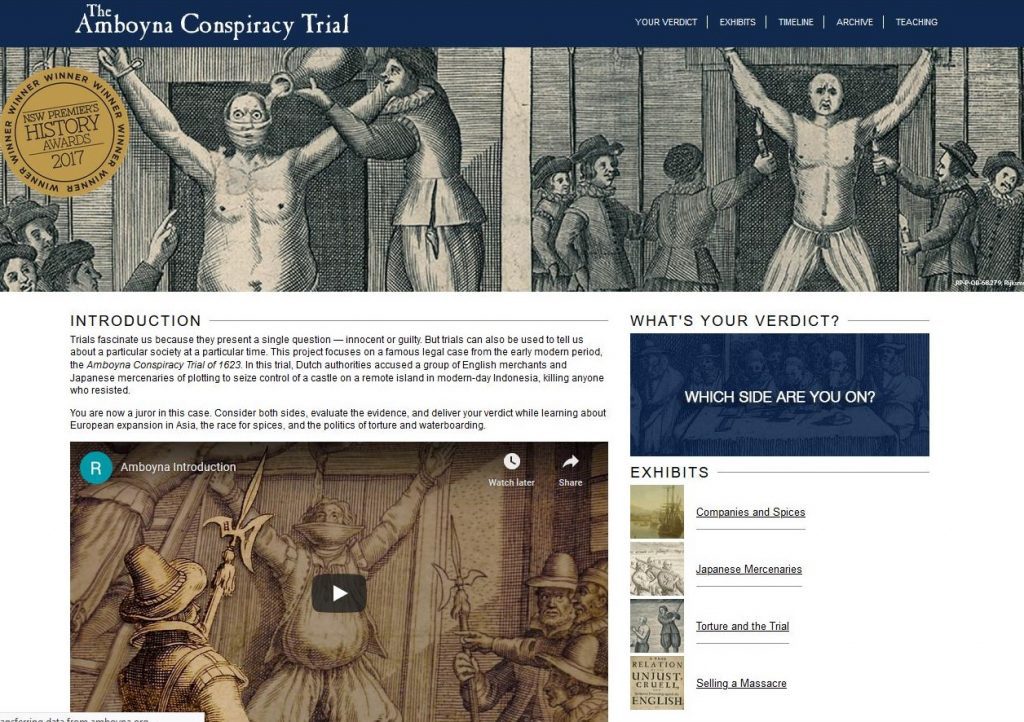

When news of what had happened on Amboina reached London at the end of May 1624, it sparked immediate outrage from the directors of the English East India Company, from the monarch, James I, and by all accounts from the general public. Passions were further inflamed by the publication of a slew of incendiary pamphlets on both sides that sought either to damn the Dutch as bloody tyrants or condemn the English as faithless traitors. All of these were accompanied by ubiquitous images of torture and execution at the hands of Dutch officials.

The result was that, despite occurring thousands of miles away in an unfamiliar part of the world, the trial on Amboina swiftly escalated to become one of the most famous legal cases of the age and the subject of a long-running dispute between the Dutch and English governments, which clashed bitterly over the twin issues of blame and compensation. It took close to a decade for the initial uproar to die down but the case remained prominent throughout the seventeenth century, generating a continuous flow of publications including pamphlets, sermons, broadsheet ballads and even a stage play penned by John Dryden in 1673. So famous was the case that its remnants are scattered in archives across the world including the Harry Ransom Center at UT Austin, which preserves a remarkable set of pamphlets related to Amboina.

Things did not end in the seventeenth century. The controversy was periodically resuscitated in subsequent centuries, reappearing, for example, in the Boer War (1899-1902) when it used by English writers to illustrate the essential villainy of not only the Dutch but also, more tenuously, their Afrikaner descendants in South Africa. It resurfaced even more recently in Giles Milton’s hugely popular history of these events, Nathaniel’s Nutmeg (1999), which repeated some of the standard charges made against the VOC.

For hundreds of years now, scholars and popular writers have fought over just what happened on Amboina in 1623. Across this long period, the debate has split along remarkably static national lines. For their part, English writers insist that no plot existed and hence that VOC actions on Amboina was nothing more than the judicial murder of innocents. In contrast, Dutch historians are clear that some sort of conspiracy existed, even if it was still inchoate, and hence that the legal proceedings were essentially justified.

My book was born from a sense of frustration with standard approaches to the case. It aims to move beyond the conventional debate over English guilt or innocence by looking instead at the territory where the trial took place and what was happening there in the weeks and months before Shichizō first appeared on the walls of the fort.

The book starts by shifting the spotlight away from the standard focus on the accused English conspirators to the three Asian parties, local polities on Amboina, Japanese mercenaries, and slaves primarily from South Asia, supposedly implicated in the plot. While the involvement of such different groups raises questions about the likelihood of such an expansive conspiracy, it also reveals something about how the Dutch East India Company was changing in this period. As it dove deeper and deeper into the region’s politics, the organization turned increasingly to Asian settlers to populate its colonies, Asian slaves to provide labor, and Asian fighters to wage war alongside its troops.

Exploring each of these groups in turn, Amboina, 1623 argues that while this process of what one scholar calls “Asiafication” allowed the Company to set down roots in the region, it also created a deep well of colonial anxiety. By working through each element of the supposed plot, the book sets out to trace how the questions of a single young Japanese soldier morphed into a sprawling conspiracy and how the case was driven forward by a potent combination of genuine crisis, imagined threat, and overpowering fear that propelled a rapid escalation from suspicion to torture and finally to mass execution.

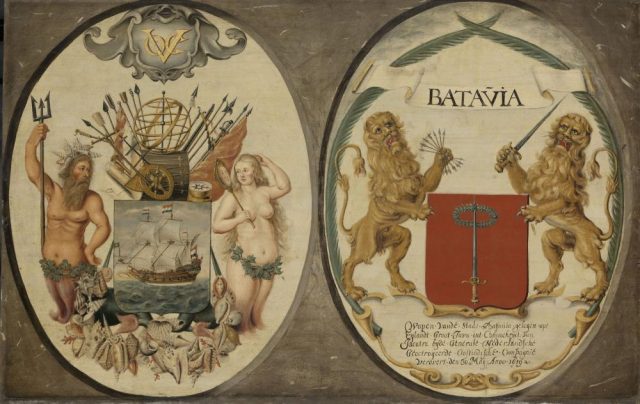

In 2006, then prime minister Jan Peter Balkenende called in an impromptu address to the Dutch House of Representatives for a revival of what he described as the “VOC mentality” (VOC- mentaliteit). What he meant, as far as we can make out, was a revived dynamism, optimism, and above all confidence that permitted the Dutch to dominate global commerce in the seventeenth century and which would enable the modern-day Netherlands to recover, in his view, some of its luster by harnessing this spirit. And we are all familiar with the images of Dutch confidence and success from the seventeenth century that are scattered across museums in the Netherlands and beyond.

Such depictions show a familiar image of the confident, conquering European standing in a transformed landscape surrounded by the technologies of power and looming over colonial subjects. In fact, and despite such representations, VOC officials and merchants lived in a world filled with terrors. As they moved into the region, Dutch agents were plunged into an alien landscape that was crowded with sophisticated societies, long-established political and economic networks, and powerful states capable of mustering vast military resources. Clinging to the coast, they felt acutely and constantly vulnerable. Recognizing the pervasive role of fear helps explain the frequently chaotic nature of the Amboina trial. It also tells us something about the Dutch empire in a period still commonly referred to as the Golden Age. Looking closely at the Amboina trial is a reminder that the “VOC mentality,” if we can use such a term, was dominated as much by fear as by confidence, and that this fear dictated how Company officials interacted with the world around them. It is, in other words, something to be studied and understood, certainly, but not emulated.

Adam Clulow, Amboina, 1623: Fear and Conspiracy on the Edge of Empire (2019)

Online Resources

In the process of writing the book, I developed an interactive website, The Amboyna Conspiracy Trial (www.amboyna.org), designed to take students into the heart of the Amboina trial. The site allows you to work through the details of the case guided by commentary from historians and barristers and come to a final verdict as to guilt or innocence.

Further Reading

Learn more about the Amboina conspiracy and related seventeenth-century imperial encounters:

Alison Games, Inventing the English Massacre: Amboyna in History and Memory (2020)

Brilliantly explores how the case entrenched itself in English history and memory across a period of several centuries.

W. Ph. Coolhaas, “Notes and Comments on the so-called Amboina,” in M.A.P. Meilink-Roelofsz, M.E. van opstall, and G.J. Schutte, eds. Dutch Authors on Asian History: A Selection of Dutch Historiography on the Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie (1988), 198-240.

Perhaps the best article ever written on the case by one of the giants of Dutch empire scholarship. Concludes that there was a plot but is critical of the way the case was handled.

Anthony Milton, “Marketing a Massacre: Amboyna, the East India Company and the Public Sphere in Early Stuart England,” in Steve Pincus and Peter Lake (eds), The Politics of the Public Sphere in Early Modern England (2007).

A fascinating examination of how the English East India Company attempted to mobilize public and elite opinion around the case.

Giles Milton, Nathaniel’s Nutmeg (1999)

A popular account detailing the English push into Asia.

Connected pages on Not Even Past

Adam Clulow and Tom Chandler, Building a Virtual City for the Classroom: Angkor

Image Credits

Banner credit: Andries Beekman, The Castle at Batavia, c. 1661 (detail, SK-A-19, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam).