Born to an English family in India in 1858, Frederick Lugard rose to become the colonial Governor of Nigeria, Britain’s most valued African possession. His The Dual Mandate, first published in 1922, became a handbook for all British administrators in tropical Africa, and influenced British colonial policies across the continent. It offered a comprehensive evaluation of the nature and challenges of British rule in Africa.

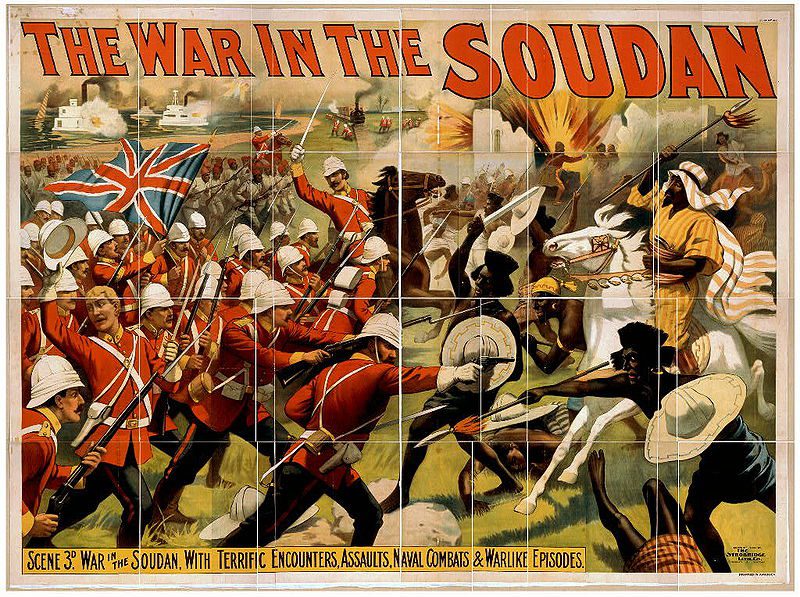

Lugard asserted that the direct cause of Africa’s partition was France’s search for rehabilitation in north and west Africa, following its defeat in the Franco-Prussian war. This ambition resulted in a scramble between France and Germany for African spheres of influence, to which Britain was “unwillingly” compelled to participate. To shield British spheres of influence from external intrusion, the British Foreign Office declared them as Protectorates. Territories acquired through conquest, cession, settlement, or annexation were designated as Crown Colonies. Apart from east and southern Africa, where the terrain and temperate weather offered convenient habitation to European settlers, the African tropics held few incentives for white settlers. However, the region provided abundant sources of raw materials and markets for manufactured goods.

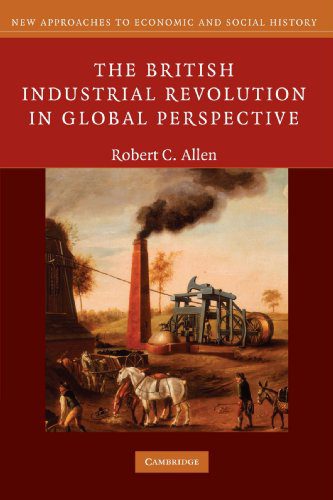

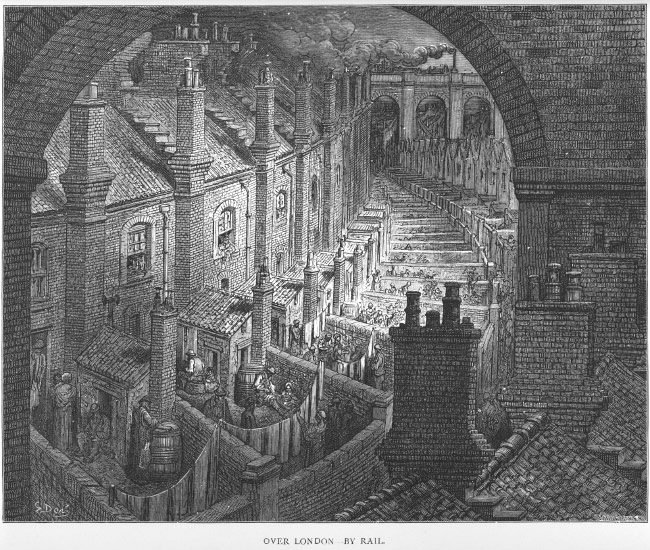

According to Lugard, Britain held a dual responsibility in Africa: administration and economic benefits for the metropole, as well as the “native’s” uplifting. His recommendations for Africa’s governance revolved around three principles – decentralization, continuity, and cooperation. Decentralization at all levels of government, with a strong coordinating authority in the center, allowed for greater efficiency. Continuity was vital because Africans trusted foreigners reluctantly. Therefore, effective British officers should retain their posts without undue interruptions. He also proposed that, during Governors’ annual leaves, they should be represented by a Lieutenant Governor, selected from the Provincial Administrative Staff, rather than the Colonial Secretary. Decentralization and continuity could only be achieved if cooperation existed within the administrative chains, especially between the provincial staff and local rulers. The success of Lugard’s Indirect Rule policy — administration through local chiefs, under the close supervision of British colonial officers — a system that he tested comprehensively in Nigeria, depended on cooperation. He also encouraged local heirs’ education in order to prevent the emergence of a separate educated class that might challenge the authority of accepted rulers. As a way of harnessing the empire’s economic benefits for Britain’s post-World War 1 recovery, Lugard recommended the construction of strategic railways across British Africa. He concluded that British governance offered happiness and welfare to “primitive” peoples. “If unrest and desire for independence exists,” he asserted, “it is because the natives have been taught the value of freedom and independence, which for centuries they had not known.”

Lugard writes in a clear style. His book is a masterpiece of literature and policymaking, though contemporary readers will find his defense of British colonialism in Africa racist and paternalistic. Firstly, he reiterated the supposed unwilling nature of Britain’s involvement in Africa. He blamed Africa’s partition on French and German rivalry, while ignoring that Britain’s economic interests and national prestige hung in the balance too. Secondly, he argued that Britain practiced a beneficent regime that taught Africans the value of freedom and liberty, hence their desire for independence. He ignored colonialism’s oppressive nature and the shortcomings of British rule, which caused protests against the government. He overlooked the “freedom and liberty” existing in indigenous structures, hence the sustained resistance by Africans against European domination. Lugard’s administrative template rules out an independent Africa, free from British control, at least for the indefinite future. Nonetheless, The Dual Mandate in British Tropical Africa is illuminating for readers seeking to understand the foundations of British colonial policies in Africa.

You may also like Ogechukwu Ezekwem’s review of The Making of Man-Midwifery: Childbirth in England 1660-1770

![An image from "Flora Huayaquilensis," a visual collection of South America's plants as seen by Spanish botanist Juan José Tafalla during a 1785 expedition through Peru and Chile. ([Juan Tafalla], “Flora Huayaquilensis,” ourheritage.ac.nz | OUR Heritage - See more at: http://otago.ourheritage.ac.nz/items/show/7696#sthash.r8R9WHhx.dpuf)](https://notevenpast.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/87bbce75b1706f7ba39ef9bcbb7c9560.jpg)