In 1808, Napoleon Bonaparte invaded the Iberian Peninsula, forcing King Charles IV and his son Ferdinand VII to surrender their rights to the Spanish throne. While a brutal war ravaged the peninsula, various municipalities and corporate bodies throughout the Spanish Atlantic World formed juntas (councils) to govern in the absent monarch’s name. This episode opened an unprecedented period of political experimentation that culminated in the fragmentation of the empire and the emergence of new polities. Pamela Voekel’s latest book, For God and Liberty, challenges the notion that this period marked a triumph of secular political modernity. Instead, she reveals how these political transformations were deeply intertwined with broader historical forces.

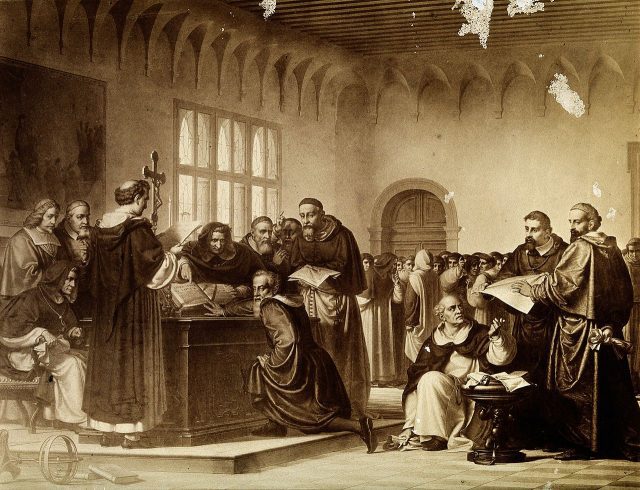

For God and Liberty chronicles the emergence of a religious divide among Catholics in the Spanish Atlantic World. It presents two contrasting factions: Reformist Catholics, who championed a more democratic model of church governance and advocated for a simpler, more austere Church, and Ultramontane Catholics, who fervently defended absolutism and upheld rigid secular and ecclesiastical hierarchies. Voelkel argues that individuals from both factions engaged in expansive intellectual networks, participating in what she terms a “transatlantic Catholic civil war” spanning from the late colonial period through to the post-independence era (1808-1861). She convincingly illustrates that the clashes between these groups stemmed from fundamentally different approaches to biblical exegesis and distinct interpretations of the Church’s early history.

Focusing primarily on Mexico and Central America, Voekel carefully reconstructs the contours of this controversy in seven chapters organized chronologically. The first three chapters are dedicated to the period of imperial crisis. Chapter one examines the debate between Mérida’s Sanjuanistas and Rutinarios. The Sanjuanistas were a faction of the clergy that supported Bourbon initiatives aimed at strengthening a secular clergy under more direct control of the Crown. However, following the promulgation of the Cadiz Constitution in 1812, their positions became more radical, transitioning from autonomists to strong defenders of independence. Chapters two and three delve into the period of independence in Central America, illustrating the impact that religious arguments had on how the actors of that time understood politics. For instance, the Catholic reformist critique on luxury was later deployed by El Salvador’s indigo growing elite to argue from greater autonomy from Guatemala’s merchant guild.

Chapter four through eight focus on post-independence Mexico and Central America. Voekel shows that during the first half of the nineteenth century, both liberal and conservative parties inherited the conflicts from the Catholic reformists and ultramontane Catholics steaming from the era of imperial crisis. However, the emphasis of the debate shifted from popular sovereignty to the extent of civil authorities’ control over ecclesiastical matters, such as the election of archbishops, public expressions of religiosity, and clerical celibacy. Notably, chapter eight contends that the Reforma period in nineteenth-century Mexico, often characterized as a time of radical secularism, was, in fact, a conflict among various factions of Catholics debating the appropriate relationship between the state and the church.

One of the book’s most significant contributions is its reexamination of the role of religion in the history of the public sphere. By analyzing newspapers, pamphlets, speeches, and letters, Voekel illustrates how debates during the early phase of Mexican and Central American liberalism were deeply rooted in religious controversies. Participants in the public sphere, both layman and clergy, did not distinguish between electoral politics and religious discussions. Moreover, the author reveals that the parish church served as a vital conduit for the dissemination of political ideas long before the arrival of the printing press. This evidence enables Voekel to assert that religion was not confined to the private sphere but was, in fact, central to public discourse.

Although this book may not fit neatly into Atlantic history, it compellingly encourages moving beyond the national history framework that has largely influenced the study of Catholicism in Spanish America. For God and Liberty presents fascinating comparisons and highlights unexpected connections among the various participants in this transatlantic Catholic confrontation. For instance, the text illustrates how the arguments advanced by schismatic clerics in the province of Socorro in New Granada (present-day Colombia) for establishing an independent archbishopric and democratically electing their archbishop in 1810 served as a significant intellectual reference for reformist clergy in Salvador and Guatemala during the early years of independence. Similarly, Chapter Four transports the reader across the Atlantic to Rome, following the journey of Salvadoran envoy Victor Castrillo, who sought to negotiate the granting of a new “Patronato Regio” for the Republic of Central America with Pope Leo XIII. In doing so, the book effectively conveys the polycentric nature of these debates, steering clear of simplistic models that place Europe at the center of intellectual production.

For God and Liberty is a timely and valuable addition to the growing body of scholarship that, over the past two decades, has integrated religion into the historiography of the Age of Revolutions, an area where Spanish America has received comparatively less attention. Voekel’s book presents a methodologically rigorous study that demonstrates a deep engagement with both English and Spanish-language authors. I would be interested to know whether dissenting voices existed within the reformist and ultramontane factions, given that historians of nineteenth-century Latin America have highlighted the diversity of political positions within the “liberal” and “conservative” parties. On the whole, however, I recommend this book to anyone interested in the revolutionary era, the history of Catholicism, and popular politics in Latin America.

Juan Sebastián Macías Díaz earned a BA in History from the Universidad de los Andes (Bogotá, Colombia) and an MA in Latino/a and Latin American Studies from the University of Connecticut. Currently, he is a second-year PhD student in the Department of History at the University of Texas at Austin. His research interests include indigenous history and popular politics in the Northern Andes during the Age of Revolutions.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.

by

by