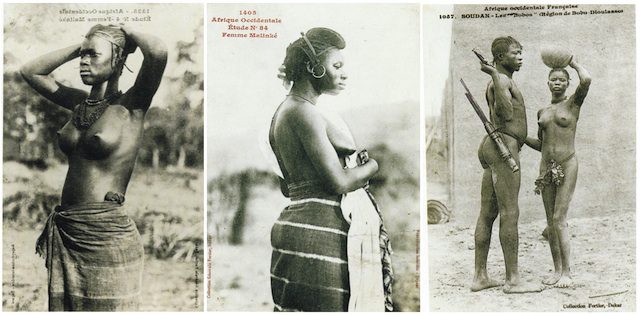

Francois Edmond Fortier (1862-1928) made a very good living working as a photographer in the French West African colony of Senegal. Fortier grew up in eastern France, close to the German border, and by 1899 was living in Senegal where he set up a photographic studio. In the early 1900s he travelled extensively in French Africa, taking pictures wherever he went. In 1908 he was appointed official photographer to French officials touring colonies in the region.

The new and hugely popular postcard industry was thriving at the time Fortier was active and his photographs were mostly transferred to postcards, a business in which he became very active by about 1905. He was an enormously prolific photographer and somewhere between 3000 and 4000 of his images survive. There is even a website devoted to him!

One of the early staples of the new postcard industry was a category often known as the ethnographic postcard. These were pictures of indigenous peoples, taken largely by European and American photographers, and mostly in Asia and Africa. Sometimes they had captions intended to be humorous and pointing to the differences between the viewer at home in the west and the subjects of the card. Sometimes they purported simply to offer an informative and realistic example of a particular people. Such cards often bore the legend “anthropological type” or indicated that the image typified a certain racial or social group.

Among these postcards there was another enormously successful sub-set that depicted people, mostly women, either scantily clad or with no clothes at all. These cards are historically interesting for many reasons. This was, after all, an era in which obscenity laws were on the rise across the west and regulations forbidding the distribution of obscene items (from pornography to contraceptive devices) was a prosecutable offense. The US Congress passed the Comstock Law in 1873 to control the “Trade in, and Circulation of, Obscene Literature and Articles of Immoral Use.” Booksellers who sold risqué photographs as well as literature were vulnerable under Britain’s Obscene Publications Act of 1857, as they were in France after 1811 when Napoleon introduced his Laws against Public Vice. In Germany a new country wide criminal code made the dissemination of obscenity illegal in 1872. Yet despite the crackdown on erotic images that was so common a feature of nineteenth-century law, postcards with nude or semi-nude images of indigenous peoples not only avoided the ban, but could be sent through the mail without fear of prosecution. This was because they marketed themselves as educational, demonstrating different varieties of the human form across the globe, and thus could avoid the taint of pornography that would have attached to them if their subjects were white and European. These cards echoed the displays of “natives” that became so popular at the world’s fairs to which people flocked late in the nineteenth and into the twentieth century.

Edmond Fortier’s photographs of Malinké Women taken in West Africa, 1906. The images are held in the Picasso Archives, Musée Picasso, Paris.

Cards of this sort were enormously profitable for Fortier and many others in Africa, in India, in the Pacific and elsewhere. Fortier’s business was among the most voluminous and his work found its way into the collections of none other than the celebrated modernist artist, Pablo Picasso. Some forty Fortier postcards, mostly of bare-breasted women, are among the many ethnographic cards Picasso seems to have amassed in the early years of the twentieth century. His extensive Fortier collection dates from the time when he was painting what would become his most ambitious canvas to date, one that would rock the art world, and remains to this day among his most controversial and also his most emblematic paintings, Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. It’s a huge painting, almost 8’ by 8’, depicting five naked Spanish brothel workers. The two on the far right are wearing African masks. The picture was completed in 1907 and the postcards date from 1906. The painting signaled where his art was headed with its break from traditional representation and perspective. Most art historians associate the painting with the beginning of what became known as Primitivism, western art that included what were regarded as non-western art forms from societies that, at the time, would have been considered less advanced than colonial western powers.

Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907) by Pablo Picasso. Courtesy of The Museum of Modern Art / Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY.

French art historian and former director of the Picasso Museum in Paris, Anne Baldassari, claims that Picasso used his collection of Fortier postcards to produce these startling and striking images. The exhibition where she made this claim debuted to great acclaim at Houston’s Museum of Fine Art in 1997 under the title Picasso and Photography: The Dark Mirror. In the exhibition, she traces Picasso’s use of photographic images to model his paintings, as well as his own enthusiasm for photography, both good examples of the changes new visual technologies augured in the art world. In the poses and the demeanor of the women in Picasso’s canvas she sees a reflection of the bold stares of the women in the postcards, expressing attitudes that at the time would have been unthinkable for European women.

French art historian and former director of the Picasso Museum in Paris, Anne Baldassari, claims that Picasso used his collection of Fortier postcards to produce these startling and striking images. The exhibition where she made this claim debuted to great acclaim at Houston’s Museum of Fine Art in 1997 under the title Picasso and Photography: The Dark Mirror. In the exhibition, she traces Picasso’s use of photographic images to model his paintings, as well as his own enthusiasm for photography, both good examples of the changes new visual technologies augured in the art world. In the poses and the demeanor of the women in Picasso’s canvas she sees a reflection of the bold stares of the women in the postcards, expressing attitudes that at the time would have been unthinkable for European women.

Postcards depicting white women without their clothes on would not so easily have avoided the censorship that the new obscenity laws were busily imposing in western nations. But images of non-western women, and especially women from areas considered primitive and sexually bold, were, it would seem, available not only to the purveyors of smutty postcards dressed up as educational materials but to the priests of high art. Picasso’s painting is a magnificent and an important work but if Baldasseri’s hunch is right, it’s also the product of a world that profited from maintaining a huge divide between a civilized west and a primitive and sexualized other.

Further Reading

Anne Baldassari, Picasso and Photography: The Dark Mirror (Paris and Houston: Flammarion, The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston 1997)

Christraud M. Geary and Virginia-Lee Webb, ed. Delivering Views: Distant Cultures in Early Postcards (Washington and London, Smithsonian Institution Press, 1998)

Full image credit for Les Demoiselles d’Avignon by Pablo Picasso: ‘Picasso, Pablo (1881-1973) ARS, NY. Les Demoiselles d’Avignon. Paris, June-July 1907. Oil on canvas, 8′ X 7’ 8″ (243.9 x 233.7 cm). Acquired through the Lillie P. Bliss Bequest. Estate of Pablo Picasso/ Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Digital Image courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art/ Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY.