What occurs when elite driven narratives about national identity dramatically different differ from the realities people experienced? During the nineteenth century throughout Latin America, when national boundaries were just beginning to become coherent, the upper echelons of society constructed tales about their nations that often vastly differed from lived experiences.

What occurs when elite driven narratives about national identity dramatically different differ from the realities people experienced? During the nineteenth century throughout Latin America, when national boundaries were just beginning to become coherent, the upper echelons of society constructed tales about their nations that often vastly differed from lived experiences.

Between 1850 and 1859, the Chorographic Commission traveled the territory of present day Colombia in an attempt to map the land and the people who lived there, using chorography, or detailed representations of a particular region. Sponsored by the government of New Granada (an older name for Colombia), the commission produced a wealth of maps, texts, illustrations, as well as travel journals and diaries, in order to construct the image of a unified nation. Implicit in the commission’s initial mandate was the assumption that it would justify the existing administrative order by making that order appear natural.

The visual culture it produced, however, depicted a nation that was far from cohesive, with regional individuality and diversity. Instead of portraying a unified nation, the commission presented the country as fragmented into different, and often opposing regions, inhabited by racially and culturally distinct races, that reinforced assumptions of Andean and white mestizo superiority. In this new book, Nancy Appelbaum expands our understanding of this central paradox, demonstrating that the commission’s materials reveal some of the ways that Colombian elites grappled with the challenges posed by varied topographies and diverse inhabitants.

The leaders of the Chorographic Commission included both foreign members and others who were born and bred in New Granada. Two of the key figures on the commission, whose writings play an important role throughout the book, were Agustín Codazzi and Manuel Ancízar. Born in Italy’s papal states and a Napoleonic war veteran, Codazzi was in fact first contracted to map the Venezuelan provinces, which had seceded from Gran Colombia, in 1830. The secession precipitated Gran Colombia’s dissolution into Venezuela, Ecuador, and New Granada. Manuel Ancízar, a Colombian lawyer, writer, and journalist, joined Codazzi on the Commission in 1850.

Using personal correspondence between Codazzi and Ancízar, Appelbaum argues that although the creation of the commission reflected nationalist aspirations of the government, it was fundamentally shaped through its leaders’ own exposure to foreign culture. The geographic writings of Prussian Alexander von Humboldt, as well as Italian Adriano Balbi, strongly influenced Codazzi’s and Ancízar’s initial overviews, as they “draped themselves in the ‘mantle of Humboldtianism’ to emphasize their own scientific legitimacy.” Inspired by Humboldt, Codazzi divided the terrain of New Granada according to the differing altitudes, winds, and vegetables that he encountered. The ideological influence of Humboldt, together with Balbi’s schematic list methodology, helped the Commission create a novel and distinct approach to chorography that was more affordable than the fashionable trigonometric survey.

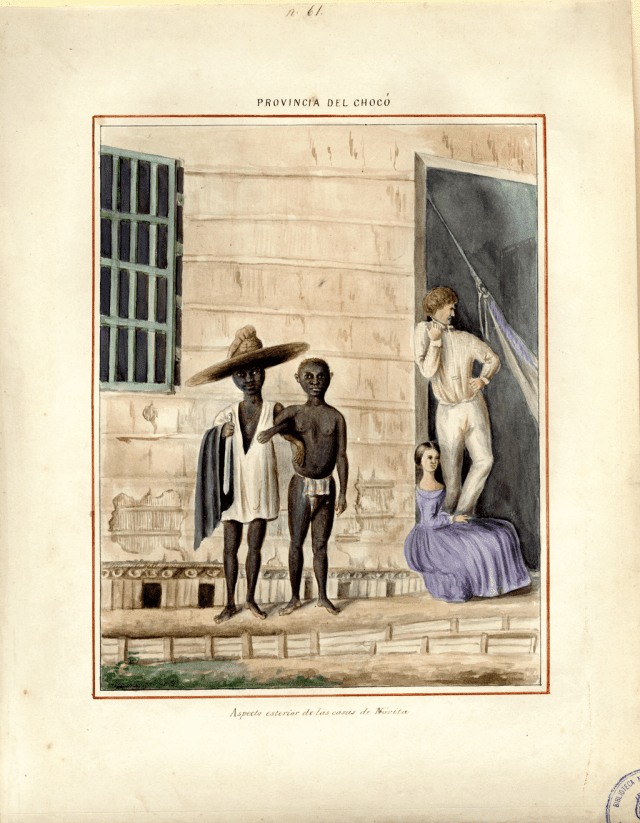

The detailed accounts produced by Codazzi and Ancízar on the commission’s initial expeditions to the highland region of Antioquia and the Pacific lowland, comprised not only field reports, but also included detailed watercolors created by the commission’s first illustrators in order to depict the populations they encountered. Through comparing the perceptions noted in the field reports with the pictorial representations, the tension comes out between the inclination to show these regions as homogenous when the commission clearly experienced great heterogeneity of the people and customs.

William Price, Typical Inhabitants of the Province of Medellín (via World Digital Library).

This visual culture reflected a literary and artistic current in nineteenth-century Latin America called costumbrismo, or using descriptive prose and dialogue to verbally paint a local scene, emphasizing the customs and particularities of that locale. Within these works, tipos “types” that organized the population into component parts defined by race, occupation, and place, were created to provide both a visual and discursive way to manage the heterogeneity that the commission encountered. In William Price’s Tipos de Medellin, the commission’s artists displayed idealized images of people one would encounter when visiting these places. These images of the racial types that the commission produced updated the eighteenth-century genre of casta paintings for the republican era.

As the commission moved into the tropical lowlands and the eastern plains, Appelbaum further elaborates how the illustrations were largely aimed at an external audience in order to attract immigrants and economic investment to the region. The commission’s efforts were not meant to simply represent the landscape, they were also to transform it in the service of economic advancement. Codazzi believed that these areas, rich in agriculture and livestock, could support many more people than their sparse, midcentury population. Elites defined the tropics, for instance, as being filled with disease, poverty, and backwardness, making it a desirable region for colonization and improved methods of production. The commission took on an ethnographic dimension, as studying the population became an integral part in determining the economic capabilities of the land. Reports, maps, and paintings that Codazzi, Ancízar, and others, produced provided abundant information aimed to facilitate the conquest of the regions they mapped and studied.

Manuel María Paz, Provincia del Chocó: Aspecto esterior de las casas de Nóvita (via World Digital Library).

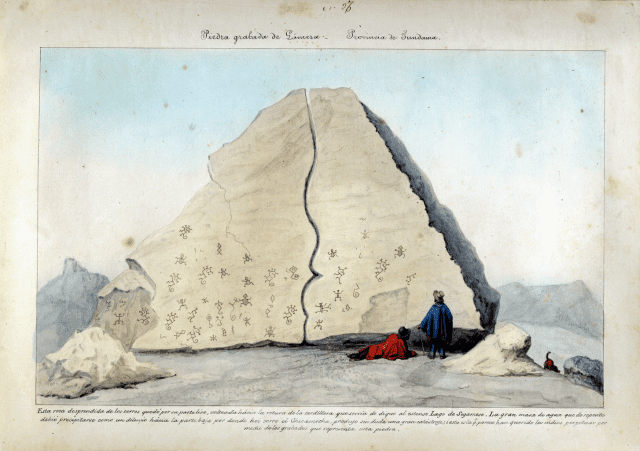

Applebaum goes on to discuss the methods that mid-nineteenth-century intellectuals living in the highlands around Bogotá employed to rationalize their claim over the local populations. By emphasizing the glorious origins and civilization of the Andean region around Bogotá, at the expense of lower “savage” climates, intellectuals reinforced Bogotá’s claim over this topographically disparate territory. Codazzi projected national history into the ancient past by weaving geology, archeology, and history together and referencing the past as “history” rather than prehistory. They placed themselves, not the local indigenous populations, who ultimately were the Commission’s guides, at the top of the intellectual scale to read the cataclysmic past.

Carmelo Fernández, Piedra grabada de Gámesa. Provincia de Tundama (via World Digital Library).

After Codazzi died in 1859, elites left behind tried to make sense of his project and battled each other over meanings and representations of the nation. Although members of the commission had high hopes for the mass reproduction and circulation of the materials they produced, that did not occur. Chorography and the work of the Chorographic Commission died with Codazzi, supplanted later in the nineteenth century by newer forms of mapping which are still common today, such as topography.

Although the work that the Chorographic Commission created between 1850 and 1859 was not as widely received as hoped, the spatialized and racialized regional hierarchy inherent in its visual materials would be reproduced and refined within Colombian scholarly and popular discourse. By no means the originator of this fragmented discourse, the Commission’s cartographic project formed the basis for most maps of Colombia into the early twentieth century.

Gracefully written, integrating over thirty images and maps, Mapping the Country of Regions offers a fascinating window into both the visual culture produced during the nineteenth century in Colombia, and the ways that territories, boundaries, and state-lines are constructed. Appelbaum’s contextualization of her source base that she makes explicit within her analysis heightens her claims about the use of geographic, ethnographic, and visual methods to secure territory. This theme of racialization of geographic hierarchy is not solely limited to Colombia, as ideas about how race and region have historically informed each other throughout Latin America. The blending of analysis with visual representation enables this book to be of use for those interested in not only Latin American nation-state building, but this methodology of combining visual and textual analysis would be of value for anyone incorporating visual culture into their own work.

Nancy P. Appelbaum, Mapping the Country of Regions: The Chorographic Commission of Nineteenth-Century Colombia (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2016).

![]()

Also by Madeleine Olson on Not Even Past:

A Texas Historian’s Perspective on Mexican State Anticlericalism.

You may also like:

Antonio de Ulloa’s Relación Histórica del Viage a la America Meridional, by Haley Schroer.

Casta Paintings, by Susan Deans-Smith.

![]()

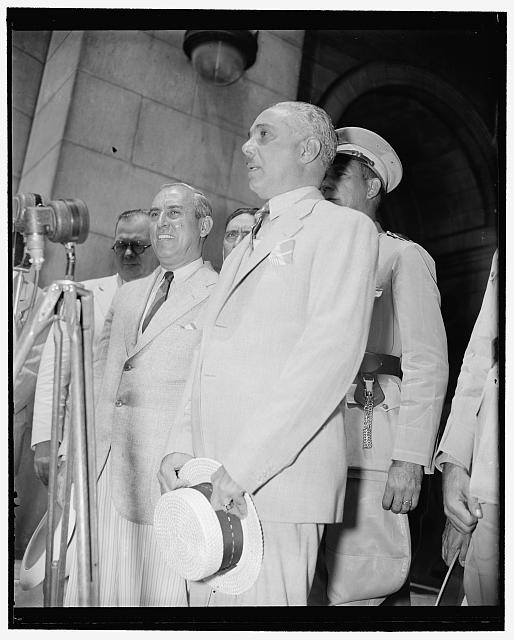

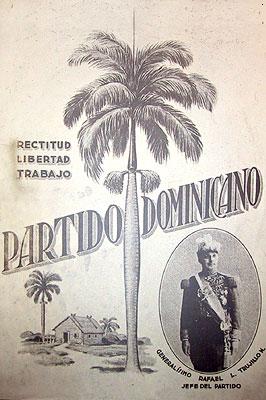

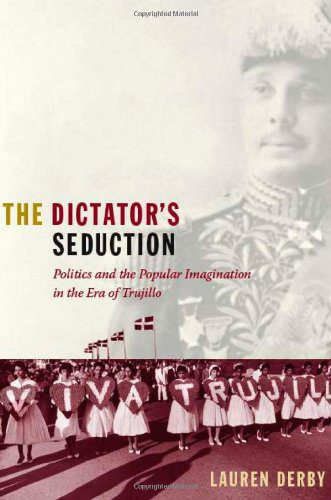

A light-skinned mulatto with Haitian ancestry, Trujillo rose from obscurity as a sugar plantation guard to establish one of Latin America’s most enduring dictatorships. His appetite for women was legendary and common belief held that he never sweated. Trujillo’s minions, and even foreign governments, lavished him with praise and an array of titles from Generalissimo to Benefactor of the Fatherland to Restorer of Financial Independence. However, outside portrayals of Trujillo as a make-up wearing megalomaniac and revelations of his regime’s oppression, many questions remain about the mechanisms of state power and relations between the Dominican populace, Trujillo, and the state. In The Dictator’s Seduction, Lauren Derby uncovers the cultural economy “that bound Dominicans to the regime.” She reinterprets the regime’s theatricality – pageants, parades, and the practices of denunciation and public praise – as critical in obscuring the inner workings of the regime and argues that the Trujillato gained and maintained the support of the masses, albeit in attenuated form, by creating a new middle class and co-opting Dominican understandings about the embodiment of race, gender, sexuality, and the process of community formation.

A light-skinned mulatto with Haitian ancestry, Trujillo rose from obscurity as a sugar plantation guard to establish one of Latin America’s most enduring dictatorships. His appetite for women was legendary and common belief held that he never sweated. Trujillo’s minions, and even foreign governments, lavished him with praise and an array of titles from Generalissimo to Benefactor of the Fatherland to Restorer of Financial Independence. However, outside portrayals of Trujillo as a make-up wearing megalomaniac and revelations of his regime’s oppression, many questions remain about the mechanisms of state power and relations between the Dominican populace, Trujillo, and the state. In The Dictator’s Seduction, Lauren Derby uncovers the cultural economy “that bound Dominicans to the regime.” She reinterprets the regime’s theatricality – pageants, parades, and the practices of denunciation and public praise – as critical in obscuring the inner workings of the regime and argues that the Trujillato gained and maintained the support of the masses, albeit in attenuated form, by creating a new middle class and co-opting Dominican understandings about the embodiment of race, gender, sexuality, and the process of community formation.