Not Even Past and AVAnnotate will soon be partnering to develop new collaborative initiatives that connect readers with NEP content. More to come.

The first historical recordings that piqued my interest were made by my fellow Floridian Zora Neale Hurston in a studio in Jacksonville, Florida, in 1939. Recorded on June 18 at the Federal Music Project Office of the Work Projects Administration (WPA) with Carita Doggett Corse, Herbert Halpert, and Stetson Kennedy, these are unusual and rich texts to study. They document a Black, female ethnographer performing African American stories and songs for a White audience, both in the recording studio, where her fellow ethnographers can be heard asking her questions, and for the white listeners at the Library of Congress who would later receive the recordings. These 1939 recordings are shockingly well-produced (even as they are sometimes difficult to understand) and are now digitized and online. All of these factors make recordings like these interesting artifacts. They include the circumstances of the recording, the transposition of the original acetate disks onto reeltoreel tapes, their digitization, and how curators described them in catalogs that now form the metadata through which they are discoverable in the archive and online.

Zora Neale Hurston with Rochelle French and Gabriel Brown, Eatonville, Florida, June 1935. Photograph by Alan Lomax. Courtesy of Library of Congress

It can be difficult for scholars, students, and the public to use audiovisual (AV) collections at libraries, archives, and museums (LAMs) in research and teaching. Because accessing these materials often requires specialized equipment, expertise, and time, LAMs with diverse AV collections might not prioritize their preservation. In addition, LAMs report that there are few accessible technologies and examples for how to use digital AV cultural heritage materials in the classroom, in research, or in public contexts.[1] LAMs remain in the early stages of working through the politics, protocols, and systems of access.

I’m trained primarily in textual studies and modernist literature, but I’ve spent many years using and creating digital tools with all kinds of texts (including print documents, manuscripts, and audio recordings). Reflecting on the significance of archival audio recordings to literary study is the focus of my recent book, Dissonant Records: Close Listening to Literary Archives. It seems ironic to write a print book about sound recordings, but it is technically much simpler to teach and do research with text in print. You can hand it around; you can mark it up with underlines and words in the margins like “interesting!” You can highlight key passages or moments and use them to support discussion and interpretation. Scholarly editions have long fulfilled this role for textual sources in a formal, institutionalized way; more recently, digital editions and exhibits have served a similar function. Still, I wanted a way to directly share the context (and my thoughts about it) around underutilized and culturally important AV collections like those I write about in my book.

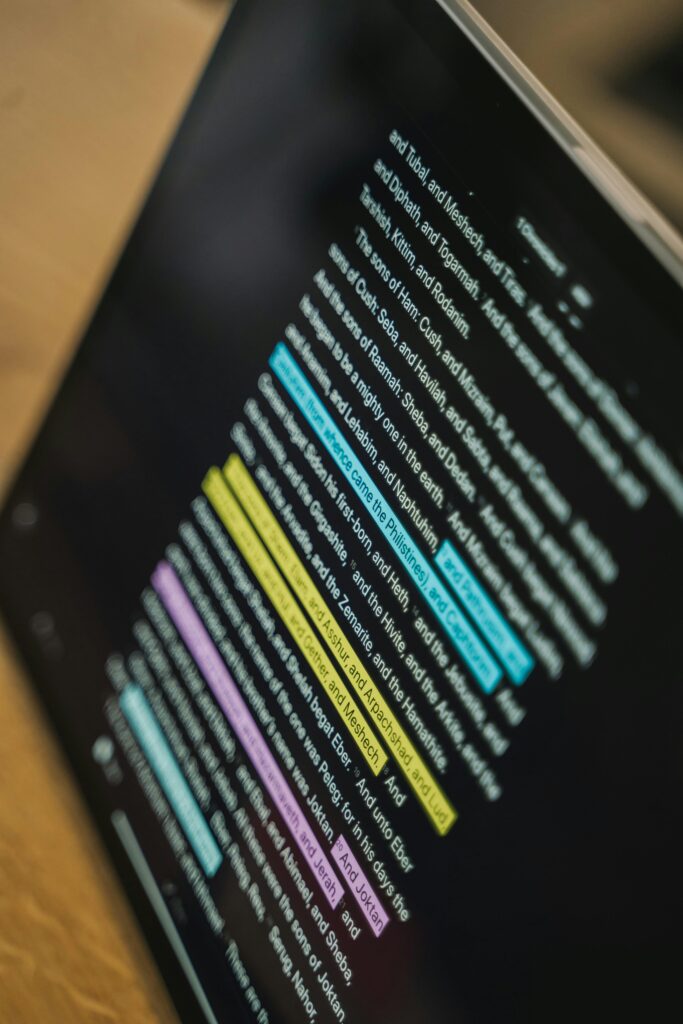

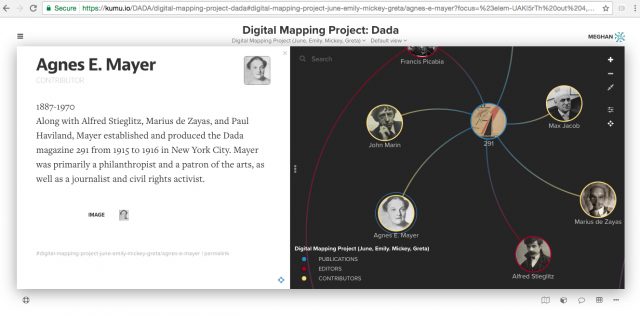

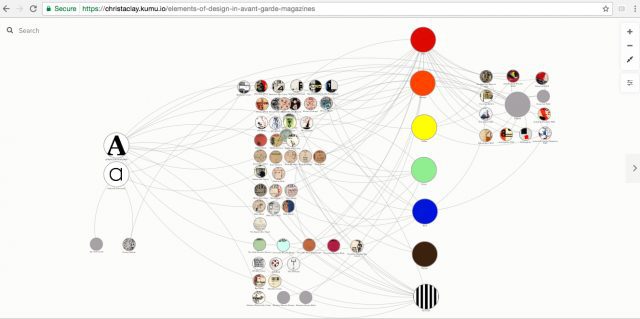

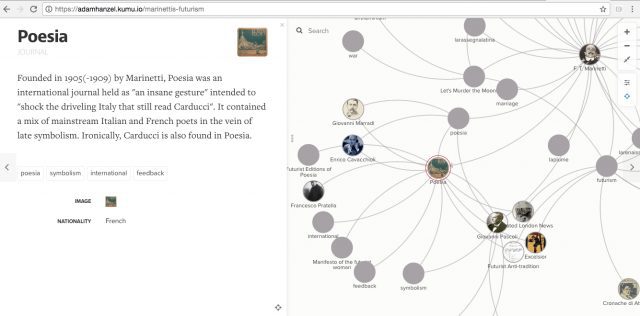

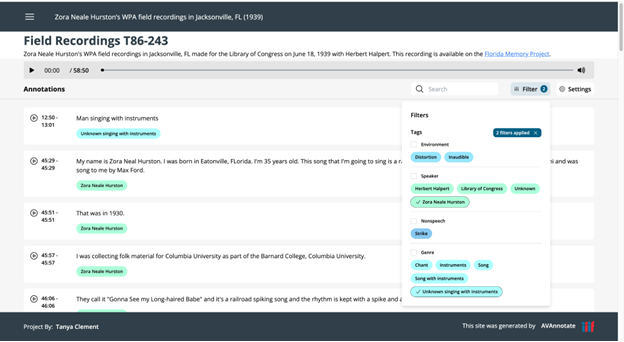

To achieve this, I developed AVAnnotate with the help of my team and the support of funding from the American Council of Learned Societies and the Mellon Foundation. AVAnnotate facilitates making projects with an AV player and user-generated annotations. Plus, adding essays, notes, and index terms served my needs as a scholar and teacher and helped me tell my story about these recordings. There are more technical details in the documentation, but some of the principles behind the technical development include that AVAnnotate is open-source software that leverages the International Image Interoperability Framework (IIIF)[2] standard for AV materials and GitHub in a minimal computing workflow[3] that simplifies creating standards-based, user-generated, online projects. These principles underlie an easy-to-use dashboard on the backend where users can create AVAnnotate annotations that take four forms in the published project (see Figure 1). There are (1) long-form notes that could be transcriptions (see “My name is Zora Neale Hurston . . . “ or more like the sort of marginalia one might find in a print scholarly edition (see the note beginning “Man singing with instruments . . .”); (2) index terms or “tags” (such as “Zora Neale Hurston,” “Song,” or “Unknown singing with instruments”) that facilitate organizing, searching, and visualizing types of annotations and important concepts; (3) tag groups to further facilitate filtering groups of tags (e.g. “Environment,” “Speaker,” and “Nonspeech”); (4) timestamps (e.g., 12:50-13:01) that help situate the notes and index terms. These kinds of annotations mark how and to what we listen in these recordings, just as editorial choices and marginalia notes mark how and what editors and authors find significant in specific versions of manuscripts and printed texts.

Figure 1: AVAnnotate page from “Zora Neale Hurston’s WPA field recordings in Jacksonville, FL (1939)”

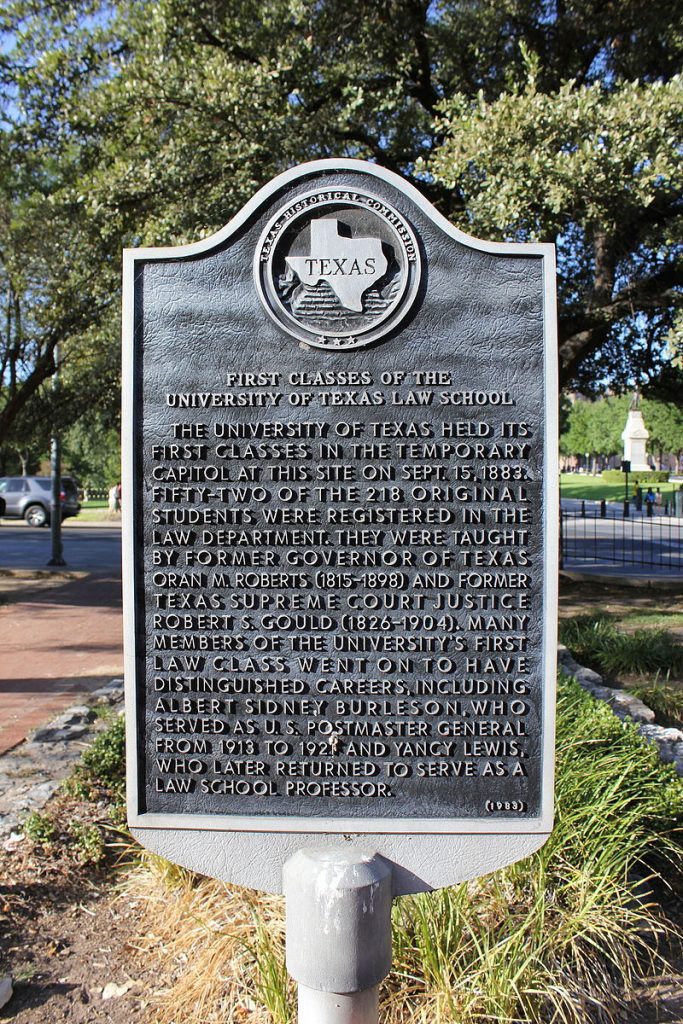

Collecting institutions, researchers, teachers, and the public have used AVAnnotate for a variety of purposes in their desire to make AV more accessible. Librarians from the Benson Latin American Collection at the University of Texas at Austin have created multiple exhibits. Some projects highlight radio programs, including the Latin American Press Review Radio Collection to showcase radio programs from the Longhorn Radio Network airing from 1973 to 1974 that covered all of Latin America and the Caribbean, and Radio Venceremos, the rebel radio station that broadcast from the mountains of Morazán, El Salvador, during the eleven-year Salvadoran Civil War (1981-1992). Benson librarians and I have also used AVAnnotate to share recordings from historical symposia, including the Benson’s Speak-Out! Charla! Bate-Papo! Contemporary Art and Literature in Latin America Symposium held October 27-29, 1975, at the University of Texas at Austin (transcriptions provided in both English and Spanish), and my own edition of the Harvard 1953 Summer Conference on “The Contemporary Novel,” which includes recently discovered recordings of panels and lectures from literary luminaries such as Ralph Ellison.

Researchers have used AVAnnotate to discuss historical cinema, poetry readings, podcasts, and oral histories. Jack Riordan created a bilingual AVAnnotate project around his interviews with Cuban filmmaker Lester Hamlet, exploring Hamlet’s poetry, archival materials, and cultural contexts. He also developed a separate project on Auteurism, examining the theory through filmmakers such as Stanley Kubrick, Wes Anderson, Tomás Gutiérrez Alea, Andrei Tarkovsky, and Akira Kurosawa. In addition to oral histories, interviews, and cinema, other projects showcase research around poetry readings and podcasts. Of special note, researchers from the SpokenWeb partnership created the SpokenWeb UAlberta in 360° to present a fusion of past and present technology. This project brings together artifacts created for and at the 2025 SpokenWeb Sound Institute, with special emphasis on author reactions to a 360° video made of author reactions to literary recordings from the 1960s-1980s played back on a 1960s Sony TC-102 portable reel-to-reel tape player in the same Edmonton locations where they were originally recorded decades earlier.

Educators in particular find AVAnnotate useful both for teaching students about historical AV recordings and for giving students the opportunity to create their own projects. The Educational Project for John Beecher, McComb “Criminal Syndicalism” Case project is an example of working with and annotating sensitive audio using a recording from the John Beecher Sound Recordings Collection at the University of Texas’s Harry Ransom Center. In this recording, John Beecher and members of the Council of Federated Organizations (COFO) meet with high school students arrested on charges of criminal syndicalism after their release from jail in McComb, Mississippi, on October 19, 1964. The project includes: the audio annotated with research about the recording’s social and historical context and a full transcription; two lesson plans for instructors to use AVAnnotate and this recording in a high school classroom with one in-person and one asynchronous lesson plan; the asynchronous, student-facing lesson that is ready to use in the classroom; and an example student collaborative project that teachers could build by the end of either lesson. Other projects are the result of students in a cinema class creating a project about Identity and Embodiment in the Stella Adler Collection, the RHE 306 Anthologydeveloped by students asked to produce original audio or video compositions paired with annotations and a transcript that examine rhetorical strategies, and the Literary Sound Studies: English 483 Class Anthology where student annotations represent an analysis of voice, rhythm, silence, and audience with a focus on how literature is performed and heard.

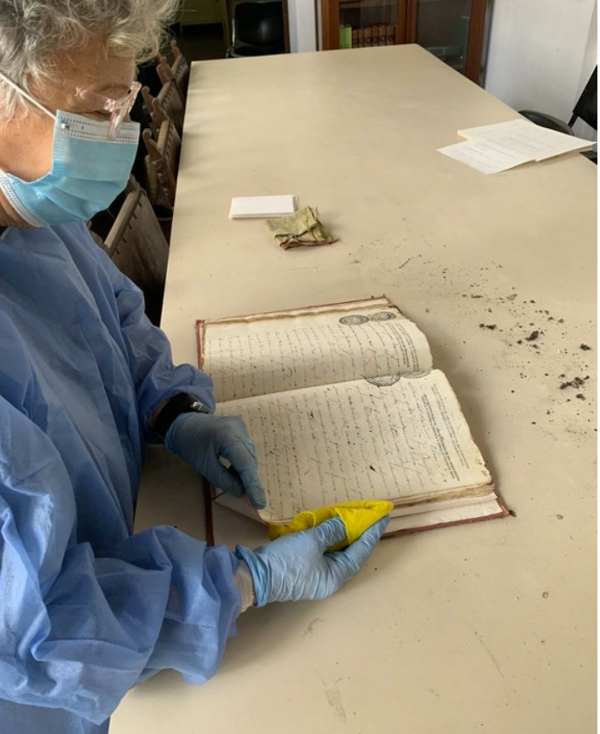

AVAnnotate is currently released as a stable version. Our resources include documentation, examples, and tutorials. Our general user guidelines have been developed for Collecting Institutions, Researchers, Educators, and the Public. Additionally, the AVAnnotate team has collaborated with partnering organizations including a community of scholars, information professionals, and teachers to produce Principles of Engagement that discuss guidelines around using tools like AVAnnotate to create contextual information for AV artifacts outside of collecting institutions where they have been processed, preserved, and made accessible. The kind of “round-trip” sharing of resources—from libraries, archives, and museums (LAMs) to the community and back into the LAM system—that AVAnnotate has the potential to create inspires a technical and social ecosystem that will increase the responsible use and sustainability of cultural heritage AV. My hope is that AVAnnotate encourages more ethical, human-centered, and community-shared approaches to knowledge production.

Tanya E. Clement is the Director of the Humanities Institute and the Robert Adger Law and Thos. H. Law Centennial Endowed Professor in Humanities in the Department of English at the University of Texas at Austin. Her primary areas of research are textual studies, sound studies, and infrastructure studies as these concerns impact academic research, research libraries, and the creation of research tools and resources in the digital humanities. In her most recent project, AVAnnotate, funded by the Mellon foundation, she seeks to increase access to AV recordings in research and teaching by developing an application and a workflow for presenting user-generated, digital editions and exhibits with AV. Her book Dissonant Records: Close Listening to Literary Archives was published by MIT Press in August 2024.

[1] Council on Library and Information Resources (CLIR) and the Library of Congress. The State of Recorded Sound Preservation in the United States: A National Legacy at Risk in the Digital Age. Washington DC: National Recording Preservation Board of the Library of Congress, 2010.

[2] IIIF is a standardized solution that libraries and archives have adopted to give users the ability to perform scholarly methods for research and teaching using third-party platforms like AVAnnotate. More information on the IIIF background to the beta-version of AVAnnotate (AudiAnnotate) is discussed in https://www.digitalhumanities.org/dhq/vol/16/2/000586/000586.html.

[3] See Clement, Tanya, et al. “The AudiAnnotate Project: Four Case Studies in Publishing Annotations for Audio and Video.” Digital Humanities Quarterly, vol. 016, no. 2, June 2022.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.