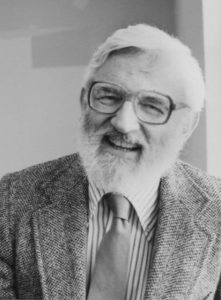

Photo of Alfred Crosby (via Washington Post)

By Megan Raby

This essay is adapted from Dr. Raby’s remarks at a symposium to honor Al Crosby that was sponsored by the Institute for Historical Studies at UT Austin on February 4, 2019.

Alfred Crosby’s work has been with me for a long time––actually longer than I can remember. I routinely assign Ecological Imperialism in my undergraduate course on Global Environmental History, but long before I had ever read that book, I had unknowingly encountered his work. That is, of course, through the concept of the “Columbian exchange”––also the title of his most influential book. By the time I went to elementary school, this once revolutionary way of framing the role of disease, crops, weeds, and domestic animals as central to world history was presented simply as common knowledge.

By putting environmental history at the center, Crosby replaced the older narrative of conquest with a narrative of biocultural encounter and exchange. Instead of a one-way process largely determined by European might, Crosby showed the importance of, on one hand, the great tragedy of virgin soil epidemics and indigenous demographic collapse and, on the other, the ongoing story of how the crops domesticated by the indigenous peoples of the Americas remade the landscapes and cultures of the rest of the world.

In many ways, I think we take this narrative shift for granted today. But to be taken for granted in this way is, I think, a major accomplishment for any historian…perhaps especially for an environmental historian. Even as the field continues to be one of the most rapidly growing subfields of history, many environmental historians still fear that their work remains on the fringes. Is environmental history still seen as a novelty or fad? Do our colleagues take the field seriously enough, say, to give pigs and dandelions a key place in a survey course on U.S. or world history?

Al Crosby’s feat is all the more impressive because he was essentially writing “environmental history” before there was such a thing. In interviews, he often pointed out that half a dozen presses rejected The Columbian Exchange before it finally got published in 1972––its biological perspective on European contact with the Americas was seen as just too arcane of a subject.

But only a few years later Crosby could be counted among the first generation of self-described environmental historians. Crosby was one of the founding members of the American Society for Environmental History, for example, when it was founded in 1977. There was now a new group of scholars who insisted on taking nature seriously as an actor in human history––focusing not on military conquests or presidential politics, but rather on how humans and nature have fundamentally shaped and reshaped each other.

Crosby was no longer alone, but he still stood out. And the ways in which he stood out reveal the lasting impact and relevance of his contributions.

For one thing, it is important to note that the other major founders of environmental history were, for the most part, focused on the United States and especially U.S. Western history. In contrast, Crosby’s work was truly global in scope. Rather than the one-way story of European expansion, The Columbian Exchange shows us New World crops remaking Europe, Africa, and Asia. And with Ecological Imperialism, he tested his thesis about the interplay of ecology and empire not just in the Americas, but with cases everywhere from the Canary Islands to Iceland and New Zealand. In fact, in all his books––on everything from the rise of quantification to the history of energy––Crosby explored truly global exchanges and transformations.

Some of the most groundbreaking work in transnational African and Latin American environmental history in the 1990s and 2000s––works that are themselves now classics––were in fact directly inspired by aspects of Crosby’s arguments. Elinore Melville explored the process of ecological imperialism beyond the temperate zone, by following Spanish sheep into sixteenth-century Mexico. James McCann showed how New World maize became an African staple, adapted to local cultures and climates. Judith Carney argued that rice culture in the Americas took more than just the movement of seeds; its success was dependent on the enslaved Africans who worked in the rice fields and their agricultural experiences and knowledge. These works took the interconnections between biology and cultural knowledge that Crosby himself emphasized, but pushed them into new contexts and new corners of the world.

With the sole exception of his book on the 1918 flu pandemic, Crosby’s temporal scale was as grand as his geographical scope. Recently, there has been a surge of self-described “Big Histories” or “Deep Histories” that view human history and the present through the lens of evolution, neuroscience, or even cosmology.

Crosby was doing “Big” and “Deep” history well before the arrival of these studies. The full title of Ecological Imperialism notes that it starts in 900, but in fact, its explanatory frame extends back beyond the Norse expansion into the North Atlantic. It begins 200 million years ago, with the breakup of the supercontinent of Pangaea, and, hence, the beginning of the evolution of quite distinct biogeographic realms in the Old and New Worlds.

This event was cataclysmic because it brought human and geological history into the same frame, in Crosby’s words:

“The seams of Pangaea were clos[ed], drawn together by the sailmaker’s needle. Chickens met kiwis, cattle met kangaroos, Irish met potatoes, Comanches met horses, Incas met smallpox––all for the first time.” (131)

This, Crosby explains––along with the penchant of Old World humans for living at close quarters with domesticated animals––was the ultimate cause of that immunological difference that made the Columbian exchange so unequal and allowed the empires of Europe their sweeping success in lands with similar climates.

Crosby brought in Pangea and the Paleolithic, but unlike some “Big Histories,” he was not trying to write a history of everything. Nor, I think, did he reduce history to geological and biological science. The scope, scale, and interdisciplinary nature of his work flowed necessarily from the kinds of questions he asked. These were indeed big questions, and also fundamentally historical questions––questions about human agency, about global inequalities in power, and about the roots of global imperialism.

At a time when others might attribute the spread of European empire to “their superiority in arms, organization and fanaticism,” Crosby had the audacity to ask, in the Prologue of Ecological Imperialism, “but what in heaven’s name is the reason that the sun never sets on the empire of the dandelion?” (7)

In the years since, authors like Charles Mann and Jared Diamond have sold many books repeating or updating aspects of Crosby’s argument. Other authors have dug deeper into the theoretical frameworks he offered, building on and extending them. One example is Stuart McCook’s new work on the “neo-Columbian exchange”––by which he means a second wave of globalization of crops and plant pests since 1700, mediated by imperial scientific institutions and global corporations. Likewise, UT History PhD, Gregory Cushman, has explored the role of fertilizer in enabling a process of “neo-ecological imperialism”––the importation of nutrients and energy from far away ecosystems to prop up a new crop of colonial powers. Not coincidentally, both authors place seemingly mundane historical objects at the center of modern history––a common approach today in global histories, after Crosby’s dandelions–for McCook it is the humble cup of coffee, for Cushman it is bird poop!

In many of these direct and more subtle ways, Crosby’s influence is indelible. Crosby helped to make mosquitos and sheep a respectable topic for historians––something that might even have something to tell us about “big questions,” like the rise and fall of empires.

I really regret that I never got a chance to meet him in person. At the same time, in some ways I feel almost like I have met him because, much more than most academic writers, Crosby’s personality, his great enthusiasm for his topics, and his often wry sense of humor shine through in his writing. Crosby’s voice and approach live on as much in the expanding new scholarship of environmental history as in his own body of work––as pervasive, permanent, and familiar in the historical landscape as the plentiful dandelions that sparked his imagination.

Other Articles You Might Like:

Climate Change in History

Her Programs Progress

Crimes Against Nature: Squatters, Poachers, and Thieves, and the Hidden History of American Conservation

Other Articles by Megan Raby:

Enclaves of Science, Outpost of Empire

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.