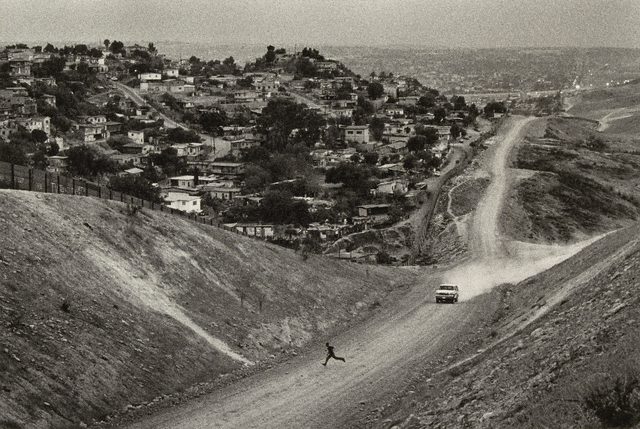

Drug trafficking – especially as it pertains to Mexico – has been a main fixture in today’s news for some time now. But UT graduate student Edward F. Shore argues that the violence, disorder, and political, social, and economic instability associated with the drug trade has a long history, and one that has had international repercussions. Shore’s website “Narco-Modernities” shows that while drug-related episodes may take place in specific countries or regions, the people, governments, economies, and societies they have affected and continue to affect span the globe. Through book reviews, primary sources, maps, secondary historical literature and the author’s own original commentary, “Narco-Modernities” discusses current events while also engaging historical debates surrounding globalization, immigration, crime, gangs, prisons, the “War on Drugs,” the Cold War, and present-day U.S.-Latin American relations.

Nicaraguan Contras

An August 23, 1986 e-mail message from Oliver North to Ronald Reagan and National Security Advisor John Poindexter. In it, North describes his meeting with Panamanian Leader Manuel Noriega’s representative. “You will recall that over the years Manuel Noriega in Panama and I have developed a fairly good relationship,” North writes before explaining Noriega’s proposal. He notes that if U.S. officials can “help clean up his image” and lift the ban on arms sales to the Panamanian Defense Force, Noriega will “‘take care of’ the Sandinista leadership for us.”

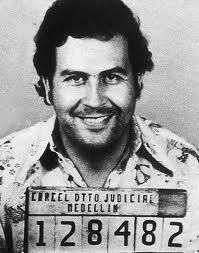

“Godfather of Cocaine” Pablo Escobar’s mug shot

A recently declassified Department of State briefing paper from Inter-American Affairs. It showcases Washington’s frustration with the Guatemalan government’s failure to investigate the a surge of violence, assassinations, and an attack on an American citizen in that country. The United States was particularly concerned about the Guatemalan government upholding human rights, implementing judicial reform, and monitoring drug trafficking but felt that “it can continue to be unresponsive to [its] interests.”

University of Texas at Austin – Department of History

(Professor: Jeremi Suri)

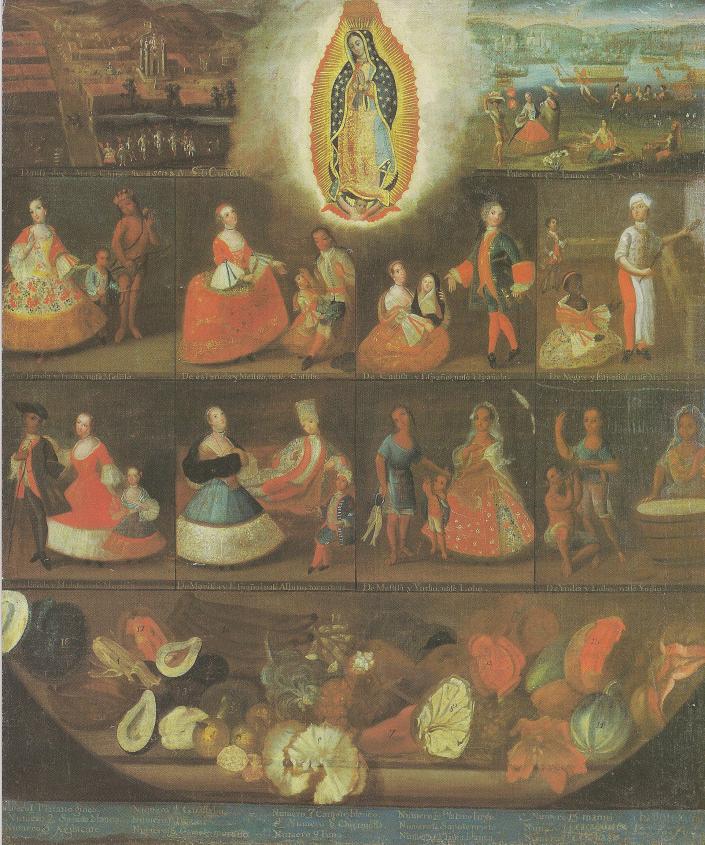

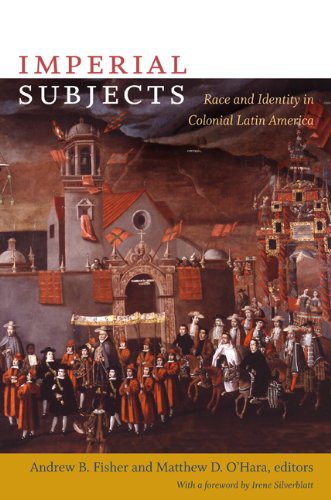

Cope overturned the idea that racial identity in colonial Mexico was “fixed permanently at birth” and argued that race was a versatile identity that could be “reaffirmed, modified, manipulated, or perhaps even rejected.” The unfixed nature of identities assumed and performed by individuals and groups in colonial Latin America beyond Mexico City is the subject of the collection of essays edited by Andrew Fisher and Matthew O’Hara recently published as Imperial Subjects: Race and Identity in Colonial Latin America.

Cope overturned the idea that racial identity in colonial Mexico was “fixed permanently at birth” and argued that race was a versatile identity that could be “reaffirmed, modified, manipulated, or perhaps even rejected.” The unfixed nature of identities assumed and performed by individuals and groups in colonial Latin America beyond Mexico City is the subject of the collection of essays edited by Andrew Fisher and Matthew O’Hara recently published as Imperial Subjects: Race and Identity in Colonial Latin America.

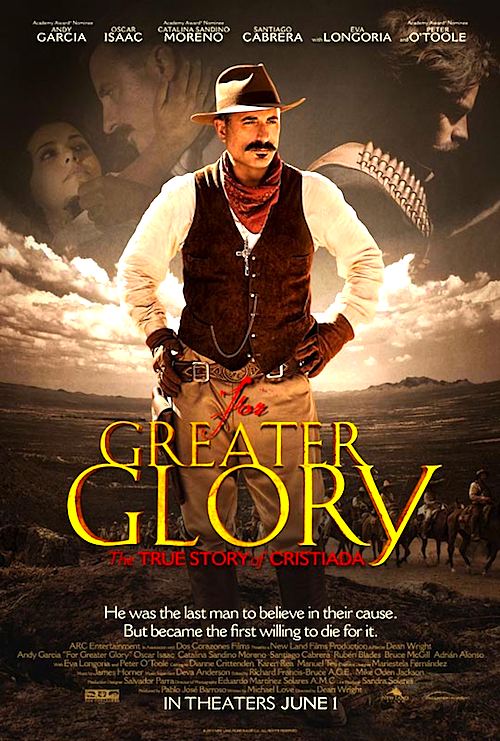

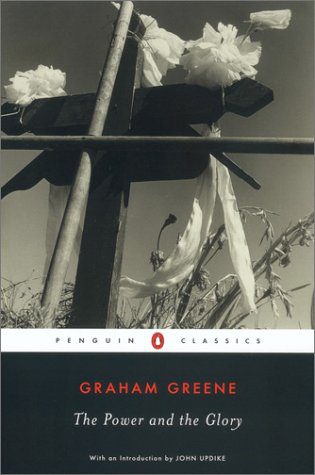

The Catholic Church at that time was under attack for its considerable wealth and social control. The unnamed priest at the center of the novel is a complicated man, by no means a conventional hero, but his refusal to abandon the priesthood eventually endows him with a magnetic aura of spirituality, despite his many vices.

The Catholic Church at that time was under attack for its considerable wealth and social control. The unnamed priest at the center of the novel is a complicated man, by no means a conventional hero, but his refusal to abandon the priesthood eventually endows him with a magnetic aura of spirituality, despite his many vices.