By Jimena Perry

(All photos are courtesy of the author.)

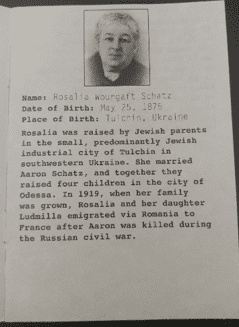

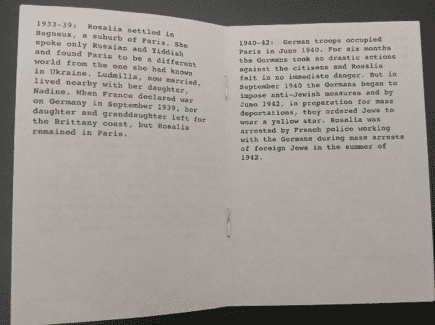

The only facts we know about Rosalia Wourgaft Schatz are that she was raised by Jewish parents in the city of Tulchin in southwestern Ukraine. In 1919 her family emigrated to France and in 1940 when the Germans occupied Paris and began their anti-Jewish politics, she, like many other Jews, was forced to wear the yellow star. In 1942 she was deported to Auschwitz where she was murdered at age 67.

Rosalia’s brief life story is registered in the Identification Card #1847, found at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, founded in 1983 in Washington, D.C. Her IC is one of thousands that can be find in a shelf near the venue’s second floor elevators, that take you up to the main floors of the permanent exhibit. Before starting the tour, visitors can take an identification card like Rosalia’s, to go through the display with an actual target of the Nazi regime in their hand. The idea is that every person who enters the exhibit will get to know at least one victim. The short biographical information found in these cards are the only data we will ever know of many of the casualties of the Nazis, aside from the fact that they were one of the approximately 6 million Jews killed during the Holocaust.

Once on the main exhibit floors, people can see the atrocities of the Nazi regime against Jewish, Roma, Armenian, and other minority populations. One of the main purposes of the curators of the United States Holocaust Museum is to encourage and promote the audience to keep asking “Why?” There is plenty of evidence of the torture and brutality committed by the Germans against their target populations but the basic question, why? still remains unanswered. The need to elucidate responses, find more explanations, and ignite further discussion fuels the intention of the museum professionals. This is evident at the very entrance to the building where vistors see two big posters that state: “This museum is not an answer but a question” and “What`s your question? #AskWhy”

As basic as these inquiries may seem and despite the myriad answers they have produced, there is something missing for the victims and their families. The basic Why? is still hovering in the back of the minds of those who endured and survived the Holocaust.

It is a question that the curators, employees, and researchers of the museum use to create historical memory narratives that include the victims, remember and honor them, and counteract versions that deny that these violent events did actually happen.

Raising awareness of the past to understand contemporary issues is one of the bridges built by memory museums because they demonstrate with facts, testimonies, documents, and images that atrocities like the Holocaust occur. In this sense, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum is considered a pioneer in display and representation of difficult topics. Another of the main objectives of the professional team of the museum is that the world will not allow the repetition of these brutalities. In the current political climate not only in the United States but in Latin America, for instance, where racism, discrimination, and exclusion are acquiring strength, to know that genocide is real and can happen is key. To deny or distort the Holocaust or other violent conflicts invalidates the victims’ voices, and prevents people like Rosalía and many others from finding justice.

This museum, as most memory sites, however, generates polemics. Should the past be relived in a setting like a museum? Do the survivors feel retraumatized by the displays? Is it not better to forget what happened? Apparently not since during the last decades there has been a huge proliferation of memory museums and displays, which demonstrates that diverse communities want to know what happened in order to restore the social fabric of their societies, to decide what to pass on to future generations, and to attempt to prevent atrocities from happening once more.

Other Articles You Might Like:

The End of the Lost Generation of World War I

The Radiance of France

The Museum of Sour Milk

Also by Jimena Perry:

More than Archives

Too Much Inclusion

My Cocaine Museum

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.