Interviewed by Amber Abbas

Alig Apartments, Shamshad Market, Aligarh (June 15, 2009)

Transcript:

Context Notes: I arrived at the home of S.M. Mehdi without an appointment, having been referred to him through a chance encounter with a University official. Though he was never a student of Aligarh, he has moved to the town after his daughter did her Medical degree there and is now practicing in Aligarh. S.M. Mehdi was surprised to see me, but agreed to answer my questions though he cautioned he could not be considered an expert on Aligarh. He told me, instead, of his experiences during partition as a Communist in Bombay. He worked for thirty years in the Soviet Embassy in New Delhi and has been a lifelong Communist. He is a very friendly and engaging person. He is tragically losing his vision and was eager for conversation. Though I met him only briefly, I felt very comfortable during my few visits to his home and looked forward to them.

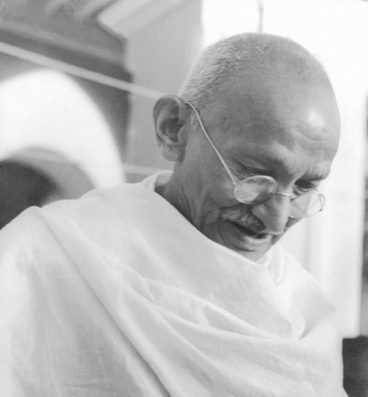

SMM: There is another interesting incident I will tell you about that period. That is in 1948 when Gandhi was killed. That particular day I was going to Bhopal from Bombay. Thre was a very, very good friend of mine, Munish Saxena, he said, “I will come with you to the station.” So, Sardar Jafri, the Urdu poet, was getting married that day. There was a reception and so we went to the reception and then Munish said, “Come along, let us go, because then your train will be—[going].” I said, “Alright.” So we went to take a taxi. As we went there, we saw some people engaged in rioting on the road. So I asked somebody, “What is happening?” He said, “Gandhi assassinated.”

I said, “No, this is impossible, this must be some work of RSS, this propaganda business, this is nonsense.” So we took a taxi and we went to Victoria Terminus- have you been to Bombay?

AA: No.

SMM: Victoria Terminus was the name, now it is of course, changed [to] something else. So Victoria Terminus is a huge railway station! Very old! During British time it was made. And of course it was busiest area of Bombay. So we took a taxi, I had a small suitcase with me. We went to the station. And as we reached the station it was confirmed that Gandhi was killed, assassinated that time. So Munish told me, “Mehdi, if a Muslim has killed Gandhi, then there is going to be large scale trouble and I don’t think you should go because you’ll be in danger.” I said, “Yes, you are correct. So what do we do?” He said, “Let us go back and then see what happens. Who killed Gandhi, first of all?” I said, “Alright.” So I put my suitcase in the cloakroom and said, “Alright, go.” And can you believe me? As we came out of the railway station with buses and trams and taxis and whatnot and private cars, etc. I mean, Bombay! A city like Bombay, and especially that railway station! My God, what a huge thing it used to be.

And as we came out, there was nothing! Absolutely nothing on the road! No trams. No bus. No taxi. No car. Even no person! No man! Oh God, what has happened! Within two minutes, what happened? The whole city is dead! It was eerie. Terrible. What do we do now? No taxi available and miles and miles we have to go to reach where we were staying in Walkeshwar Road near Malabar Hill. So Munish said, “Let us try the local train and let us go from here, walk down to the railway station, the local train station.” I said, “Alright.” So I and Munish walked down. My God! There was no train. There were no passengers! The whole platform was deserted.

Oh God. It was such a—what do we do now? I said, “What can we do? Let us walk.” We started walking. And, I mean, there was no alternative. There was no train, there was no taxi, there no bus, that’s why. I mean, there was no person on the road! My God. So we were walking, and by this time it was sunset and it was dark now, because we were walking and walking and walking. We saw some light coming from behind us. So I thought it might be a taxi so I flagged it. As it stopped, I came to know that it was a [private] car and it was driven by a Sardarji, Sikh. He was all alone in his car.

We said, “I’m sorry, I thought it was a taxi.” He said, “My dear, there is no taxi today. Where are you going?” I said, “Na, na, na. It is alright, we are just going.” He said, “Look, today you cannot have anything so please come and sit in my car and I will reach you there.” So I looked at Munish, and Munish looked at me. He said, “Alright, baitiye. (sit)”

AA: Did you feel a little bit—?

SMM: Dar lag rahe hain ke patha nehin, Sardarji kaun? Kya kar dein?

(It was frightening, we didn’t know who this Sardarji was. What would he do?)

AA: Aur abhi tak aapko nehin maloom tha ki Mussalman nehin tha? Jinhone mara?

(Up till now you didn’t know that it wasn’t a Muslim? Who killed him?)

SMM: Nehin, nehin. Abhi kuch nehin patha! (No, no. We didn’t know anything!) Tho Sardar asked us, “Where are you going? Which locality?” We didn’t want to give him the name of the locality that we are living in Walkeshwar Road. We said, “No, no, Sardaji, you just please drop us at Opera House.” Opera House was a place, from there we could take a bus to our house. He said, “Alright.” We asked him, “Sardarji, where are you going?” He said, “I am going to Pakistan. And come along, you also come with us!” Meaning: Muslim areas. He was going to kill. So we laughed, and said, “No, no, we have got some work to do, etc. etc. So please you drop us near the Opera House. He said, “Alright.” So he dropped us and he went away.

So we walked and reached our house where Sardar Jafri and his newlywed wife were there. They asked us, “What is this?” So we told them the whole story about it. So he said, “How do we know who has done it?” By that time, it was nine o’clock in the night. There used to be a nine o’clock new bulletin everyday. That was an important news bulletin of the radio. So he said, Sardar Jafri told me, “See, on the ground floor, there is a lady, a Muslim lady, a Khoja, who stays there. If you go to her maybe she will allow you to listen to the news on the radio.” So I went there. There was only one woman living in this huge flat, it was quite a big flat. So I told her and she said, “Hanh, hanh. Yes, please go ahead and listen.” She did not know anything in the world what is happening whether Gandhi is dead or alive. She didn’t know anything!

So I just opened her radio for the nine o’clock news and Sardar Patel came out that “A Fanatic Hindu has killed Gandhi.” Oh, God. I felt so relieved! (laughs) So it was the next day that I took the train for Bhopal. (laughs)

AA: How did it strike you, emotionally, that he had been assassinated?

SMM: Hhmm? How did I?

AA: How did you feel, emotionally?

SMM: Oh, emotionally, about Gandhi. Hanh, hanh. Emotionally, about Gandhi I thought, I mean, we thought less, I suppose, than ourselves. What is going to happen to us? Presuming some one is going to stab us, kill us. Who has killed? The whole thing was, who can it be? And it always came down, it must be a Muslim, it might be a Muslim, it must be a Muslim, it might be a Muslim, that’s all. It must be a Muslim. We thought that Muslim Leaguer must have killed Gandhi. Because at that time they were saying that partition is not in favor of Pakistan but is in favor of—the Radcliffe Award is in favor of India, not Pakistan.

So, yeh dimag me baj gaya raha tha ke “Kis ne mara hoga? Mussalman hi ho sakta jisne mara hoga.” (This was bouncing in the mind that, “Who will have killed him? It could only be a Muslim who will have killed him.”) It must be a Muslim who has killed. And we were looking bhai, ke koi aa na raha ho, koi dekh na raha ho, koi marna nehin hum logon ko. (And we were looking, man, that no one should be coming, no one should be watching, no one should kill us.) And as we heard this news that a fanatic Hindu has killed Gandhi, it was a really greatly—I mean, just imagine! We, who did not believe in this nonsense of Hindus and Muslims, when we heard that a Hindu had killed Gandhi, we felt relieved. That at least a Muslim has not killed Gandhi. That was a terrible experience of my life.

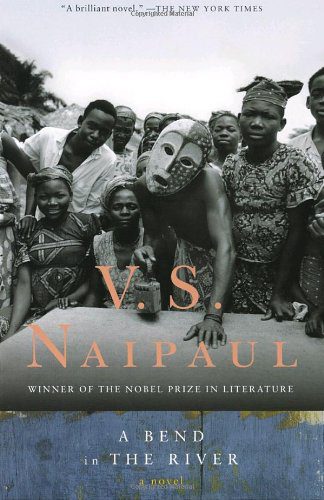

Much like its eponymous waterway, V.S. Naipaul’s A Bend in the River meanders steadily through the dark reality of postcolonial Africa, alternately depicting minimalist beauty and frightening tension. Like Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, subtle prose reveals the timelessness of the continent’s remote corners alongside human corruptibility. Yet, Naipaul moves his narrative closer in time to contemporary Africa, demonstrating that the horrifying legacies of colonialism did not end with Europe’s retreat. In A Bend in the River, the struggle to establish national identities in the wake of Western imperialism takes center stage, with “black men assuming the lies of white men” in order to govern.

Much like its eponymous waterway, V.S. Naipaul’s A Bend in the River meanders steadily through the dark reality of postcolonial Africa, alternately depicting minimalist beauty and frightening tension. Like Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, subtle prose reveals the timelessness of the continent’s remote corners alongside human corruptibility. Yet, Naipaul moves his narrative closer in time to contemporary Africa, demonstrating that the horrifying legacies of colonialism did not end with Europe’s retreat. In A Bend in the River, the struggle to establish national identities in the wake of Western imperialism takes center stage, with “black men assuming the lies of white men” in order to govern.