Ahnia Leary

Pin Oak Middle School

Junior Division

Individual Performance

Treme is one of the most iconic neighborhoods in New Orleans. Its dynamic history, culture and music even inspired a critically acclaimed HBO drama. Ahnia Leary wanted to present the story of this vibrant section of the Big Easy for Texas History Day, particularly its long history of racial tension and black activism. Her performance uses jazz music to capture the diverse people, places and stories that make up Treme.

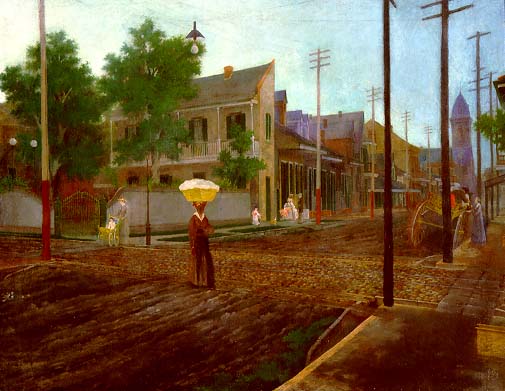

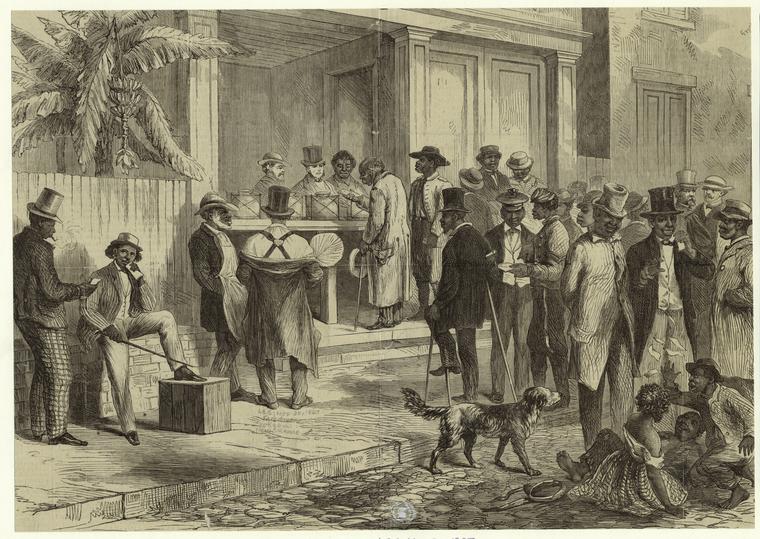

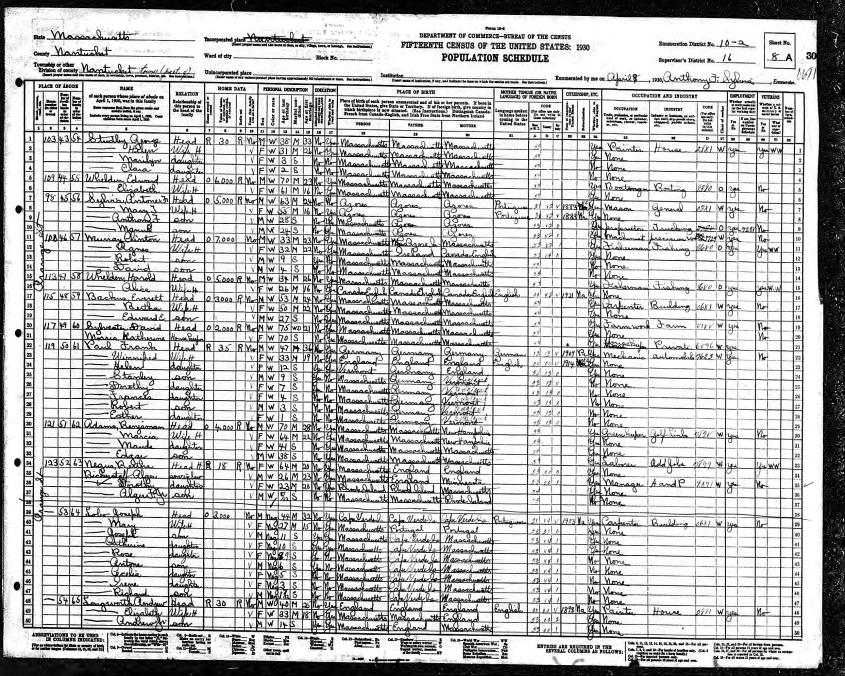

After viewing the documentary, Fauberg Treme: The Untold Story of Black New Orleans, I was both excited and intrigued by the fact that there were Free People of Color in New Orleans who in the 1800s, owned about 80% of the land in the Treme community. Under French and Spanish rule, slaves (primarily from Senegal and Senegambia) could also work to buy their freedom. This unique suburb also included Europeans from many Countries as well as free people from St. Dominigue (Haiti) . My curiosity peaked and I was inspired to find out more about Homer Plessy and the Comite des Citoyens (Citizens Committee) which included writers, business owners, newspaper editors and activists who fought to ensure their right to be free of Jim Crow laws. My interest in the topic increased as I wondered why this history is unknown, the reason for racial hatred and what can be done to get rid of it and heal the past.

The Performance category was chosen because it offers a creative way to present my research. My script was developed using primary source material (translations) and information from historians and interviews. I also prepared a short piano piece with the help of my piano teacher, Olga Marek, providing an example of Spanish influence to early jazz music inspiring Jelly Roll Morton, who lived in Treme.

Finally, the National History Day Theme is: Rights and Responsibilities in History. Free People of Color like Captain Arnold Bertonneau, Paul Trevigne, Homer Plessy and others exhibited extreme courage and personal responsibility in their fight for the rights of people of African descent, to participate fully in America as citizens, living its dream and demanding Color blind justice.

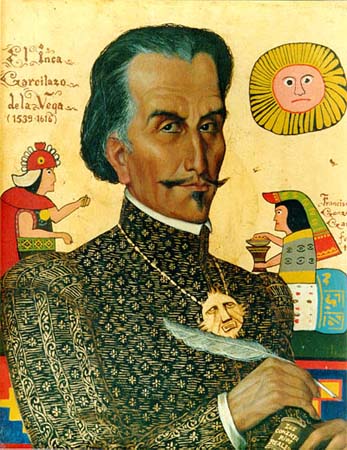

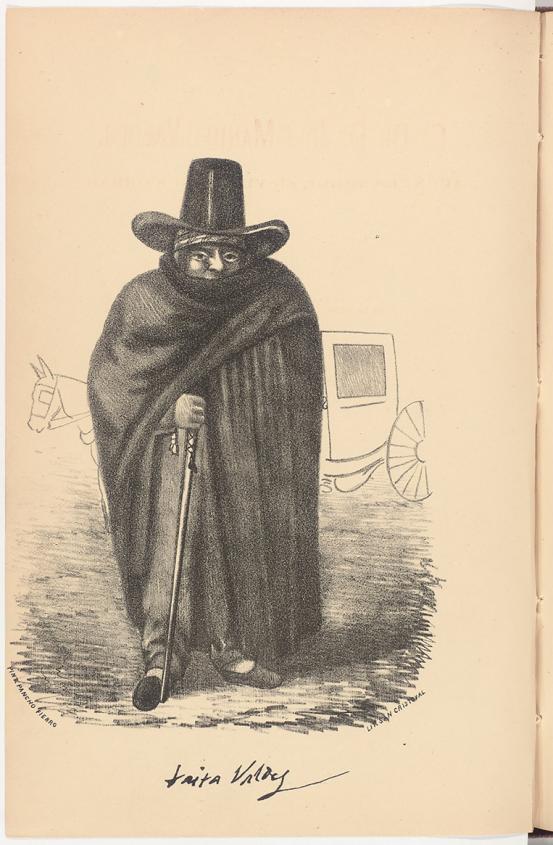

Cope overturned the idea that racial identity in colonial Mexico was “fixed permanently at birth” and argued that race was a versatile identity that could be “reaffirmed, modified, manipulated, or perhaps even rejected.” The unfixed nature of identities assumed and performed by individuals and groups in colonial Latin America beyond Mexico City is the subject of the collection of essays edited by Andrew Fisher and Matthew O’Hara recently published as Imperial Subjects: Race and Identity in Colonial Latin America.

Cope overturned the idea that racial identity in colonial Mexico was “fixed permanently at birth” and argued that race was a versatile identity that could be “reaffirmed, modified, manipulated, or perhaps even rejected.” The unfixed nature of identities assumed and performed by individuals and groups in colonial Latin America beyond Mexico City is the subject of the collection of essays edited by Andrew Fisher and Matthew O’Hara recently published as Imperial Subjects: Race and Identity in Colonial Latin America.