Nineteen-year-old Antonio de Ulloa set sail for the Americas in the spring of 1735. Ulloa was traveling as one of two assistants to a contingency of French scientists appointed to South America. The observations Ulloa and his counterpart, Jorge Juan, made on the excursion culminated in Relación Histórica del Viage a la America Meridional. The Relación Histórica is a five-volume work published in 1748 that provides in-depth cultural descriptions of the Spanish colonies’ major cities. As a traveler’s account, Relación Histórica made the colonies accessible for the considerable literate Spanish population who knew little of the empire’s overseas territories. For contemporary readers, it proves fundamental to understanding the socio-racial caste hierarchy that defined the colonies.

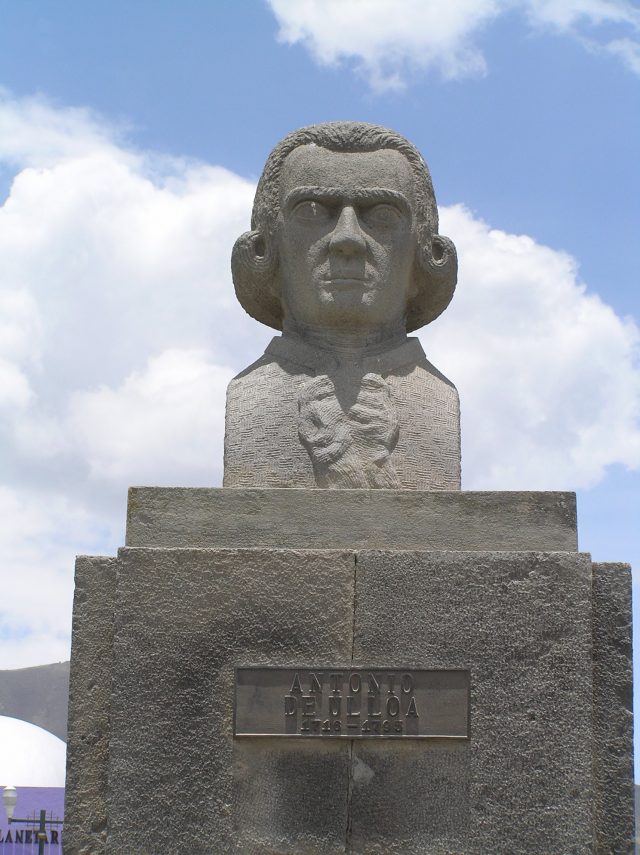

Antonio de Ulloa y de la Torre-Giral became a general of the navy and a colonial administrator. He was later the first Spanish governor of Louisiana (via Wikimedia Commons).

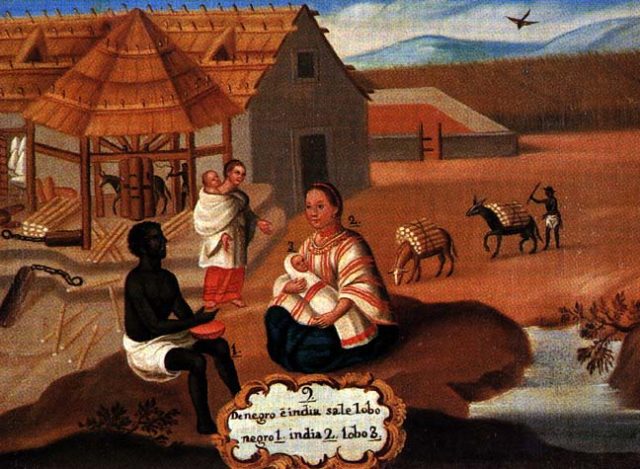

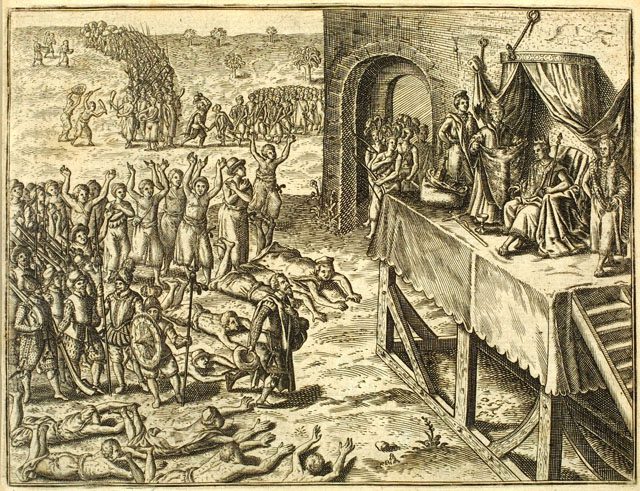

By the eighteenth century, Spanish colonial society comprised a diverse socio-racial landscape. Intermarriage and sexual unions among Indigenous, African, and Spanish populations produced a society that could not easily be categorized according to conventional European social and economic privileges. Establishing a sociedad de castas (caste society), elite Spaniards recognized upwards of twenty racial castes with behavioral qualities unique to each group. Implementing the hierarchy relied primarily on public forms of social control, such as the prohibition of certain castes from administrative and commercial positions and laws that excluded certain fashions from non-Spanish castes. Colonial elites, however, faced challenges in enforcing strict racial stratification, and, as Ann Twinam has shown, loopholes broke down the efficacy of the racial hierarchy. Traveler’s accounts of the Spanish colonies offer key outside perspectives on these inconsistencies that allow us to evaluate how deeply socio-racial limitations permeated through colonial society.

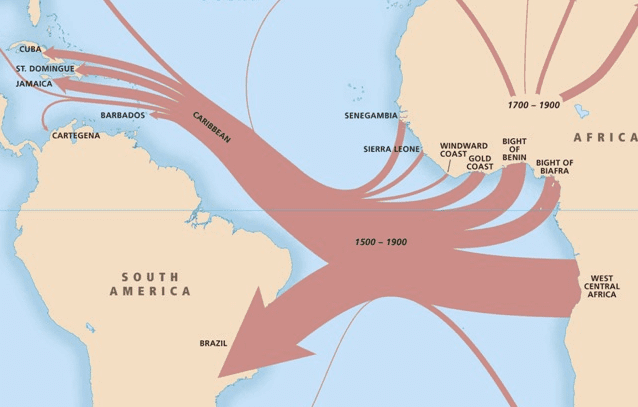

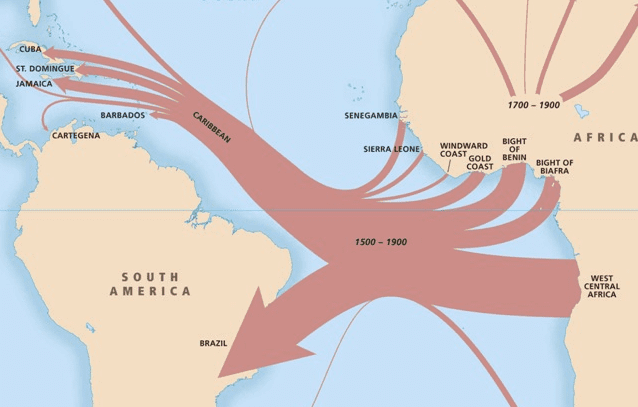

Antonio de Ulloa’s fifth chapter, “Understanding the People of Quito; the Castes Found; Their Customs, and Riches” addresses the realities of implementing the caste system in a complex urban environment. Immediately, Ulloa asserts a high level of stratification found within society, noting that noble families “have kept themselves in their luster, connecting themselves with each other and not mixing with the people of low birth.” Ulloa further defines “low birth,” describing “four classes: that are Spanish, or whites; mestizos; Indians, or Naturals; and Blacks with their descendants” (363). While Ulloa’s racial classification affirms the presence of racial separation, the description of only four racial castes points to larger questions of the racial demography found in Peru. Ulloa presents Africans as a distinct group in society, but they are “not as abundant, as in other places in the Indies,” suggesting that Quito did not rely as heavily on African slave labor as perhaps other colonial cities.

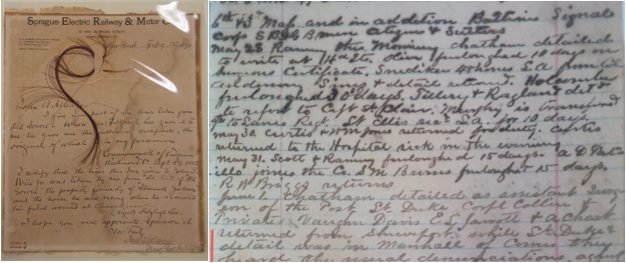

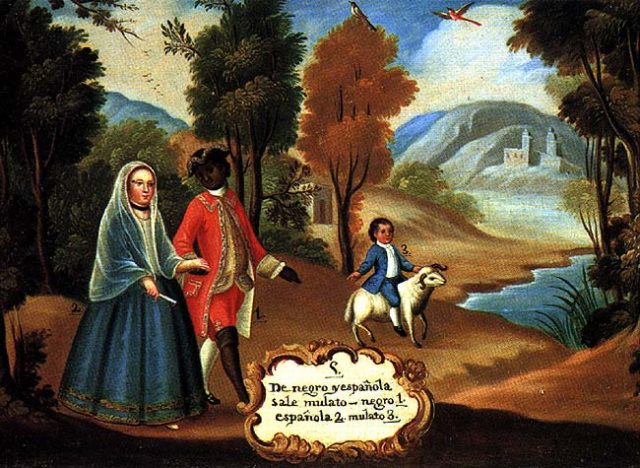

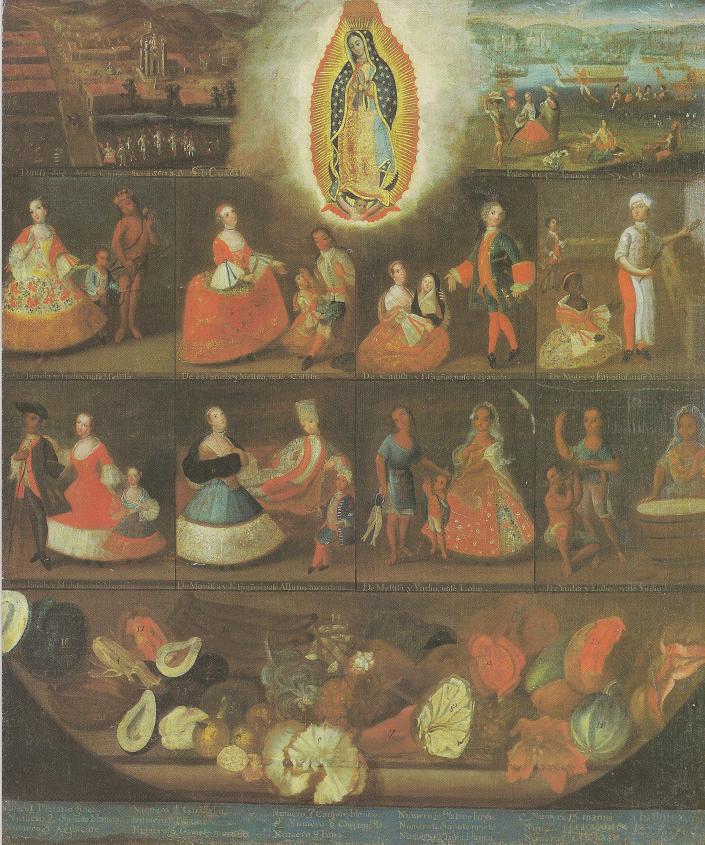

A casta painting from ca. 1770. It depicts a Spanish father and an indigenous mother with their mestizo baby (via Wikimedia Commons).

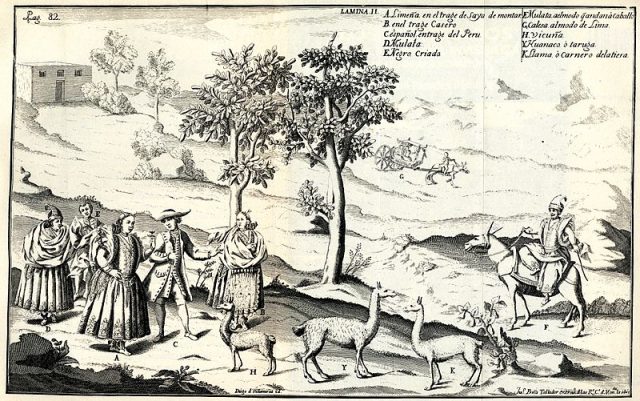

Ulloa deepens his discussion of the socio-racial dynamic found in Quito by describing stereotypical behavior associated with the most prominent racial groups. Ironically, he condemns Spaniards as “the most unhappy, poor, and miserable; because the men do not apply themselves to any business” due to their superior racial quality (365). He praises mestizos who “work with perfection,” but ultimately fall prey to “the defect of Laziness and sloth, of which dominates them strongly” (365). These observations of work ethic mimic popular conceptions of how race influenced personality and behavior. Finally, Ulloa evaluates the visual appearance of Quito’s inhabitants, claiming, “people dress ostentatiously; and fabrics of gold, silver, fine scarves, and other types of silk and wool are not uncommon” (366).

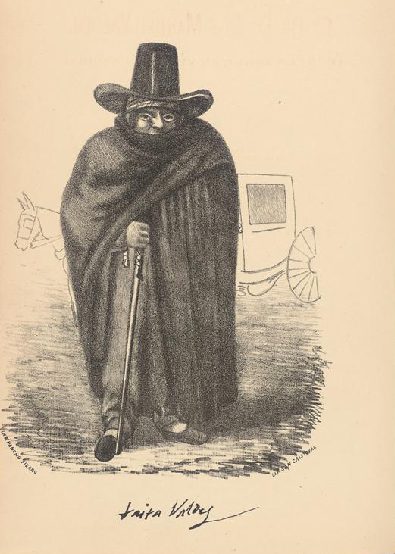

An illustration from Relación Histórica del Viage a la America Meridional of the peripheral countryside of Peru (via Wikimedia Commons).

Ulloa’s account also addresses larger questions concerning the conceptualization of race in both colonial and peninsular Spanish society. His depiction relies heavily on exterior evaluations of race, such as status, behavior, and appearance, suggesting that society largely defined racial classification through overt visual markers. Ulloa’s description demonstrates that implementation of the racial caste system had some influence in Quito. For example, according to Ulloa, mestizos frequently worked in artisanal occupations such as “painters, sculptors, silversmiths, and others,” demonstrating a sense of racial occupational organization (365). He reinforces ideas being produced within the Spanish colonies by proving that racial stratification was clearly noticeable to foreigners.

Despite confirming widespread stratification in daily society, Ulloa’s account proves even more valuable for the inconsistencies that it records. He writes that, “many mestizos appear to be of the same color as legitimate Spaniards, being white, and blonde; and they are considered as such, even though in reality they are not.” (353) In this one brief sentence, Ulloa recognizes a fundamental weakness in the socio-racial hierarchy. Despite the creation of at least twenty racial castes in society, ambiguous physical markers allowed some social mobility along the racial spectrum. Mestizos with European complexions could sometimes assimilate into the Spanish demographic, which undermined the rigidity of the caste system.

Traveler accounts such as Ulloa’s are useful to historians in determining how colonial society presented itself to foreigners, but authors of such accounts carried preconceived notions of the Spanish colonies. Ulloa’s account inherently reflects peninsular prejudices and preconceptions of the colonies. Historians must determine to what extent Ulloa imposed peninsular ideologies upon the colonial social structure. As an outsider, for example, since Ulloa most likely only gained access to public society, he can demonstrate the racial stratification seen in public but cannot speak to the intimate realities that occurred in private.

Antonio de Ulloa’s analysis of Quito’s residents exists within a broader attempt to categorize and identify the unique racial make-up of the Spanish colonies. Colonial society continuously tried to grapple with its own racial ambiguity, often relying on public campaigns like casta paintings that depicted mixed race families and the racial variety of the caste society and whitening decrees that attempted to regulated social structures. However, travelers’ accounts like that of Ulloa offer an outsider’s perspective to the multi-colored reality. Answering key historical questions about race in Peruvian society while raising further inquiries into the realistic validity of the caste system, Relación Histórica del Viage a la America Meridional places modern readers in the thick of colonial Quito society.

![]()

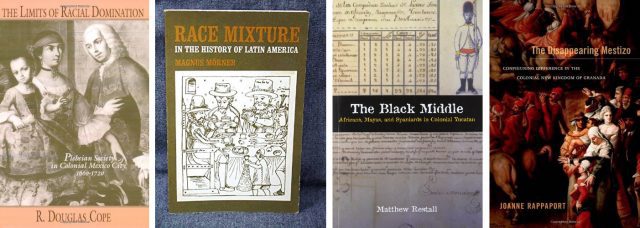

Sources for this article and for further reading:

Magli M. Carrera, Imagining Identity in New Spain: Race, Lineage, and the Colonial Body in Portraiture and Casta Paintings. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2003.

Jorge Juan and Antonio de Ulloa, Relación Histórica del Viage a la America Meridional. Madrid: 1748. The Nettie Lee Benson Latin American Collection Rare Books and Manuscripts Division, University of Texas Libraries.

Irving A. Leonard, Introduction to A Voyage to South America, by Jorge Juan and Antonio de Ulloa. Translated and Abridged by John Adams. Tempe: Arizona State University, 1975.

Ann Twinam, Purchasing Whiteness: Pardos, Mulattos, and the Quest for Social Mobility in the Spanish Indies. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2015.

You may also like:

Ann Twinam disucssers her book Purchasing Whiteness: Race and Status in Colonial Latin America.

Susan Deans-Smith explains how casta paintings described the racial hierarchy of Colonial Latin America.

Adrian Masters reviews The Disappearing Mestizo, by Joanne Rappaport (2014).

![]()