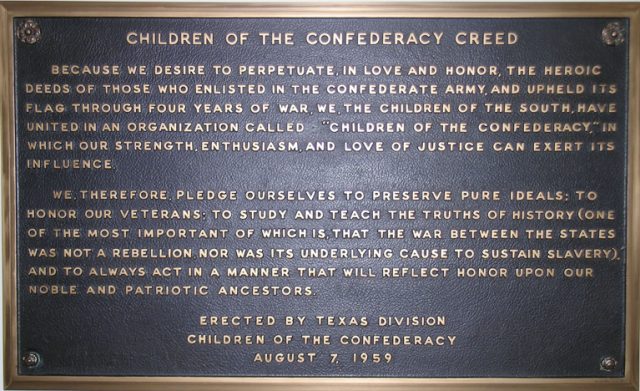

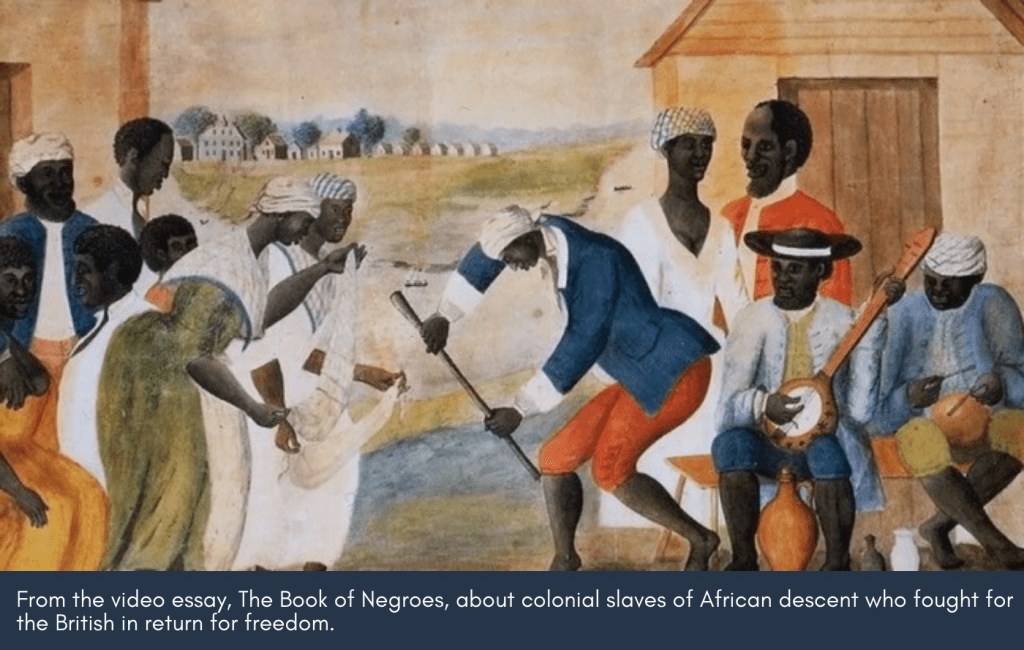

Ibram X. Kendi’s magnum opus, Stamped from the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America, is a transformative work that transcends traditional scholarship to provide a profound examination of the roots and manifestations of racism in the United States. Published at a critical juncture in history–marked by both symbolic progress and persistent racial challenges–Kendi’s groundbreaking narrative dissects the historical development of racist ideas. As the nation grappled with the paradox of having its first African American president during the final years of Barack Obama‘s presidency, the book emerged against a backdrop of heightened awareness of racial injustice, debates about Confederate symbols, and the rise of white nationalist ideologies. Ibram X. Kendi’s exploration of the historical roots of racism provided a timely lens through which to understand and address contemporary racial issues during this pivotal period. In addition, it offers an invaluable lens through which contemporary policymakers can confront and dismantle systemic inequities. As a historian and scholar of race and discrimination in America, Kendi takes readers through the annals of American history and reveals the insidious evolution of racist ideologies from their inception to the present day.

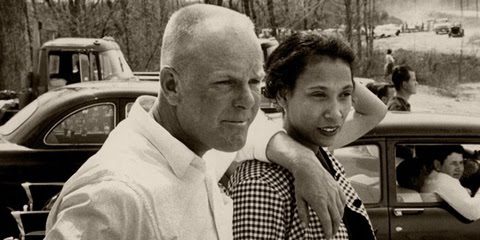

Source: Library of Congress

At its core, Kendi’s work challenges the conventional wisdom regarding the roots of systemic racism. While the prevailing perspective often centers on individual attitudes and actions as the primary drivers of racial disparities, Kendi posits that racist ideas have historically been intertwined with policies. Thus, Kendi challenges simplistic categorizations and encourages a more comprehensive understanding of the historical development of racist ideologies. The essence of Kendi’s work lies in its commitment to truth-telling. He urges readers to acknowledge the historical context that has fueled the persistence of discriminatory policies, encouraging a paradigm shift from mere acknowledgment to proactive dismantling. Stamped from the Beginning is not merely a historical scholarship; it is a call to action that prompts policymakers to scrutinize their beliefs and assumptions, fostering a critical examination of the systems they construct and maintain.

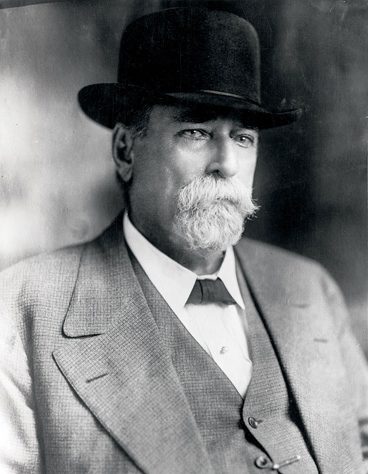

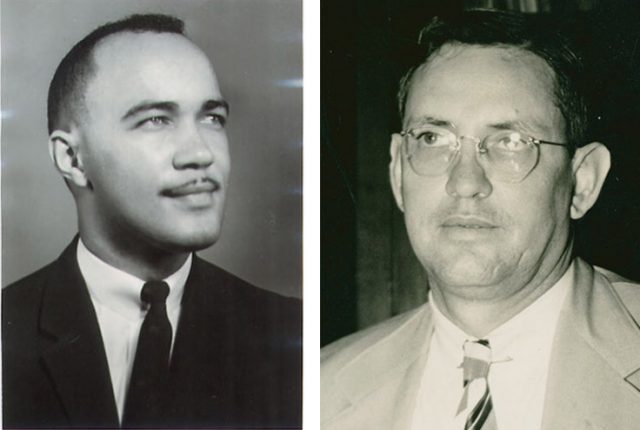

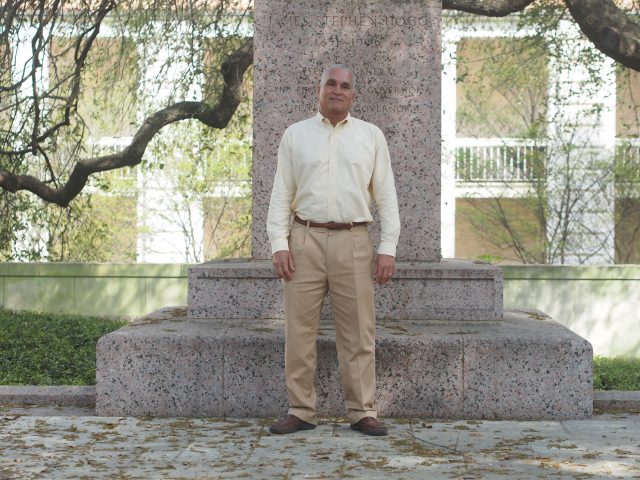

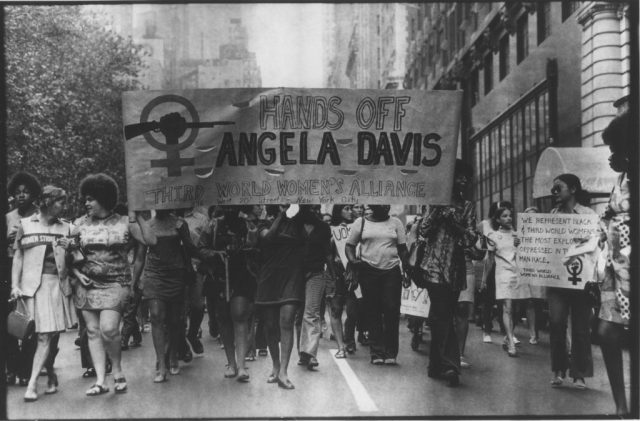

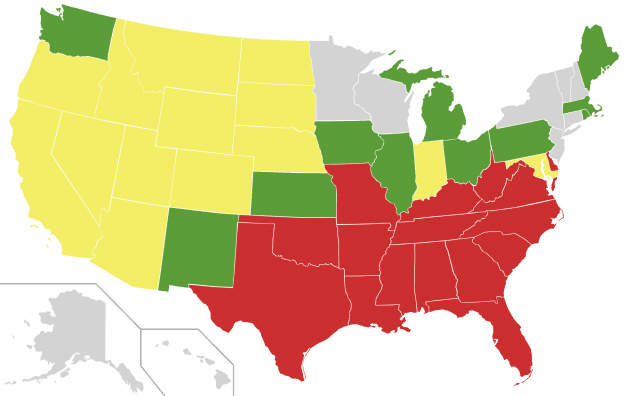

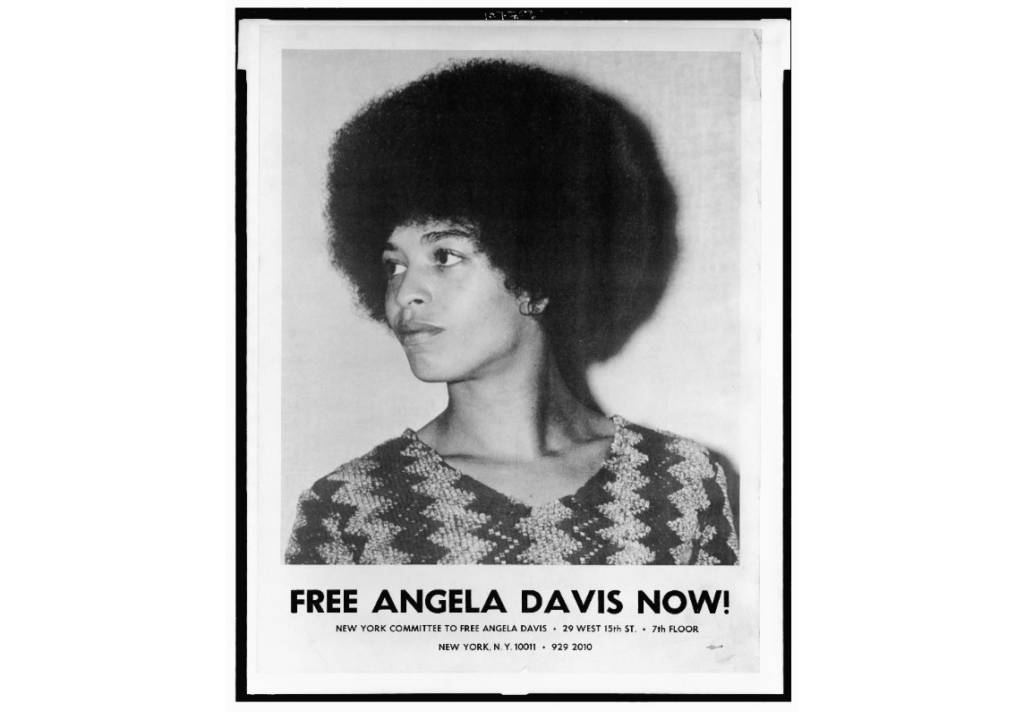

Kendi’s theory shifts the conventional paradigm in the discourse on racism. He argues that racism is not solely a product of individual attitudes but is deeply embedded in the policies and structures of society. Kendi’s comprehensive exploration revolves around the lives and beliefs of five key historical figures representing different periods in American history. These figures, including Cotton Mather, Thomas Jefferson, William Lloyd Garrison, W.E.B. Du Bois, and Angela Davis, offer a spectrum of perspectives on race, illustrating the multifaceted nature of racism and how it became ingrained in societal structures and policies. By doing so, Kendi challenges the prevailing notion that racism is merely a collection of isolated incidents or prejudiced beliefs. Considering racism’s persistence, Kendi suggests shifting our focus toward policies and institutional structures. The book also challenges the binary framework that often separates individuals into “racist” or “not racist” categories. Kendi proposes a spectrum of racism, introducing the terms “segregationist,” “assimilationist,” and “antiracist” to describe different approaches and beliefs regarding race. This nuanced framework encourages readers to reflect on their own positions on this spectrum and consider the broader implications of their ideas within the context of systemic change.

Source: Library of Congress

The book’s relevance extends beyond historical analysis, making it an essential read for anyone seeking a deeper understanding of the ongoing struggle against racism in the United States. Stamped from the Beginning emerged at a critical period in American history during the latter years of Barack Obama’s presidency. Published in 2016, the book entered the literary scene amid a nation grappling with the paradox of celebrating its first African American president while confronting enduring racial inequality. Kendi’s work engaged with contemporary challenges and provided historical context to elucidate their origins, becoming a crucial resource for those seeking to comprehend the historical racial injustice continuum underpinning present-day struggles.

Stamped from the Beginning is exceptionally accessible, employing a narrative style that makes it understandable to a diverse audience. Kendi sidesteps unnecessary jargon, ensuring that the material remains open to different readers. The book’s rigorous approach and original research draw on various primary and secondary sources, contributing to new insights into understanding racist ideas and their policy impact through a historical rhetorical analysis of speeches and correspondences. While the use of Kendi’s specific individual case studies–Mather, Jefferson, Garrison, Du Bois, and Angela Davis–provides powerful case studies and allows for a nuanced exploration of racism, I argue that this approach is limiting.

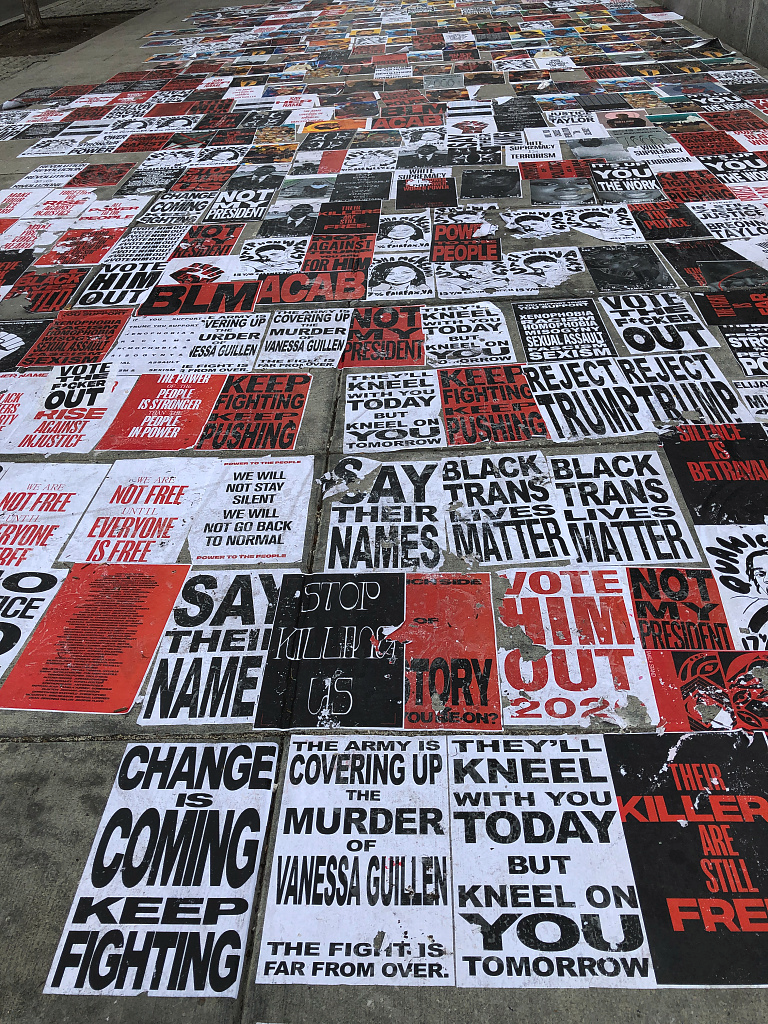

The concern here is that by centering the narrative primarily on the lives and beliefs of specific individuals, the book risks overlooking or underemphasizing broader collective societal attitudes and actions. Racism is not solely the product of a few influential individuals but is often deeply ingrained in the structures and norms of a society. A more expansive examination of collective forces, social movements, and systemic influences would provide a more holistic understanding of how racist ideas permeate and persist in society. I argue that if Kendi explored the influence of institutions, cultural norms, and widespread attitudes alongside individual narratives, he could have provided a more complete picture of the complex interplay between racism and society, which is one of the main arguments he makes throughout the book.

Source: Library of Congress

While the book effectively demonstrates how individual actions contribute to the perpetuation of racist ideologies, it may leave some readers wanting a more comprehensive analysis of the broader societal context in which these individuals operate. Exploring the influence of institutions, cultural norms, and widespread attitudes alongside individual narratives could provide a more complete picture of the complex interplay between racism and society. While the book successfully highlights the role of specific historical figures in shaping racist ideas, a broader examination of the social and institutional forces that contribute to the perpetuation of racism could enhance the reader’s understanding. Regardless, Stamped from the Beginning is a beacon in public policy literature, accessible and engaging yet deeply rooted in original research. It introduces a transformative theory that prioritizes policies in the fight against racism, challenges conventional paradigms, and encourages further exploration within the field. As a result, the book becomes a pivotal cornerstone in reshaping the discourse on race. It should be considered a canonical work in public policy for its transformative potential and paradigm-shifting insights.

Maddie (Williams) Shorman is a doctoral student in the LBJ School for Public Affairs at the University of Texas at Austin. Her doctoral research focuses on the transnational networks of religious nationalism. She is currently using network and content analysis to map church-state relations regarding views on violence from the pre-Constantine times to the modern era.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.