During the last two weeks, while researching my dissertation on Crimean Tatars in the National Archives of the Russian Federation, some of the people in my documents, such as Tatar leader Mustafa Dzmeliev, started appearing in news stories. Many historical accounts of events in the Crimea simply mention that Nikita Khrushchev “gifted” the Crimea to Ukraine in 1954. This does little to explain Crimea’s current demographic makeup or what happened to put the strategic peninsula in the position to be “given” by Moscow to Ukraine in 1954.

In fact, the transfer was the last in a series of actions concerning the peninsula carried out over several centuries by the Russian Empire and then the Soviet Union. While Crimea has a long independent history going back to Greek times, it was ruled by Crimean Tatars as members of the Golden Horde beginning in the 13th century and then the Crimean Khanate beginning in the early 15th century. The Khanate maintained a diverse merchant population, but this trade included raiding Russian villages and declaring sovereignty to the Ottoman Sultan. In 1774, Catherine the Great invaded Crimea to deter Ottoman control and, in 1783, annexed the peninsula and encouraged Russian and Ukrainian settlers to migrate to the Crimean coast. At the same time, tens of thousands of Crimean Tatars were deported to the Ottoman Empire.

In the mid-nineteenth century, the Crimean War (1853-56) brought another round of ethnic cleansing of Crimean Tatars, and many fled to Tatar communities in Turkey. Despite repressions, throughout Russian imperial history, most Crimean Tatars remained in Crimea. One consequence of state coercion against Tatars was that a Crimean Tatar, Ismail Bey Gasprinskii, began the Jadid Muslim reform movement that sought more modern schooling and the use of local languages written in Arabic script. Jadids such as Gasprinskii did not reject everything Russian but concluded that only a modernized and educated Tatar population in Crimea could protect itself from total Russification. Russian central government allowed Crimean Tatars to staff local positions in the imperial Islamic bureaucracy giving them control over education, religious instruction, and some policing and legal functions.

When the Tsarist regime collapsed in 1917, many Jadids helped form a short-lived revolutionary government, but the anti-Bolshevik White General Wrangel and his army ended Tatar’s attempts at governance by occupying Crimea. Some Jadids joined the Bolsheviks to defeat the Whites, as some Muslims did in the Lower Volga and Central Asia. The new Soviet government compromised with these Crimean Tatars and declared the formation of the Crimean ASSR, where both Russian and Tatar were official languages and local national Soviets oversaw the needs of Russians, Tatars, Ukrainians, and smaller minorities. Radical Jadids now became the direct beneficiaries of a Soviet nationalities policy that promoted indigenous ethnic nationalities, and they formed the political core of the Crimean ASSR during its “golden years” from 1923 to 1928. Even after the Stalinist terror in the 1930s, Crimean Tatars controlled much of the Republic’s government.

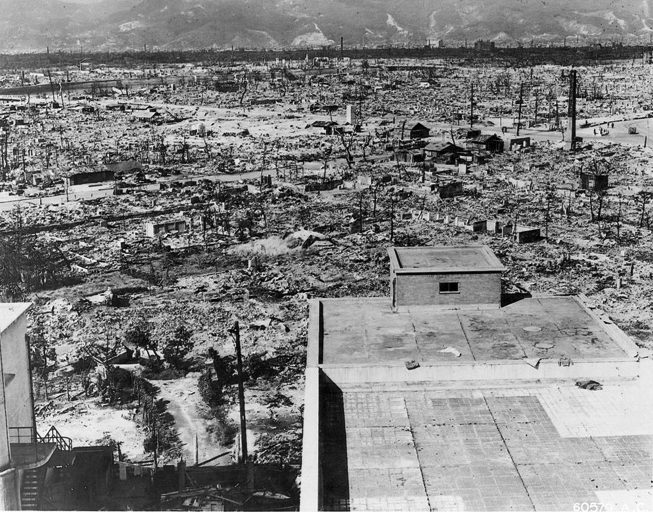

After the Nazi occupation and Soviet liberation of Crimea in 1944, however, Stalin deported the Crimean Tatars to Central Asia for allegedly collaborating with the Nazis. Although it is true that some Crimean Tatars did collaborate, recent scholarship has shown that Tatar treason was no more prevalent than that of any other nationality, including Ukrainians and Russians. Most of the male deportees had fought against the Nazis. More likely, Stalin’s motive in deporting the Crimean Tatars mirrored the fears of his Tsarist predecessors during the Crimean War: the Crimean Tatars were a “fifth column” due to the large diaspora in Turkey, and Sevastopol’s Black Sea Fleet was too important to Soviet strategy to risk.

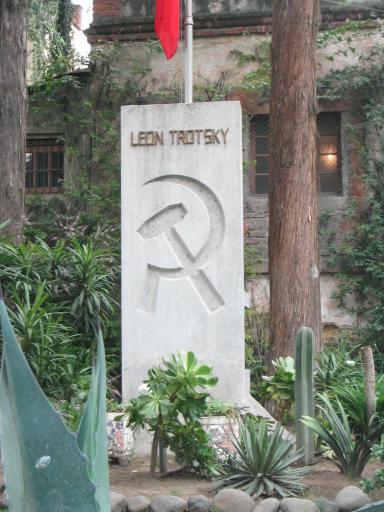

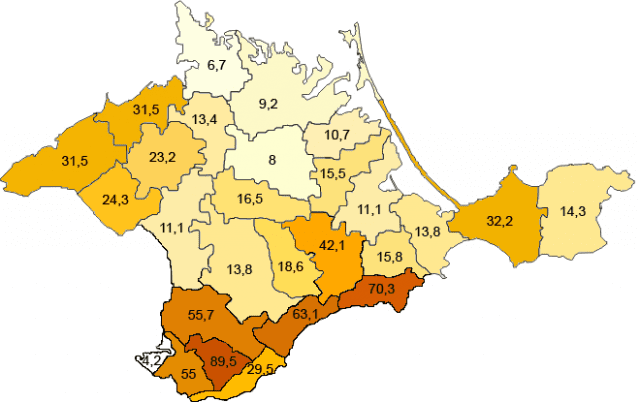

This mass deportation of Crimean Tatars, and not Khrushchev’s gift of the Crimea to the Ukrainian SSR in 1954, was the most important action taken by Moscow in determining the current demographic and geopolitical situation in Crimea. KGB officials quickly deported the entire population of Crimean Tatars (over 200,000 people) to Central Asia in May 1944. During the process, over 40% of Crimean Tatars perished as a result of horrible transit conditions and starvation once they arrived in Central Asia. On June 30, 1945, another order from Moscow liquidated the Crimean ASSR, and the territory became the Crimean Oblast, which is officially now part of the Russian RSFSR. At the same time, KGB and non-Tatar Crimean authorities removed all signs of Tatar life, while state media painted the Tatars as traitors. So when Khrushchev “gave” the Crimea to the Ukrainian SSR, just a year after Stalin died, on February 19, 1954, historical documents show that the demographic situation and the autonomy of local populations had already been greatly altered.

More orders concerning the Crimea following Stalin’s death are equally relevant. Crimean Tatars were one of dozens of Soviet nationalities deported during World War II, but many of the other deported nationalities such as Chechens and Ingushetians saw their autonomous republics reestablished by order of the Kremlin on January 9, 1957. The only large nationalities prohibited from rehabilitation were Crimean Tatars and Volga Germans. An order by Kliment Voroshilov on April 28, 1956 did absolve Crimean Tatars of being traitors and did allow Tatars to move outside of Central Asia, but did not allow them to return to the Crimea or reclaim confiscated property. While the refusal of the Soviet state to reestablish the Crimean ASSR may seem like a technicality, it is very important today. In other autonomous or Soviet Socialist Republics where indigenous ethnic groups remained in control of some governance, national groups have either gained independence from Russia or, as is the case with Volga Tatars, have their own autonomous republic.

Although Soviet authorities officially allowed Crimean Tatars to return to the Crimea — on September 5, 1967, an order by Mikhail Georgadze gave Crimea Tatars the right to live “anywhere” in the USSR — Moscow refused to organize a return effort with logistical support, was lackadaisical in disputing earlier Stalinist propaganda, placed the legal residency status of Tatars in the hands of Crimean officials, and made discriminatory residency laws. In fact, using the Soviet internal passport system that determined all Soviet citizens’ legal residency status, local police, and KGB in Crimea denied individual Tatar’s residency registration. Through the registration system, Moscow banned former criminals from residing in big cities and resort areas such as Sevastopol, Feodosia, and Yalta. Despite all the obstacles, some Tatars did register throughout especially the 1970s and 1980s, while many thousands more squatted in rural and urban areas and fought prolonged battles for residential registration and reclaiming confiscated land. In response to the difficulties in returning, during the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, Crimean Tatars developed a human rights movement that established connections with other Soviet dissidents and the international human rights movement.

As the Soviet Union collapsed, what had been an intermittent flow of thousands of Tatars returning to the Crimea became a flood of tens of thousands from 1989 to 1991. However, the internal passport and registration laws remained a factor, and Tatars had a hard time establishing themselves in larger cities, although the establishment of a Tatar representative body known as the Mejlis has provided Tatars a voice in Kyiv and on the Crimean peninsula.

But the Russian presence and the attempt to eradicate the Tatar population has had crucial impact. The Black Sea Fleet, whose base in Crimea is guaranteed until 2042, remains the symbol of Russian naval power. The tourist industry and resort culture of the Crimea has remained vital to Russian culture. Many Russians have Crimean summer homes and Russian sailors often retire in the pleasant Black Sea climate.

When the subject of the “gift” of the Crimea to Ukraine comes up, this conversation must include a basic understanding of Crimean Tatar history and the history of the relative autonomy of Russians and Ukrainians in the Crimea from Moscow. Tatars have little reason to trust Moscow after centuries of being on the receiving end of the worst of Russian Imperial and Soviet policies. At the same time, local Crimean officials who are ethnic Russians and Ukrainians have maintained their post-1944 control over the peninsula partly with Moscow’s blessing, and partly with a form of control that gives local officials a large degree of autonomy. This is helpful in understanding why the pro-Russian rhetoric right now has been in favor of a new Autonomous Crimean Republic. The big question is how will any new republic compromise with Tatars and how much autonomy it will have from Kyiv or Moscow.

Andrew Straw is a historian of Soviet Crimea. He has taught courses on Russian and Soviet history at the University of Texas and Huston-Tillotson University. At the moment, he teaches high school world history and is an instructor for the University of Texas OnRamps history program. He continues research as an independent scholar and is preparing a book proposal that will focus on Stalin’s Crimea policy and Crimean Tatars in the immediate postwar period. He can be reached at astraw@utexas.edu or on Twitter at @astrawism1.

Banner Image: Crimean Tatar family, 1925. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Further Reading:

Alan Fisher, The Crimean Tatars (Stanford: Hoover Institution Press, 1978)

Edward J. Lazzerini, “Ismail Bey Gasprinskii: The Discourse of Modernism and the Russians,” in Edward Allworth, The Tatars of the Crimea: Return to the Homeland (1998)

Greta Lynn Uehling, Beyond Memory: The Crimean Tatars’ Deportation and Return, (2004)

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.

Just as the demonstrations were winding down, this group of young women, dressed in boldly colored dresses and tights, and masking their faces with equally bright balaclavas, or ski masks,

Just as the demonstrations were winding down, this group of young women, dressed in boldly colored dresses and tights, and masking their faces with equally bright balaclavas, or ski masks,

Caught in the middle of this complex maze of post-Soviet change is popular culture, which “finds itself torn between its own heritage and that of the West, between its revulsion with the past and its nostalgic desire to re-create the markers of it, between the lure of the lowbrow and the pressures to return to the elitist prerevolutionary past.” The quest to find, maintain,and alter cultural identity manifests itself in a variety of ways, which accounts for the large scope of this study.

Caught in the middle of this complex maze of post-Soviet change is popular culture, which “finds itself torn between its own heritage and that of the West, between its revulsion with the past and its nostalgic desire to re-create the markers of it, between the lure of the lowbrow and the pressures to return to the elitist prerevolutionary past.” The quest to find, maintain,and alter cultural identity manifests itself in a variety of ways, which accounts for the large scope of this study.