In the last decade, the history of Muslims in America has come into its own and A History of Islam in America provides one of the most comprehensive and even-handed treatments of the subject. Many previous studies breezily pit “Islam” against the “West.” Sidestepping the assumption that the two categories are essentially different, GhaneaBassiri studies the actual lived tradition of Muslims in America instead of second-guessing their compatibility.

Many previous studies breezily pit “Islam” against the “West.” Sidestepping the assumption that the two categories are essentially different, GhaneaBassiri studies the actual lived tradition of Muslims in America instead of second-guessing their compatibility.

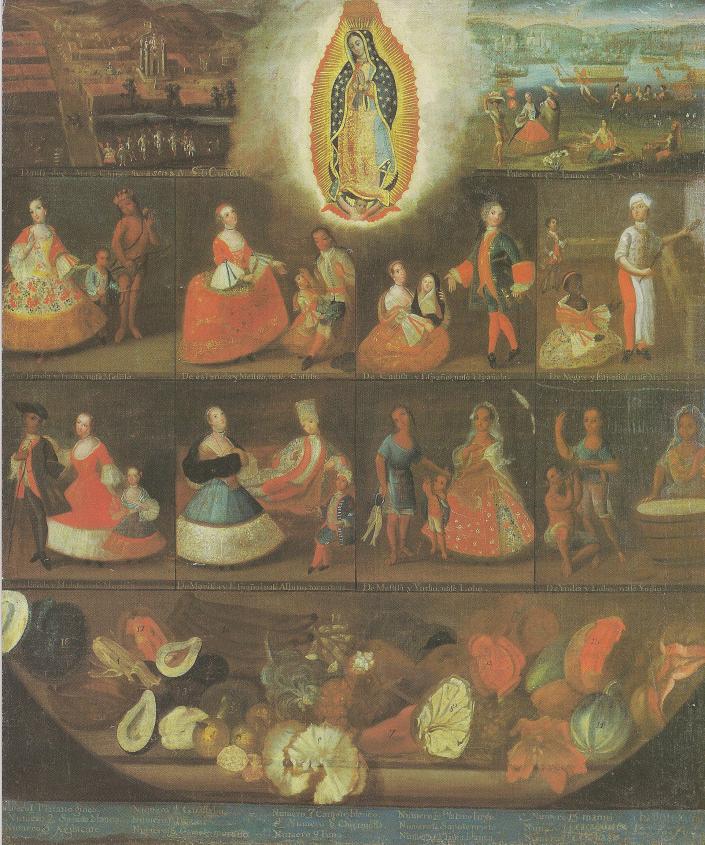

America has been home to Muslims for a long time. Compelling stories come to the fore. Some Muslims arrived in the New World before slavery, like the adventurous sixteenth-century Moroccan cowboy and healer, Estevanico. Enslaved African Muslims sometimes resorted to private worship and remained active in their local communities. The story of Selim, an Algerian captive who petitioned for his freedom, is fascinating. Understanding his constraints, Selim converted to Christianity and, as a result, received economic and political benefits. He finally earned enough money to return to Algeria as a free man. Once there, he reverted to Islam.

Much past research about Islam in the West has focused on perceptions. For instance, Timothy Marr’s The Cultural Roots of American Islamicism and Susan Nance’s How the Arabian Nights Inspired the American Dream: 1790-1935 study only non-Muslim Americans’ representation of Islam. But images of Muslims in literature and political propaganda are not the only sources at our disposal. The historical records of Muslim individuals and institutions show that in the past four hundred years, Islam and America have interacted and the relationship between the two has defined each. Islamic America, like the rest of American society, is not one uniform set of communities, practices or symbols, but it has nonetheless existed in different forms continuously on this side of the Atlantic.

American political, legal, and civic institutions have provided many ethnic and religious groups, not only Muslims, with opportunities for participation mixed with doses of exclusion. GhaneaBassiri tells us of Muslims who collaborated and challenged these norms through organizations of their own. In the period between the two world wars, Islamic community building took root in mosques and benevolent societies like the Moorish Science Temple and the Nation of Islam. Islam allowed black Muslims new tools for rethinking race, religion, and progress in the aftermath of World War II when optimism about human accomplishment waned. Civil Rights legislation offered opportunities for immigrant Muslims by declaring loudly that discrimination based on race would not be tolerated. A positive, if accidental, symptom of immigration reform was the realization that the Muslim community also struggled for self-reliance.

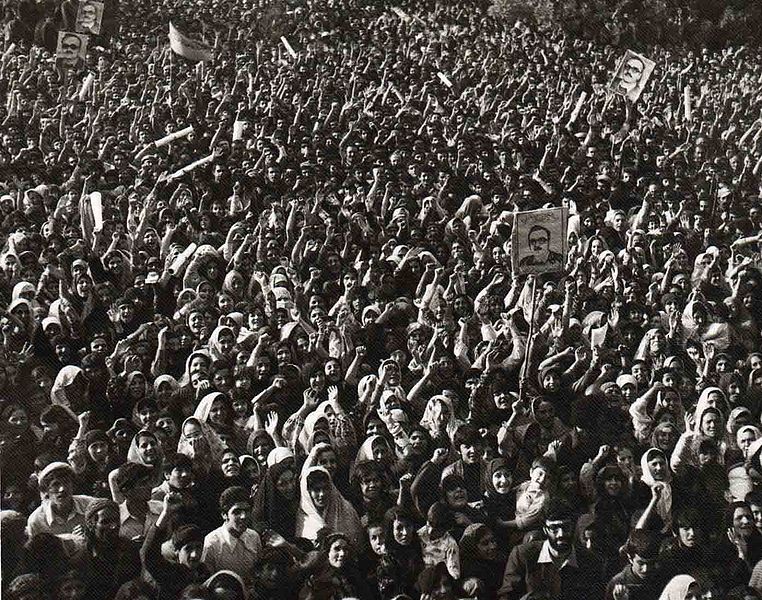

In the wake of the 1979 Iranian Revolution and the popular American use of the term “Islamic terrorism” in place of “Arab terrorism,” Muslims in the United States continued to participate in activism. Optimistic that their adopted land gave them substantial socio-economic and political advantages, Muslims also realized that prejudice, like anything else, fades through interaction. Today, the juggernaut terms “Islamic terrorism and fundamentalism” are the focus of U.S. foreign policy rather than Cold War enemies. But at the same time, GhaneaBassiri believes that American Muslim objectives continue to show increased diversity. With a multiplicity of institutions, Muslim groups and organizations have ties to non-Muslim institutions and individuals. These relationships, bonds and experiences testify to a larger and more varied experience than merely cultural conflict. This book drives home the point that America’s historical encounter with Islam has not been a clash. But, as the author explains, we can only get our arms around it when we look at how Muslims actually lived on American soil.

Photo credits:

Marion S. Trikosko, “President Jimmy Carter greets Mohammad Ali at a White House dinner celebrating the signing of the Panama Canal Treaty, Washington, D.C., 7 September, 1977”

Library of Congress

Kamal al-Din, People Marching before the Iranian Revolution

Author’s own via Wikimedia Commons

You may also like:

Lior Sternfeld’s review of Erez Manela’s book about Woodrow Wilson and the origins of anti-colonial movements in Africa and Asia.

UT Professor Yoav di-Capua’s blog post about political and social conditions in Egypt eight months after Mubarak’s ouster in February 2011.

Kristin Tassin’s review of Zachary Lockman’s 2004 book Contending Visions of the Middle East: The History and Politics of Orientalism.

Covering a wide sweep of history, Westad argues that the United States and the Soviet Union were driven to intervene in the Third World by the ideologies inherent in their politics.

Covering a wide sweep of history, Westad argues that the United States and the Soviet Union were driven to intervene in the Third World by the ideologies inherent in their politics.

by

by