BioShock Infinite

Irrational Games

I have spent most of the last year applying for jobs, which means that I have spent most of the last year analyzing, constructing, rewriting, and generally just staring at my résumé. Writing a résumé is similar to creating a historical narrative – there is a protagonist (you), a cast of characters (employers and recommenders), a beginning, an end, a series of events in the middle, and a whole set of details that can be added or removed to suit particular audiences. Given the economy right now, there is pressure to make this narrative as broadly appealing as possible. Some career advisors have even encouraged me to engage in “creative truth-telling” to help me land a position. This practice, they tell me, isn’t lying, per se, but rather a gentle embellishment of the facts.

As an historian, however, this practice gives me the heebie jeebies. It reminds me too much of the push by some to make a selective reading of American history the standard for teaching the subject. American History, in many ways, represents the nation’s résumé. It is a catalog of achievements and events – some good, some regrettable – that are used to encourage citizens and outsiders to buy into the nation. As with my own personal narrative, the stakes for this résumé are high. There is the same pressure to embellish this history – both through addition and omission. But we must ask if it is really beneficial to avoid all the nasty bits when studying the past? When we consider our own personal failures, we often say that we learn from our mistakes. How can we learn from the nation’s mistakes if we remove them from our history?

BioShock Infinite is a game that uses a counterfactual history of the United States to force players to consider some of these mistakes. Set in 1912, the game takes place in Columbia, a floating city hovering over the United States. You play as Booker DeWitt, a veteran of the 7th Cavalry Regiment and a former member of the Pinkerton Detective Agency, who is sent to Columbia to retrieve a girl named Elizabeth in order to absolve his debt. Booker is racked by guilt for his participation in the Wounded Knee Massacre and for his role in putting down worker strikes as a Pinkerton agent. His personal remorse has driven him to drinking and gambling. Booker embodies several Progressive Era sensibilities, including the awareness of past wrongs, and the desire for redemption and reform.

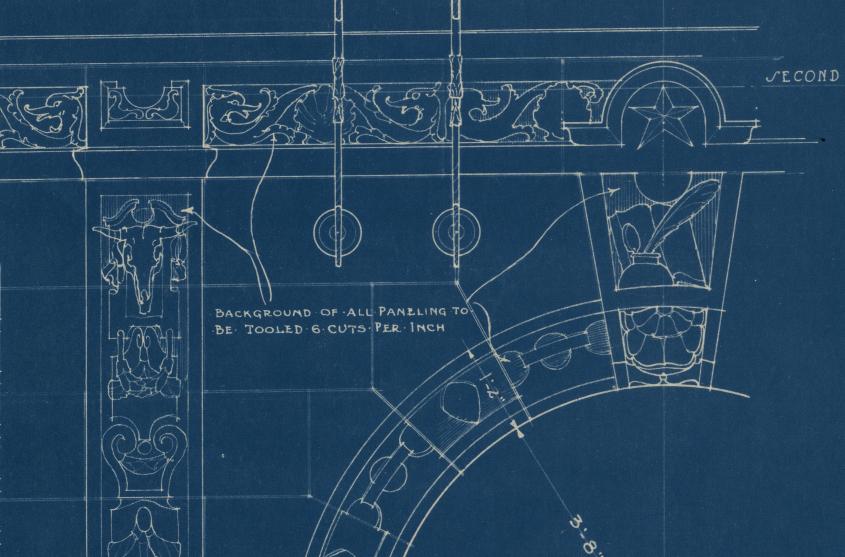

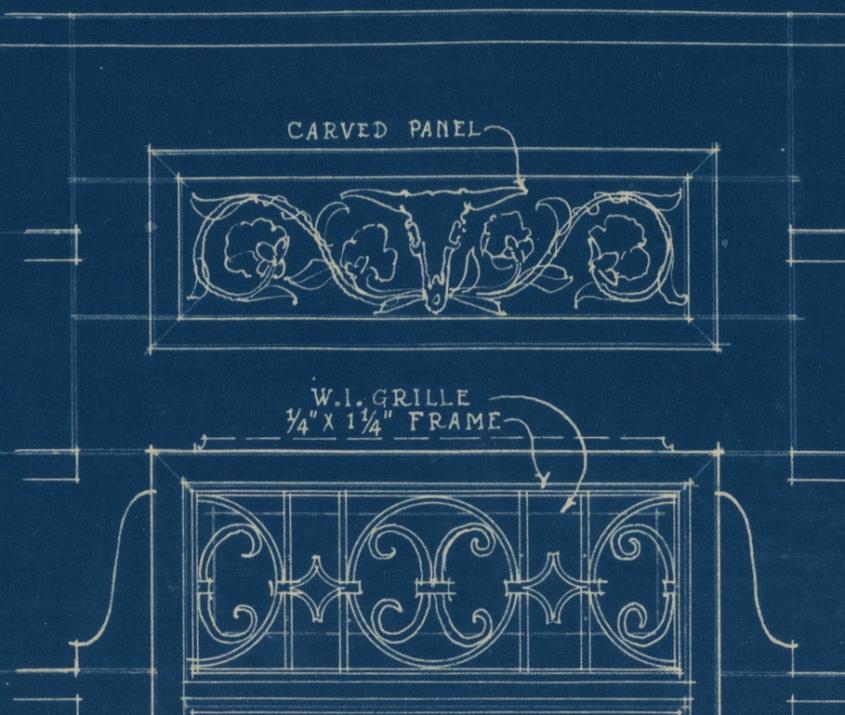

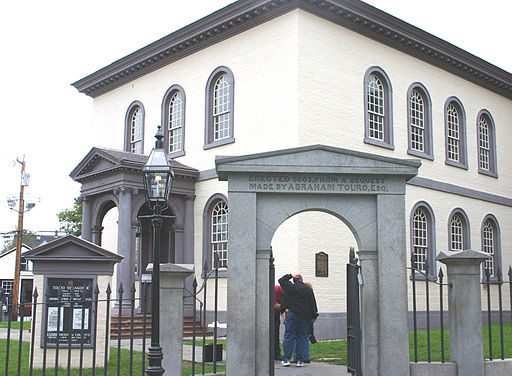

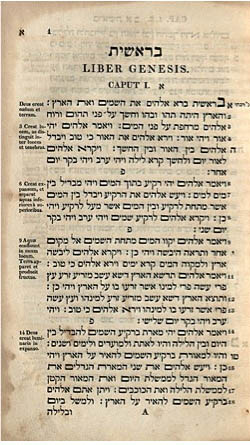

In Columbia, however, Booker faces an unrepentant Gilded Age society led by firebrand preacher Zachary Comstock – a man who shares much of Booker’s personal history, but none of his remorse. Styling himself as a modern day Noah, Comstock sees Columbia as “another ark, for another time,” a place where he can preserve his vision of America while planning the destruction of “the Sodom below.” Comstock’s America is built upon a perverse worship of the Founding Fathers and rejection of the political and social developments in American society since the Civil War. Columbian society is committed to racial purity, religious zealotry, and unfettered capitalism, and promotes these philosophies through a set of distorted Sears Roebuck advertisements plastered around the city. Museums in the city present John Wilkes Booth as a hero and the Wounded Knee Massacre as a national triumph. The personal histories of DeWitt and Comstock reminds players not only of particular historical events, but also how the memories of those events can be perverted to attain political goals.

This sort of stylistic use of history is familiar territory for Irrational Games and its creative director, Ken Levine. The original BioShock, published in 2007, used Ayn Rand’s objectivist philosophy as the basis for a story set in the underwater city of Rapture. Levine’s BioShock games share many similarities in terms of plot and theme. Both games feature an antagonist bent on creating a utopian society based on warped notions of exceptionalism and capitalism. These antagonists are opposed in both instances by a group made up of dissatisfied, working class civilians, led by Frank Fontaine in BioShock and Daisy Fitzroy in Infinite. Thematically, the BioShock series grapples with the age old question of free will versus destiny, and stresses the potential role of the state in determining the answer.

notions of exceptionalism and capitalism. These antagonists are opposed in both instances by a group made up of dissatisfied, working class civilians, led by Frank Fontaine in BioShock and Daisy Fitzroy in Infinite. Thematically, the BioShock series grapples with the age old question of free will versus destiny, and stresses the potential role of the state in determining the answer.

Both BioShock games offer easy parallels with the present division between neoliberal capitalists and the Occupy Movement, yet these parallels become murky as both games progress. While the capitalist appears as the initial antagonist in both games, the player comes to learn that the opposition is capable of just as much destruction and violence. Levine’s message, then, is not a simple liberal critique of current politics, but rather a general warning about extremism in politics, whether that extremism comes from the left or the right. Writing as an historian of the 20th century, this is a warning that cannot be repeated too many times.

In addition to the plot and themes, BioShock Infinite encourages historicism through its music and gameplay. For reasons that become clear through the story, Infinite contains a jukebox musical score that features ragtime versions of popular twentieth-century hits, including songs by the Beach Boys, Creedence Clearwater Revival, Cyndi Lauper, Lead Belly, Soft Cell, and Tears for Fears. Additionally, Infinite’s gameplay often encourages the player to take on the role of historian. Major elements of the game’s narrative are left unexplained in cut scenes, but can be found by the player in voice recordings and kinetoscopes scattered throughout the city. These recordings and logs are not always easy to find, meaning that each player can come away with a different sense of the storyline depending on which, or how many, recordings they discovered. One of the game’s major side quests, then, is an oral history scavenger hunt.

This sort of detailed work would be lost on most players without exciting gameplay to draw them in. Infinite, however, builds upon traditional first-person action in interesting ways. In particular, it takes advantage of the game’s setting in the clouds, allowing players to move around the environment using skylines and zeppelins. This freedom of movement gives the combat sequences a frenetic feel and prevents them from becoming predictable. Unfortunately, this novelty is diminished by the rote nature of the game’s violence. The current debate on graphic content in video games is all too applicable here. Infinite’s storyline, including the player’s interactions with their companion Elizabeth, are best experienced by the reader themselves. The plot is a bit more precocious than profound, but it is well paced, matching the action of the game.

This sort of detailed work would be lost on most players without exciting gameplay to draw them in. Infinite, however, builds upon traditional first-person action in interesting ways. In particular, it takes advantage of the game’s setting in the clouds, allowing players to move around the environment using skylines and zeppelins. This freedom of movement gives the combat sequences a frenetic feel and prevents them from becoming predictable. Unfortunately, this novelty is diminished by the rote nature of the game’s violence. The current debate on graphic content in video games is all too applicable here. Infinite’s storyline, including the player’s interactions with their companion Elizabeth, are best experienced by the reader themselves. The plot is a bit more precocious than profound, but it is well paced, matching the action of the game.

The BioShock series has become something of a bellwether for the video game industry and the release of Infinite has led to several “state of the medium” pieces online (listed below). What, then, does BioShock Infinite indicate about the future course of video games? On the one hand, we see a familiar reliance on violence and the first-person perspective, but on the other hand, we see a game that engages with complex, historically laced themes. Certainly, Infinite presents these themes in an exaggerated manner, but the fact that the game deals with them at all is encouraging. This further maturation of video games can only be seen as a good thing, for historians and players alike.

Photo Credits:

Promotional Photos of Bioshock Infinite (Images courtesy of Irrational Games and 2K Games)

Images used under Fair Use Guidelines

If you’d like to read more about Bioshock Infinite:

Leigh Alexander writes that Infinite represents “a crucial moment in