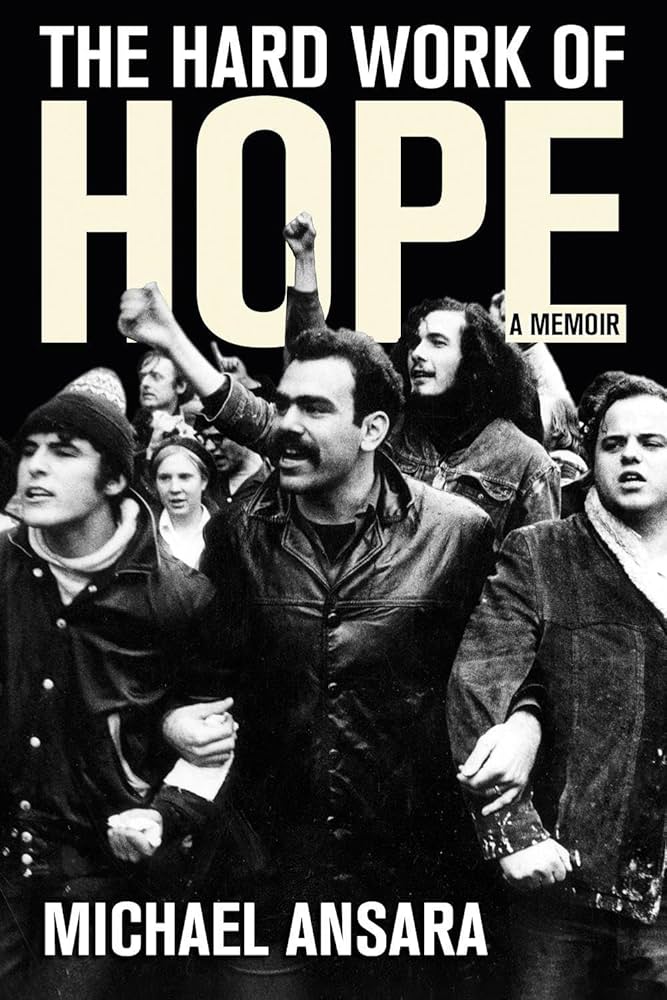

In his recent memoir, The Hard Work of Hope, activist Michael Ansara reflects on decades of organizing experience in the U.S. civil rights, student, and anti-war movements. Raised in Boston, Ansara was one of many Northern students who came of age following World War II and, drawing inspiration from the Southern civil rights struggle, organized opposition to the Vietnam War on college campuses. Ansara began his career as an activist in high school, working with a local civil rights organization, the Boston Action Group (BAG), to develop campaigns around issues like employment discrimination and tenants’ rights. Later, as a student at Harvard University, Ansara joined Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) and became a leading voice in the anti-war movement of the late 1960s and early 1970s. Following the war, he helped to build Massachusetts Fair Share, an organization that addressed local and neighborhood-level concerns ranging from utility rate hikes to zoning laws.

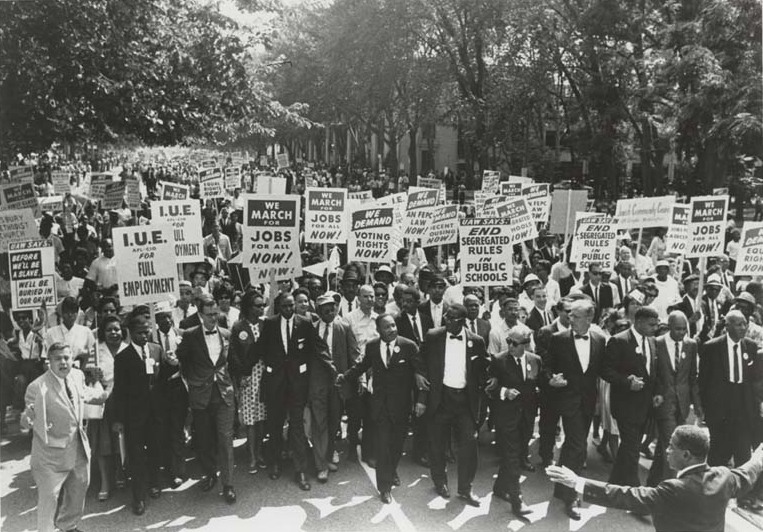

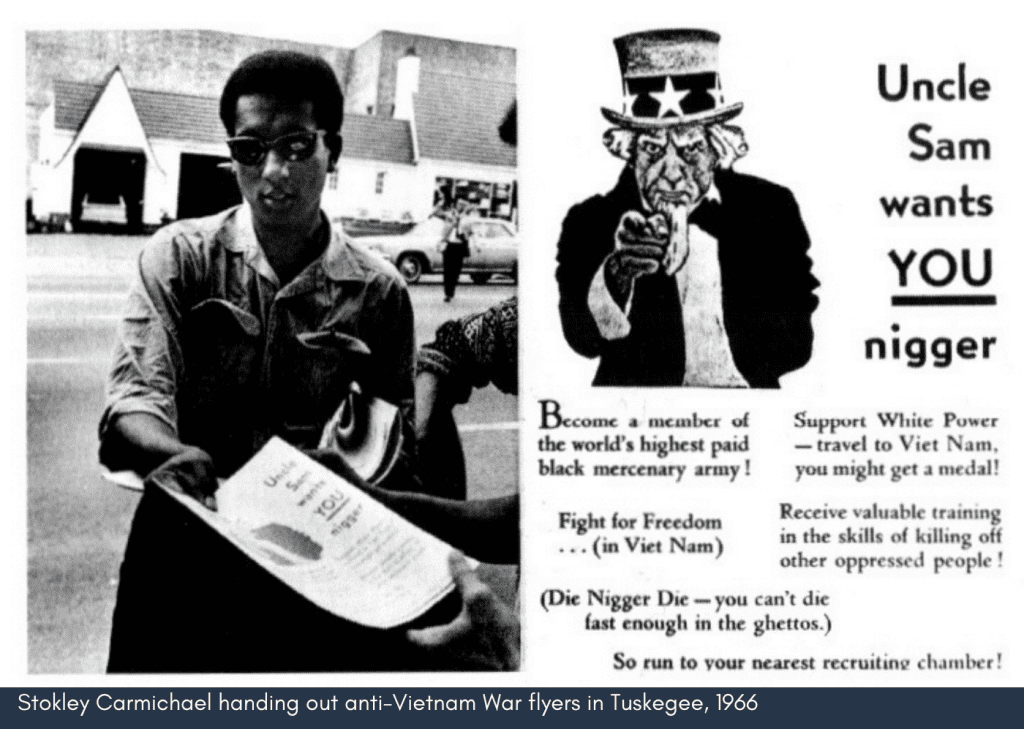

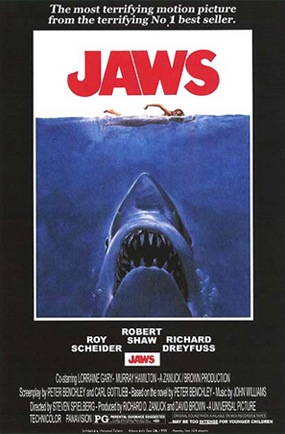

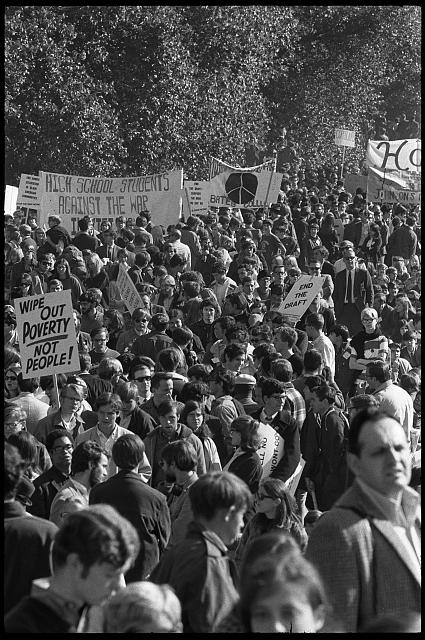

Most of the book is devoted to Ansara’s anti-war activism while at Harvard and shortly after graduating. As U.S. involvement in Vietnam escalated over the course of the 1960s, many American students began to protest what they viewed as an unjust and immoral war. They organized massive rallies and demonstrations, circulated literature, and engaged in civil disobedience. Ansara was involved in planning and executing major campaigns at Harvard, including the occupation of University Hall and the subsequent student strike in 1969. As its title suggests, however, the book does not only document the flash points of the student movement —the massive rallies and confrontations with law enforcement. Rather, Ansara places emphasis on the day-to-day work of engaging with ordinary people and compelling them to act. As he notes, “It is easy to write about the demonstrations, the marches, the confrontations. They were dramatic and essential. However, they were only possible because of long hours of outreach, discussion, connecting. It was the mundane work of reaching out to students that occupied me, and the other SDS organizers, and that made it possible for people to join the march, get on the bus, join the movement” (p. 48). Far from being inevitable, the successes of the anti-war movement were the result of years of planning and organizing by activists who often encountered fierce opposition from law enforcement, their peers, and the public.

[Large crowd at a National Mobilization to End the War in Vietnam direct action demonstration, Washington, D.C.]

Source: Library of Congress

Throughout the book, Ansara also reflects on what he perceives as the failures of the anti-war movement. For instance, he acknowledges that many activists failed to offer concrete support to Vietnamese refugees and veterans after the war ended. He also addresses the creation of groups like the Weathermen, a radical offshoot of SDS that utilized political violence. Ansara was deeply critical of the group’s strategies, but he also recognized the role that state repression played in its development.

Ansara’s discussion of movement strategy and structure is particularly useful, and several ideas may resonate with contemporary readers. First, Ansara argues that the anti-war movement would have been more effective had it embraced electoral politics alongside direct action protest. Second, he distinguishes strategies from demands. Early on, anti-war activists focused on capturing public attention with bold and confrontational protests. Once the public was receptive to their message, however, many groups failed to deliver clear and actionable demands. Ansara suggests that a straightforward program of action is essential for organizing. Lastly, Ansara challenges the idea that a movement can be truly “leaderless.” Organizations like SDS rejected formal leadership structures as hierarchical and undemocratic. Yet, as Ansara notes, this often gave way to informal—and, thus, unaccountable—leaders making all of the decisions. He writes, “Every social movement and every organization has leaders, formal or informal. The question is not whether we have leaders, but whether we have good leaders, leaders who empower others, who build successors, who are accountable. In SDS, the confusion over leadership inhibited our effectiveness, allowing young, arrogant men like me to lead without being held accountable” (p. 258).

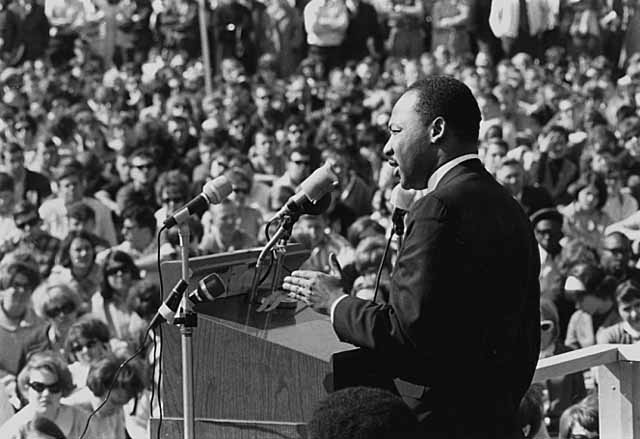

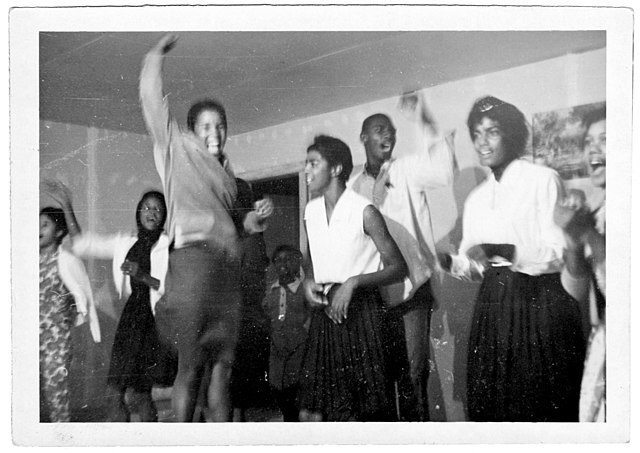

Freedom Summer. Source: Wikimedia Commons

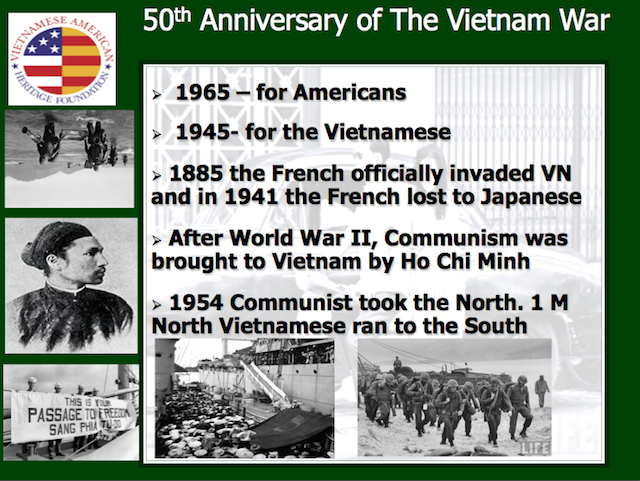

While the book does address the larger political context in which activists like Ansara operated, some of the events mentioned in passing deserve further explanation, particularly for younger audiences and for those without a background in history. For example, Ansara references the bombing of 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, and the murder of three civil rights workers—James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner—during Mississippi Freedom Summer on several occasions without fully explaining what happened or how it shaped the larger social landscape. More thoughtful analysis of these events would provide important context for readers by highlighting the violent opposition that activists faced, especially in the Deep South. Moreover, as Ansara acknowledges, his memoir is a deeply personal reflection on his experience as an activist, and it should not be taken as a representation of the anti-war movement as a whole. Student organizing on college campuses was a crucial part of this broader movement, but there were many other manifestations of anti-war activism that cut across lines of gender, race, and socioeconomic status. Finally, while Ansara reflects critically on student organizing during the Vietnam War, he is less forthcoming about his later life, including the dissolution of Massachusetts Fair Share due to financial mismanagement under his leadership and his subsequent failed business ventures. Although some readers may appreciate Ansara’s focus on his anti-war activism, others may be left desiring a more complex portrait of his life that grapples with some of these contradictions.

Ultimately, The Hard Work of Hope represents a valuable resource for a number of audiences. For scholars researching anti-war and student activism during the 1960s and 1970s, Ansara’s narrative offers a firsthand account of key campaigns, such as student protests against Dow Chemical and the Harvard Strike. Educators might also incorporate excerpts of this book into undergraduate or high-school classrooms as an example of a primary source for analysis. Finally, and perhaps most importantly, Ansara’s memoir offers valuable insight for those currently organizing for a more just and equal society on college campuses and beyond.

Sarah Porter is a Ph.D. student in the Department of History at the University of Texas at Austin. She studies twentieth-century social movements, policing, and mass incarceration in the United States.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.