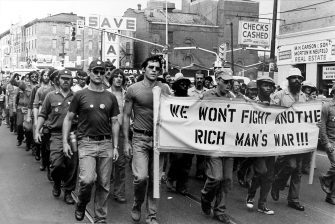

This week, the discussion delves into the complex and deeply rooted suffering in the Middle East, focusing on the history of conflict, memory, trauma, and grief between Israelis and Palestinians. Jeremi and Zachary Suri are joined by acclaimed author Lawrence Wright, who has spent decades studying and documenting the region. Wright discusses his latest novel, ‘The Human Scale,’ which examines the motivations and personal stories behind the ongoing violence and suffering.

Zachary sets the scene with his poem, “In Jerusalem”.

Lawrence Wright is a staff writer for The New Yorker, a playwright, a screenwriter, and the author of ten books of nonfiction, including The Looming Tower, Going Clear, and God Save Texas, and three previous novels, Mr. Texas, The End of October, and God’s Favorite. His books have received many honors, including a Pulitzer Prize for The Looming Tower. His most recent book is a novel, The Human Scale.