By Michael Gillette

At the annual meeting of the Texas State Historical Association in March 2011, the luncheon for Women in Texas History was dedicated to Liz Carpenter. Among the remarks and remembrances, Michael L. Gillette, the Executive Director of Humanities Texas, offered a wonderful tribute based on materials and photographs from the LBJ Library & Museum at UT Austin. We were so impressed by the talk that we asked Mr. Gillette if we might reprint his presentation and he graciously agreed.

I met Liz in the days after President Johnson’s death in 1973, when I was detailed to work with her on a eulogy book. She was then at the zenith of her career: a savvy force in politics, a celebrated author, and a national leader of the women’s movement. But she also had the aspect of a small town Texas girl: approachable, fun-loving, quick to befriend, down-to-earth, and never taking herself too seriously.

She displayed this duality one evening at the Old Coupland Inn during one of her visits to Austin in the mid-1970s. Five couples in caravan accompanied her, but Liz herself had no escort that evening. I remember that almost as soon as we arrived, a lively Texas swing band enticed all of us onto the floor of the Old Dance Hall. And as LeAnn and I were dancing, I looked up and saw that Liz was dancing with some local cowboy. She was easy to spot, by the way, because, in this maze of denim, she was wearing a bright, rainbow-colored psychedelic tent dress.

Later, she later satisfied my curiosity by repeating her conversation with the cowboy as she herded him onto the dance floor.

“Where are you from?” she asked him.

“Elgin,” he replied. “Where are you from?”

“Salado,” she declared with the confident pride of one who had spent her entire life just up the road. She neglected to mention she hadn’t lived there since the 1920s and that she had been a Washington, DC resident for the past thirty years.

But Salado was, in a sense, her home: her birthplace, her ancestral legacy, and the coordinates that defined her sense of place. “All my life I have drawn strength” from Salado,” she wrote. There she found a singular peace, “a reverence before this altar of ancestors.”

Her great, great grandfather, Sterling Clack Robertson migrated from Tennessee to Texas to become the Empresario of Robertson’s Colony. He was a signer of the Texas Declaration of Independence, which Liz’s great, great uncle, George Childress, drafted. Robertson’s son, Elijah Sterling Robertson, founded Salado and built the 24-room plantation house where Liz was born.

Meanwhile, Liz’s paternal forbears migrated from Alabama to form the Settlement in Jackson County. George Sutherland fought at the Battle of San Jacinto after his son William died at the Alamo.

Liz’s family tree sprouted strong, adventurous women equal to the men. A great aunt, Louella Robertson Fulmore, eloquently advocated educational equality for women.  Another great aunt, the prominent suffragist, Birdie Johnson, became the first Democratic national committeewoman from Texas. As she exhorted women to organize to make their influence felt at the polls, she declared that it was “our first step” in the exercise of “direct political power.” No wonder Liz believed that she had inherited her feminist genes.

Another great aunt, the prominent suffragist, Birdie Johnson, became the first Democratic national committeewoman from Texas. As she exhorted women to organize to make their influence felt at the polls, she declared that it was “our first step” in the exercise of “direct political power.” No wonder Liz believed that she had inherited her feminist genes.

She was not blind to the shortcomings of her ancestors, whose reputations bore the stain of enslavement and the tragic folly of secession. Nor did her rich Texas legacy confer a sense of privilege or birthright. Instead, it affirmed her belief that ordinary people can overcome adversity to accomplish extraordinary things.  It also instilled a love of Texas history and a respect for its historians, which is why this award meant so much to her. Finally, it inspired one of greatest political zingers of all time. When John Connally threw his support to the Republican incumbent President in 1972 and formed a group called “Democrats for Nixon,” Liz declared that if Connally had been at the Alamo, he would have organized “Texans for Santa Anna.”

It also instilled a love of Texas history and a respect for its historians, which is why this award meant so much to her. Finally, it inspired one of greatest political zingers of all time. When John Connally threw his support to the Republican incumbent President in 1972 and formed a group called “Democrats for Nixon,” Liz declared that if Connally had been at the Alamo, he would have organized “Texans for Santa Anna.”

Liz’s family moved to Austin when she was seven years old, so that she and her older siblings could ultimately attend the University of Texas. This was a transition that prepared her for the wider world. By the time she graduated from UT with a degree in journalism, she sensed that her prose and her spirit would enable her to make her mark. “Give me wide open spaces, a Model T, and a typewriter,” she wrote to her mother, “and I’ll see you in the hall of fame.”

Although Washington, DC in 1942 was hardly “the wide open spaces,” it was the perfect place for a young woman to test her potential. With men in uniform, the city opened its doors to women as never before.  When Liz made a courtesy call on her congressman, she discovered that his wife was running the office while he was overseas. It was that visit that introduced Liz Carpenter to Lady Bird Johnson.

When Liz made a courtesy call on her congressman, she discovered that his wife was running the office while he was overseas. It was that visit that introduced Liz Carpenter to Lady Bird Johnson.

Liz secured a job with Esther Tufty, as a secretary and cub reporter. In this latter capacity, she was able to cover the press conferences of Eleanor Roosevelt, who was redefining the role of First Lady, and Frances Perkins, Secretary of Labor and the first woman to hold a cabinet post. After Liz married Les, her college sweetheart, the couple formed their own news bureau, covering Capitol Hill for 26 Southwestern newspapers.

But the Carpenters’ three decades in Washington were hardly an exile from the Lone Star State. Texas was in the midst of a seismic transformation into a modern urban state. Its leaders and entrepreneurs were flocking to Washington, seeking federal help to make their dreams a reality. Liz had a ringside seat from which to observe this remarkable saga as it unfolded. While she gained an insider’s knowledge of how things work in government, politics and human nature, she also acquired a wealth of friends and associates. Within a decade she was elected president of the Women’s National Press Club.

Aiding Liz’s emergence was an almost mystical fraternity in Washington, the Texas establishment. Among Texans in the capital, there was a unique bond that no other state’s natives enjoyed. The Texas State Society was, by far, the largest and most active of the city’s state organizations. There was even a Texas investment group: the Longhorn Longshots Club, to which Liz and Les belonged. As always, Liz had just the right phrase for this establishment.

She called it “the Texas family.” It was a group that worked together, dined together, and entertained together. Their children grew up together, forming second generation friendships.

The center of the Texas family was the large, powerful, and close-knit Congressional delegation. There was Speaker Sam Rayburn, Wright Patman, George Mahon, Tiger Teague, Bob Pogue, Clark Thompson, Homer Thornberry, Joe Kilgore, and, of course, Lyndon Johnson.

Clark and Libbie Moody Thompson entertained Texans so often that their elegant home became known as the Texas Embassy. And on countless Sundays, the four Carpenters–Liz, Les, Scott, and Christy—would spend the afternoons, at the Johnson home with Speaker Rayburn, other members of Texas congressional delegation, and the Texas press and their families. The topic of discussion was always politics. What an extraordinary postgraduate education these afternoons must have been!

Clark and Libbie Moody Thompson entertained Texans so often that their elegant home became known as the Texas Embassy. And on countless Sundays, the four Carpenters–Liz, Les, Scott, and Christy—would spend the afternoons, at the Johnson home with Speaker Rayburn, other members of Texas congressional delegation, and the Texas press and their families. The topic of discussion was always politics. What an extraordinary postgraduate education these afternoons must have been!

Then, when Liz was in Chicago covering the 1960 Republican convention, she received a phone call that changed her destiny. Lady Bird Johnson asked her to share the great adventure of their lives and travel with her in the presidential campaign.

That telephone call put Liz on a fast track to fame: a vice president’s staff; two presidential campaigns; and countless domestic and international trips that enabled her to see America and the world as few of us ever do. She wrote the new President’s words that would comfort a nation in shock after President Kennedy’s assassination. As Lady Bird Johnson’s Press Secretary and Staff Director, Liz was in the forefront of such major initiatives as Head Start, beautification, and the creation of so many national parks.

With her destiny bound to that of Lady Bird Johnson, the fame that had been a fantasy of Liz’s youth, found both women. Yet, their differences were as striking as their similarities. Both were keenly intelligent, well-informed, and profoundly curious about the world around them. Both were happiest when they were working, striving to make the world a better place. But Mrs. Johnson was judicious, disciplined, cautious and firm, but gentle. Liz, on the other hand, was bawdy, daring, feisty, creative, loud and hilarious.

I recall a single moment that highlighted their differences. Each January, Mrs. Johnson hosted a group of friends at a rented villa high above Acapulco Bay. I was interviewing her in her room one morning when a very minor earthquake caused everything around us to shake. Mrs. Johnson paused from her narrative; her eyes widened briefly and then closed, as her lips formed a placid smile. She was the epitome of serenity in the face of uncertainty. Liz’s reaction, on the other hand, measured a 7.2 on the Richter scale. Tearing out of her room, she raced up to the Secret Service agent on duty and shouted: “What is this? An earthquake?”

“Yes, Ma’am,” he responded.

“Well, what are you going to do about it?”

Despite, or perhaps because of, their differences, these two remarkable Texas women shared a deep and enduring friendship of more than sixty years. For half of that span, both were widows who depended on the companionship and shared memories that only old friends can provide. One merely had to see them together to realize how much they cherished each other.

After leaving the White House, Liz did everything but retire. She wrote five books, crisscrossed the country on the speaker’s circuit, joined the public relations firm of Hill and Knowlton, served two other presidents, helped raise a second family, and became a national leader of the women’s movement.

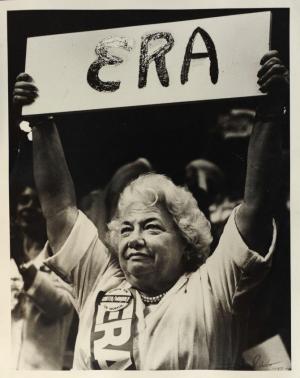

“A day that changed my life,” was Liz’s description of the historic meeting at the Statler Hotel in 1971 when she and other leaders organized the National Women’s Political Caucus. Betty Freidan enlisted Liz because the movement needed her political expertise and her knowledge of the press. But remember that it was the Texas family that had nurtured and equipped her for this new role. Her ancestral family, too, had led her to this new path: “In my ancestors,” she wrote, “I keep finding me. I keep finding that their causes are my causes.”

This last great odyssey brought new friendships, new travels and challenges—and air travel for Liz was always a challenge. She used to say that “Any landing you can walk away from is a good one.” She became a role model, an advisor, and an inspiration to young women seeking to become active in civic life. By advancing the candidacies of so many Texas women, she helped change the face of power in our state.

Two years after Les’s death in 1974, Liz decided to move back to Texas. She bought a picturesque Austin home that became a nerve center for the social and political causes she espoused. An invitation from Liz was always a summons to adventure. You never knew what to expect until you were there. One could end up in her Jacuzzi with Gloria Steinem and Erma Bombeck or singing hymns with Ann Richards. Her guest house provided a haven for anyone needing shelter for a day or a year.

When Liz’s health began to decline, and she sensed her mortality, she planned her own send-off. She had already staged a dress-rehearsal at the Paramount Theater as a fund-raiser a number of years earlier. It was a hilarious roast with Lily Tomlin and Ann Richards, but all agreed that Liz, attired as an angel, stole the show.

When it was time for the real thing, almost a thousand friends and family told stories and laughed and cried, as she had ordained. Afterward, a smaller group made the final journey to that place that had always given Liz a special peace: Salado. As she had prescribed, her friends and family dutifully scattered her ashes and wildflower seeds on College Hill. Even on this sad occasion, they must have smiled when they remembered Liz’s final instructions: “If it’s a windy day, be sure to keep your mouth closed.”

Summing up her remarkable story, she once wrote that: “Life has always led me where things were happening; where people were exhilarating, where actions and laughter came quickly.” This extraordinary Texan, so worthy of the rich legacy she had inherited, schooled within a circle of greatness, nurtured by a wealth of friendships, and inspired by a spirit of adventure, wrote each chapter of her life as if it were the last. And she made every word count.

Photographs compiled by Lindsey Wall.

The views and opinions expressed in this article or video are those of the individual author(s) or presenter(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policy or views of the editors at Not Even Past, the UT Department of History, the University of Texas at Austin, or the UT System Board of Regents. Not Even Past is an online public history magazine rather than a peer-reviewed academic journal. While we make efforts to ensure that factual information in articles was obtained from reliable sources, Not Even Past is not responsible for any errors or omissions.