In 1930, historian William Warren Sweet wrote that the “conquest of the continent” was America’s greatest accomplishment and its churches’ “greatest achievement” involved “the extension of their work westward.” Drawing on Frederick Jackson Turner’s thesis about the importance (and closing) of the American frontier, Sweet’s classic and oft-read textbook identified westward movement as fundamentally important to American religion. Historians of American religions have rightfully turned away from Sweet’s conclusions. Indeed, since the 1960s the study of American religions has been transformed from a sleepy corner of the historical profession to what commentators have identified as an increasingly popular subfield. The scholarship now includes excellent monographs on long-neglected groups, oft-overlooked sources, and is shaped by theoretical insights from critical work on religion, race, gender, ethnicity, and labor. During the field’s much-needed transformation, the frontier faded into the background, at least for a time.

Historians of American religions have rightfully turned away from Sweet’s conclusions. Indeed, since the 1960s the study of American religions has been transformed from a sleepy corner of the historical profession to what commentators have identified as an increasingly popular subfield. The scholarship now includes excellent monographs on long-neglected groups, oft-overlooked sources, and is shaped by theoretical insights from critical work on religion, race, gender, ethnicity, and labor. During the field’s much-needed transformation, the frontier faded into the background, at least for a time.

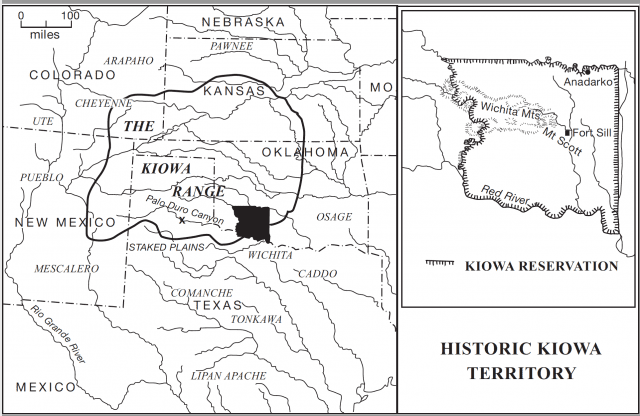

A new generation of scholars has returned to the frontier, bringing with them all the critical tools now available in the subfield. Rather than asking how religion fueled American expansion, they have investigated how the experience of expansion reshaped American religions, those practiced by both settlers and Native people. It’s within this new mode of writing that I set out to study the religious transformations prompted by the invasion and defense of lands inhabited by Kiowa Indians and later designated Indian Territory (and eventually Oklahoma) by Americans.

Americans got their first long-term experiences on Kiowa lands and engagements with Kiowa ritual activity when Quakers were assigned to administer the Kiowa, Comanche, and Apache Reservation in 1869. Ready to engage their fellow humans trapped in “heathen darkness,” Quakers distributed food rations, organized schools, and held meetings for worship among the reservation’s more than 5000 Native occupants. Quaker workers frequently mentioned Kiowa “superstition” as the greatest obstacle to their acculturation of Euro-American habits and assimilation into American life.

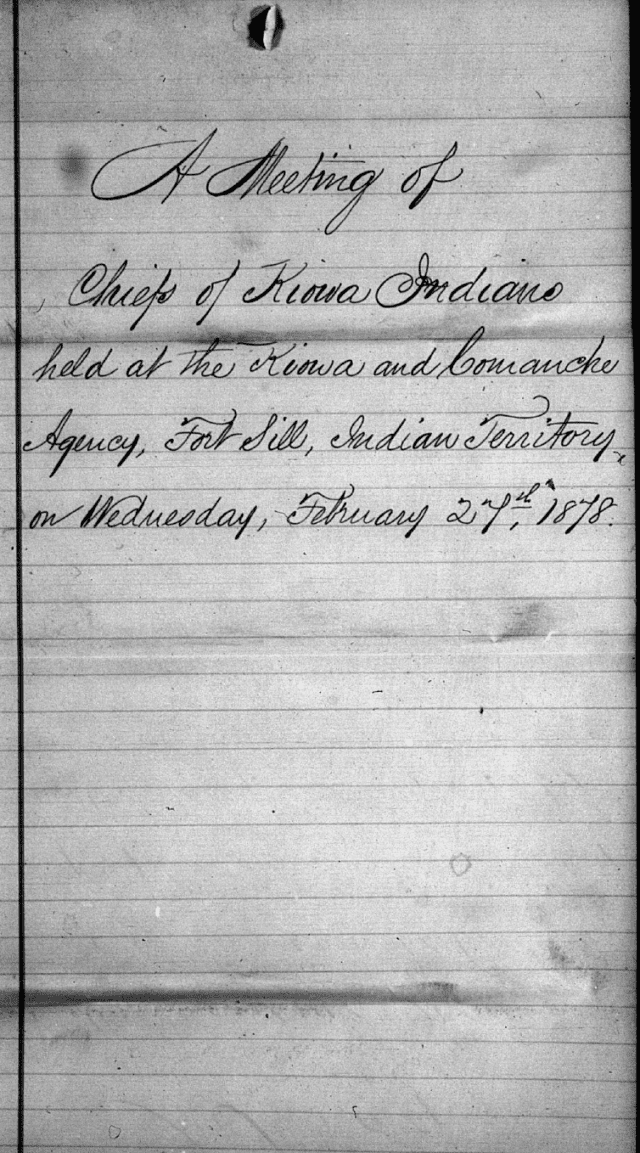

Several years later, however, a Quaker administrator saw something he recognized as real religion. Kiowa elders and young men requested that he transcribe a petition for them. They were concerned that American buffalo hunters were devastating the herds. These hunters acted illegally and the Kiowa petitioners implored the federal government to stop them. In the petition, they claimed that Kiowas and the buffalo had been created together, to be like brothers. They argued that one could not live without the other. If the U.S. government failed to protect the herds, Kiowas would also die.

While Native claims about relations to other-than-human beings were hardly uncommon, the Quaker employee had no reference point for understanding such connections. But unlike dismissive attitudes he displayed earlier in his tenure, the Quaker seemed open to seeing something new. In his account of the proceedings, he referred to the “gravity” and “reverential feeling” of the smoking session held prior to the discussion. In a letter, he encouraged federal officials to act because the buffalo were a “matter involving [Kiowas’] traditional religious belief.” For years, this Quaker worker had witnessed Kiowa buffalo hunting, as well as their use of hides for tipis and meat for food. He had observed, and even sent troops to monitor, Kiowa Sun Dances, rites in which the people gave thanks for the buffalo. After these experiences, he eventually saw something “religious” where he had once seen only heathenish practices unworthy of the descriptor.

Similar to the Quaker’s change in perspective, American expansion shaped Kiowa ritual life. Around the same time as the buffalo petition, Kiowas struggled to maintain practices that had been central to them for generations. They held Sun Dances in summer, even as hunger beset them and federal officials sent troops to monitor them. Along with efforts to sustain older practices, Kiowas also considered new ritual options. While men who raided south into Texas and Mexico had long encountered Native peoples who engaged peyote as a source of sacred power, Kiowas had never adopted it as a regular practice. That changed in the 1870s. With their Sun Dances under scrutiny and people suffering from outbreaks of disease, Kiowas gathered for peyote meetings. Welcoming ritual specialists from other Indian nations, Kiowas brought the rites to the reservation and developed their own practices and songs. Within two decades, peyote practices were widespread among Kiowas.

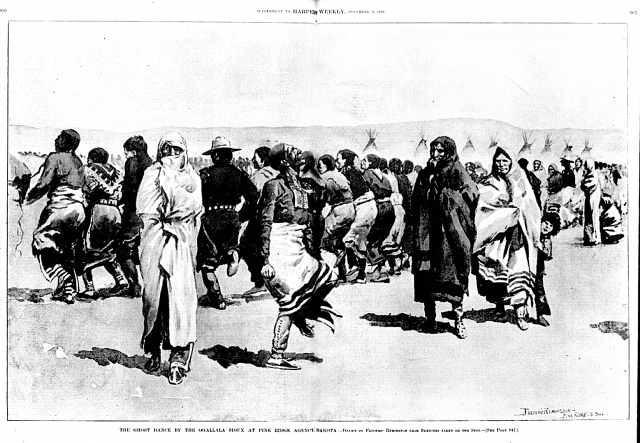

The Ghost Dance of 1889-1891 by the Oglala Lakota at Pine Ridge. Illustration by Frederic Remington, 1890.

Eventually, Kiowas would consider two more ritual options from outside their own traditions. In the 1880s, the first Christian missionary arrived. Under the tutelage of a Kiowa man who studied in the East and received Episcopal deacon’s orders, a small number of Kiowas accepted baptism in the early 1880s. Affiliation with Christianity increased after a host of missionaries arrived in the 1890s. Around the same time, messages from Native neighbors told of a Paiute prophet who claimed the world could be renewed through dance. Called the Ghost Dance by Americans, the movement spread to reservations across the West. Kiowas adapted it their situation, using feathers to identify the movement, singing songs and dancing with the hope of restoring depleted buffalo herds and returning loved ones lost to hunger and disease. By 1890, Kiowas participated in older Sun Dance and healing practices, as well as peyote rites, Christian worship, and Ghost Dancing, all in the hope of sustaining their lands and people threatened by American occupation.

William Warren Sweet wrote that there was no more influential “fact” in the development of American religion than “continuous contact with frontier conditions and frontier needs.” No historian working today would make such grand claims. Events on the “frontier” must be considered in relation to American efforts to reconstruct the South, debates about Chinese immigration in California, labor disputes and unrest in the North, and legal conflicts over Mormon plural marriage and what constituted acceptable religious practice. Even so, encounters prompted by expansion played a significant role in reshaping the religious worlds of settlers and Native people. It lay at the heart of settler ideas about American civilization and it functioned as one more resource in the struggle for Native peoplehood, lands, and sovereignty.

Jennifer Graber, The Gods of Indian Country: Religion and the Struggle for the American West

and more on the book here.

Further reading:

Richard Callahan, Jr. ed., New Territories, New Perspectives: The Religious Impact of the Louisiana Purchase (2008).

This edited volume looks at cultural and religious legacies of the Louisiana Purchase.

David Chidester, Savage Systems: Colonialism and Comparative Religion in Southern Africa (1996).

This study traces British explorers and merchants’ changing use of the category “religion” to describe, evaluate, and regulate indigenous populations in southern Africa.

Candace S, Greene, One Hundred Summers: A Kiowa Calendar Record (2009).

This book provides a helpful introduction to Kiowa history and culture, as well as Kiowa practices of historical memory.

Pekka Hamalainen, The Comanche Empire (2009).

This award-winning book details the rise and fall of the Comanche nation, an important ally to Kiowas in the nineteenth century.

Thomas D. Hamm, The Transformation of American Quakerism: Orthodox Friends, 1800-1907 (1988).

This study details changes in the Society of Friends, especially those that resulted from westward migration and settlement.

Louis S. Warren, God’s Red Son: The Ghost Dance Religion and the Making of Modern America (2017).

This popular book provides a big-picture narration of the many Native movements that comprised the Ghost Dance. It also posits how American identification of the dance as anti-modern fueled and provided justification for violent suppression of Plains Indian nations.